![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

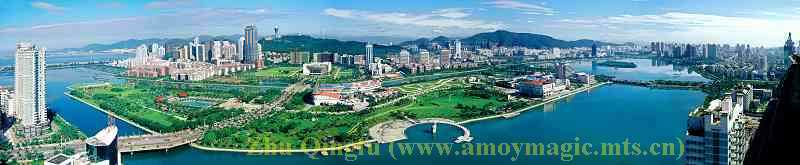

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

| Chapt.

1 Eastward Ho! Chapt. 2 Chinchew 600 Years Ago |

Chapt.5

Chinchew Houses & Temples Mosque Chapt. 6 Mandarins & Illuminati |

Chapt.7

Chinchew City Wall Chapt.8 First Things First |

Scanned by Dr. Bill Brown

( please use freely, but acknowledge Amoy Magic

as source--or link! Thanks!)

please use freely, but acknowledge Amoy Magic

as source--or link! Thanks!) Click

thumbnails on this page for larger images

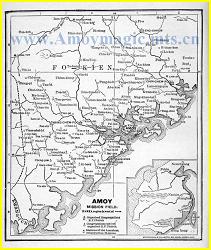

![Fújiàn Fukien Fokyen Ka-ho-san, Chuan-chhu-oa Foochow Big-Hat Toa-bo a mountain about 2,000 feet high within 25 miles of Amoy Su-beng-su Ko-koa (??) [Gaoqi [Gaoqi--site of Gaoqi International Airport, a small town about three miles northwest from Amoy." Lam-tai-bu Changchow [Zhangzhou] Chiang-Chiu Chang-chow and Chuan-chow Zhangpu Ka-ho-san huan-chhu-oa (outskirts of Amoy in hills) The Po-lam Bridge Loh-iu Luoyang ?? Chhah Siang ? Huì’an Pu-Nan Pho-Lam ?? 30 miles upriver from Amoy Chiang Kai-Shek. Chee-ang Khy-sheck Jiang Jieshi DELL ?? Metro ??? ??? Wal-mart](image003.gif) Click

Here to View or Download Biography of Jessie M. Johnston, Missionary

to Amoy for 18 years (1885-1904)

Click

Here to View or Download Biography of Jessie M. Johnston, Missionary

to Amoy for 18 years (1885-1904)

![Fújiàn Fukien Fokyen Ka-ho-san, Chuan-chhu-oa Foochow Big-Hat Toa-bo a mountain about 2,000 feet high within 25 miles of Amoy Su-beng-su Ko-koa (??) [Gaoqi [Gaoqi--site of Gaoqi International Airport, a small town about three miles northwest from Amoy." Lam-tai-bu Changchow [Zhangzhou] Chiang-Chiu Chang-chow and Chuan-chow Zhangpu Ka-ho-san huan-chhu-oa (outskirts of Amoy in hills) The Po-lam Bridge Loh-iu Luoyang ?? Chhah Siang ? Huì’an Pu-Nan Pho-Lam ?? 30 miles upriver from Amoy Chiang Kai-Shek. Chee-ang Khy-sheck Jiang Jieshi DELL ?? Metro ??? ??? Wal-mart](image003.gif) Click

Here to View or Download Biography of Caldwell Family (in Fujian from

1899 to 1949)

Click

Here to View or Download Biography of Caldwell Family (in Fujian from

1899 to 1949)

![Fújiàn Fukien Fokyen Ka-ho-san, Chuan-chhu-oa Foochow Big-Hat Toa-bo a mountain about 2,000 feet high within 25 miles of Amoy Su-beng-su Ko-koa (??) [Gaoqi [Gaoqi--site of Gaoqi International Airport, a small town about three miles northwest from Amoy." Lam-tai-bu Changchow [Zhangzhou] Chiang-Chiu Chang-chow and Chuan-chow Zhangpu Ka-ho-san huan-chhu-oa (outskirts of Amoy in hills) The Po-lam Bridge Loh-iu Luoyang ?? Chhah Siang ? Huì’an Pu-Nan Pho-Lam ?? 30 miles upriver from Amoy Chiang Kai-Shek. Chee-ang Khy-sheck Jiang Jieshi DELL ?? Metro ??? ??? Wal-mart](image003.gif) Click Here

for "The Life of Christ by Chinese Artists!" (1940)

Click Here

for "The Life of Christ by Chinese Artists!" (1940)

Scanned by Dr. Bill Brown (

please use freely, but acknowledge Amoy Magic

as source--or link! Thanks!)

please use freely, but acknowledge Amoy Magic

as source--or link! Thanks!)

THE city of Chinchew, in South China, lies a short distance inland from

the port of Amoy, opposite the north corner of Formosa. It is about the

size of Edinburgh, and, like Edinburgh, is devoted to learning, if the

product of Chinese mental activity may be so described. The graduates

who have taken their second examination there and gone on to Pekin for

their third examination, which entitles them to a place in the Government,

have been men of mark. In the Temple of Confucius there is a Hall hung

with tablets given to illustrious Chinchew men by the Emperor, which is

the pride of the city.

The story of the growth of a Christian community in that city, so as to

become a recognised factor in its life, is so noteworthy and told so well

in the following pages, that a note of commendation is hardly called for.

The story of the growth of a Christian community in that city, so as to

become a recognised factor in its life, is so noteworthy and told so well

in the following pages, that a note of commendation is hardly called for.

I am glad, however, of this opportunity of recommending this book to the

many Sabbath Schools north of the Border who are interested in Miss Duncan's

work. They have held the ropes while their missionary has ventured into

this unknown sea. A. H. F. BARBOUR. EDINBURGH, October 1902.

THE CITY OF SPRINGS

CHAPTER I EASTWARD Ho!

NORTHWARDS, they say, lies the magnetic pole; but for how many of Britain's

children does the spirit-compelling magnet lie, not northward, hut eastward,

ever eastward t The spell of the Thousand And One Nights is still on us;

tales of Xanadu, with "stately pleasure-dome," still possess

us; creeds framed ages back by hoary Chinese sages command our reverence;

let us but catch a glimpse of the inscrutable face of Buddha the impassive,

and we too are devotees, longing for Nirvana. So, at one time or another,

does the vision of the "Gorgeous East" hold our spirits in thrall.

Back to Top Amoy

Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

"We grow older, and the glamour of an Eastern past fails before the

light of our practical "Western today. Another and a truer vision

now rises on us. To one here and another there is given to see, not the

East of the Past, but a modern East; stripped of her gilding, with charm

stolen away; sunny Asia black with the plague-spots of heathenism.

Instead of a mighty rolling Ganges we see now the crowds of dusky men

and women vainly seeking salvation in its waters. Those picturesque palm-trees

that fascinated us once screen thousands of idol-temples round whose images

of wood and plaster, of stone and precious metal, rise the "vain

repetitions of the heathen." Buddha, displaced in India, broods grand

and unavailing as ever in his new Japanese garden shrine at Kamakura.

How the hitter wail of a helpless and

a modern Empress-Dowager guilty of the blood of the martyrs, and forced

to fly before the avengers as they neared the walls of Pekin.

Tales of Eastern princesses resolve themselves into the wail of wronged

and hopeless womanhood and childhood. British rule has indeed suppressed

the horrors of Suttee and Juggernaut, but still the terrible patience

of millions of purdah-hidden lives cries to us. Little children in China

still sob in agony over their cruelly mutilated feet; and from baby-tower

and baby-pit alike a terrible "Inasmuch as ye did it not" is

written over against Christendom.

This is the second vision which comes to some of us; and when, with the

vision, there rings in the ears the Great Command, "Go ye into all

the world and preach the gospel," then the East has indeed claimed

us for herself, and one more missionary of the Cross is enrolled.

Of all the countries of Asia, China, the land of Sinim, the Middle Kingdom,

is the chosen field. At the outset the would-be missionary has to face

the unknown in the shape of Mission Councils and Executive Committees.

After much trepidation of spirit we learn that we have been passed from

the category of candidate to that of accepted missionary, with "be

ready to sail in autumn " as our first order.

The getting-ready process centres round the mysteries of an outfit list.

Before this list has heen realised, i.e. stowed in concrete form inside

a number of packing-cases, we begin to understand that we are preparing

for a seven years' stay in a country whose climate is very unlike our

own. These last weeks fly past all too quickly. Then comes one morning,

the last, when the packing is quite done, and Fate, in the shape of a

prosaic old four-wheeler, waits at the door.

Grey mists hang over the Northern Capital, where friends wait to wish

us "God-speed." We take a last look at the monument, and at

the old castle glooming half-hidden above us. All too soon Auld Reekie

lies behind us, and we are "ower the border and awa'" in good

earnest. We awake next morning to find ourselves in London.

Have you ever attended a missionary valedictory meeting? On the platform

is ranged the missionary party, its raw recruits side by side with veteran

workers. One address follows another, and prayers rise that this little

detachment of the great missionary army may fight the good fight, and

wrest many captives from the arch-enemy. We join with something of a thrill

in the dear old hymns, "0 God of Bethel," and " From Greenland's

Icy Mountains "; but it is the full strain of "Jesus shall reign

where'er the sun Doth his successive journeys run," that suddenly

lifts us all from our narrowing .selfishness, and makes the audience one

in spirit with the pathetically inadequate little company up there on

the platform.

The meeting is over; but for us the next few days are one prolonged "valedictory,"

which only ends when the launch, our last link with the home-country,

steams steadily back to London Town. It is a very forlorn and insignificant

unit that is left behind on the deck of an ocean-going steamer.

Six weeks are ahead of us-six weeks to forget in, to learn in, and, above

all, six weeks in which to take in new impressions. Surely no one can

ever forget his first contact with the East. The gleaming white teeth

of that rascally black donkey-boy in Port Said; the first attempt to bargain

with an Oriental, when we were royally cheated by that smooth-tongued

charmer; the sense of boundless space, as day in day out the rhythmical

beat of the engine marks our steady progress eastwards across the Indian

Ocean; the idleness of long days of heat; the varying moods of sea and

sky; the rich glory that makes a sacrament of the sunset hour; and those

stars, surely never the same as our cold northern friends !

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

Such are some of the first voyage impressions which are with us to this

hour. Then, as at last we touch our most southerly limit at tropical Singapore,

there stands John Chinaman himself, gowned and pigtailed as we had heard,

but never till that moment realised. From there, as we face northwards,

and pitch and roll through all that wicked China Sea, if we are ever allowed

one lucid interval, it is to China, rather than to the home-land, that

our thoughts now turn. At last we are actually at peace, anchored in the

magnificent harbour of Hong-kong, and inclined to hold our heads just

a trifle higher, as we realise that it was British energy that transformed

that bare rock into this port of the East.

Only a couple of days more of coast sailing and we arrive. This is, perhaps,

the most curious sensation of all. We decided to go to China; we have

come all the long way out to China, and now we are here!

This

is Amoy harbour; that is the little island of Kolong-su, and

beyond is the mysterious mainland of China. These men in sampans,1 pushing,

scrambling, and yelling, are all Chinese, and those uncouth sounds belong

to their language, which, in a misguided hour, we had thought we might

aspire to learn. These men, in fact, belong to the great class of "heathen"

whom we have come all this way to try and teach. If ever human being feels

like an infant, ignorant and helpless, surely it is the poor little newly

arrived missionary, who takes in with all her five senses at once the

overwhelming fact of the absolute pole-apartness in looks, speech, habits,

thoughts, and everything else of John Bull and John Chinaman.

This

is Amoy harbour; that is the little island of Kolong-su, and

beyond is the mysterious mainland of China. These men in sampans,1 pushing,

scrambling, and yelling, are all Chinese, and those uncouth sounds belong

to their language, which, in a misguided hour, we had thought we might

aspire to learn. These men, in fact, belong to the great class of "heathen"

whom we have come all this way to try and teach. If ever human being feels

like an infant, ignorant and helpless, surely it is the poor little newly

arrived missionary, who takes in with all her five senses at once the

overwhelming fact of the absolute pole-apartness in looks, speech, habits,

thoughts, and everything else of John Bull and John Chinaman.

A warm welcome awaits us from missionaries who mercifully still remember

their mother-tongue, and who appear all to have survived the process of

"learning the language." A few days, and the neophyte may be

found armed with a copy of the famous "Douglas Dictionary,"

and if inspired with a boundless enthusiasm, is steadily massacring every

one of the seven distinct tones of the Amoy dialect, and this in an honest

if vain endeavour to imitate the sounds produced by that most long-suffering

of mortals, a Chinese teacher.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

CHAPTER II CHINCHEW

SIX HUNDRED YEARS AGO

THE name Chinchew, now so familiar to us, is merely an anglicised form

of Tsuien-chow, being the northern or mandarin pronunciation of the name.

In the Amoy language it is pronounced Tsoan-chiu. Tsoan-spring or fountain,

and chin-a city whose resident mandarin ranks as a prefect. The whole

may be translated City of Springs.

Chinchew has probably an interesting history dating back many hundreds

of years; only, like most things in China, it is difficult to get at the

exact truth about it.

Before describing the city as we in those latter days found it, it may

be of interest to know what Marco  Polo,

the great Venetian traveller, wrote of it so far back as the thirteenth

century.

Polo,

the great Venetian traveller, wrote of it so far back as the thirteenth

century.

The following description (taken from his records) may seem a little wonderful,

especially in the matter of the enormous trade with India; yet we must

remember that it is only within the last half-century that steam has killed

the trade of those large ocean-going junks. Also, as we see to-day, flat-bottomed

boats can enter a channel of very limited depth. Another possibility is

that the bed of the Chinchew, River may, in the intervening six centuries,

have become silted up, rendering it less navigable now than formerly.

"Now this city of Fugu" (identified as our Chinchew of to-day)

"is the key of the division which is called Chonka, and which is

one of the nine great divisions of Manzi.1 The city is a seat of trade

and great manufactures. The people are idolaters and subject to the great

Khan (Kublai Khan). A large garrison is maintained there by that prince

to keep the kingdom in peace and subjection; for the city is one which

is apt to revolt on very slight provocation. There flows through the middle

of this city a great river, which is about a mile in width, and many ships

are built at the city which are launched upon this river.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

Enormous quantities of sugar are made there, and there is a great traffic

about the isles of the Indies; for this city is, you see, in the vicinity

of the ocean port of Zayton. The vessels pass on to the city of Fugu by

the river "(i.e. the estuary of the Chinchew River)" I have

told you of, and 'tis in this way that the precious wares of India come

hither. The people have abundance of all things necessary for subsistence;

fine gardens with good fruit; and the city is wonderfully well ordered

in all respects."

Marco's Venetian contemporaries frankly discredited his tales, but those

Jesuits who visited China later on  confirmed

the truth of what he had written.

confirmed

the truth of what he had written.

"In this province there is a town called Izungu, where they make

vessels of porcelain of all sizes, the finest that can be imagined. They

make it nowhere but in that city; it is abundant, and very cheap.

"The process is as follows:-Collect earth as from a mine, and laying

it in a great heap, suffer it to be exposed to the wind, rain, and sun

for thirty and forty years, during which time it is never disturbed. Thus

it becomes refined and fit for being wrought into the vessels. Suitable

colours are then laid on, and the ware is afterwards baked in ovens and

furnaces. Thus it is collected for children and grandchildren. You may

there have eight dishes for one Venetian groat."

Fine porcelain is made to this day in Foh-Kien, and the details of the

process correspond to this description. One of his notes on Manzi is rather

startling. He says of one of its cities: "I was told, but saw them

not, that they have hens without feathers, hairy like cats, which yet

lay eggs and are good to eat. Here are many lions, which make the way

very dangerous."

We might with his contemporaries have been inclined to question the veracity

of Marco or of his informants had we not ourselves gazed with astonishment

on the quaint-looking fowls to which he refers. The cat fur, however,

proves on nearer inspection to be simply an abundant crop of soft, downy-looking

feathers. They are certainly proper fowls, only they are a sort of big-baby

kind, the adults still wearing the fluffy down of their unfledged days,

and somehow never attaining to the dignity of a quill. If they resemble

any cat it must be the fleecy Persian. As to the "many lions,"

he is quite right, except that they are not lions, but tigers 1 By some

curious error he always confuses the two. Presumably he had never seen

a menagerie. The Polos left Venice when Marco was only nineteen years

of age, and did not return from the court of the Grand Khan for twenty-six

years, so it is small wonder if the traveller occasionally confused Tartar

and Italian, and called things by their wrong names.

Back to

Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

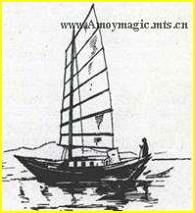

LEAVING the end of the thirteenth for the beginning of the twentieth century, let us follow the ordinary route from Amoy to Chinchew.

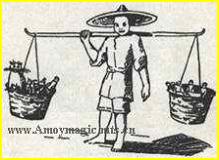

The great city lies between fifty and sixty miles in a north-easterly direction from Amoy, yet to reach it two days are usually required. The first day's journey is by junk (or latterly by steam launch) and takes us as far as An-hai. The remaining twenty miles of land journey are covered next day in six to seven hours by sedan chair.

We pass through a bare, uninviting stretch of country, broken by one or two slight hills. The main road, for this is part of the great mandarin road which runs from Pekin to Canton, degenerates at times into an untidy track. At one point it crosses a small stream by means of a log, chained at one end to prevent its being carried off in time of flood; and at another it meanders helplessly up and down a stone staircase leading over a little bit of a hill; but finally it becomes a purpose-like embankment stretching across a rice-plain, paved in places with lengths of substantial granite.

Streams of burden-bearers-"coolies"-pass up and down this narrow highway. The loads, slung to the ends of their carrying-poles, show an endless variety of merchandise. Huge crates of earthenware pots, bundles of native tobacco-leaf, bags of rice, heavy jars of sugar-cane juice, great wicker cages teeming with tiny ducklings, dried grass for fuel done up in loads about the size of small haystacks, baskets of sweet potatoes, taro and vegetables of many kinds, a live black pig carried by two bearers, bales of cloth, of paper, of cotton-wool, etc. etc., all these are carried, not on carts or railway trucks, but by the very primitive carrying-pole balanced on long-suffering human shoulders.

Such, too, is our own position; for we are being borne along by two men, and as they carry us onwards we notice the front bearer every now and again shifting the cross-bar at the end of the long bamboo chair-poles to ease the pressure on neck and shoulders. Query: What will those men say to the inevitable railway train.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

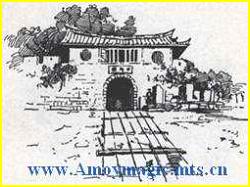

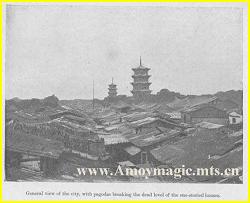

At last, far off, we see Chinchew; that is, we see a stretch of its high, battlemented wall, over which the tops of two great pagodas are clearly distinguishable, and behind which the houses of the city are quite hidden. Beyond, and to the west of the city, several high hills rise abruptly from the great rice plain.

As we approach, the villages grow larger, till, by and by, the road is lined continuously with market-stalls. Long before the great South Gate is reached, we have said good-bye to fresh air and free space, and have begun to make serious acquaintance with the various sights, sounds, and odours inseparable from a Chinese city.

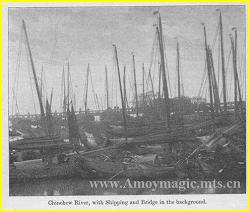

We cross the Chinchew River by a long, high bridge made of lengths of granite, resting on solid piers of the same. Its very open stone fence, adorned at intervals with grotesquely carved lions' heads, forms a rather inadequate-looking balustrade.

The river below seems fairly busy. A good many small junks, laden with lime, wood, etc., are coming down; while others, carrying salt, and various city-manufactured articles, are preparing for the more arduous up-stream journey. There are larger vessels, too,-fishing-boats from the coast, sea-going passenger-junks, and, farther down the river, large rice-junks. These all add to the bustle of the scene; and the clamour of voices from the jetties rises to us on the bridge in a confused babel.

On over the bridge, and past the Customs' barrier, we plunge again into the narrow, busy, close-smelling thoroughfare. Presently the way leads us under an archway, whose massive stonework and heavy gates remind one of some ancient "donjon keep." The uneven pavement leads on, with several characteristic twists and turns (these to circumvent the demons, who, it seems, require straight lines for their evil works), and we emerge again to find that we have been entering by the South Gate, and are now actually inside the great city of Chinchew.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

CHAPTER IV CHINCHEW-ITS STREETS AND SHOPS

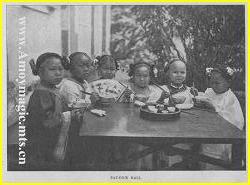

How describe a Chinese city to those who have never seen one? It is attempting the impossible. Photographs help home friends to realise things a little; but, on the other hand, they always do China an injustice, for they do not show up dirt and disrepair, two elements which are almost invariably present. Then the narrowness of the streets makes it difficult to focus a building. Good photos of street life in China are extremely rare, probably for this reason.

We would first ask the reader to try and dismiss from mind every idea of a home city. Thoughts of broad thoroughfares and the rattle of conveyances, side pavements with lamp-posts, tall houses on either side, and shops shining with plate-gJass windows,-all these must go, for Chinchew knows nothing of such. Instead, try to picture a city of single-storied houses, with streets not broader than our home side-pavements. In summer, large mats of woven grass or split bamboo, supported on bamboo rods stretched from roof to roof, keep off the burning sun. The result is a grateful shade; but also an atmosphere more exhausted and more actively " stuffy " than before.

Wheeled conveyances are here unknown, and the straw-sandaled feet of the burden-bearers pass quietly over the uneven flags. Noise there is in plenty, but not home-street noise. What we hear is literally the clamour of tongues. Bargaining accounts for most of the din. What looks to us to be a battle royal is merely a fairly amicable discussion over the price of some trifle; and possibly the sum of one cash is involved (500 cash = Is.). Had we time to wait, we should see the matter settled to the satisfaction of all parties; but our front bearer is shouting himself hoarse in his efforts to announce our sedan-chair. Chairs take precedence of foot-passengers and luggage-carriers in the streets; but they in turn have perforce to yield to an idol procession.

We feel quite certain at one moment that our chair is going to knock down half the people on the street, and hold our breath as some old man narrowly escapes a severe bump. Next minute we are waiting in a fascinated way the results of an impending collision with a stall that juts out farther than usual; but our bearers jog on ahead, apparently regardless of consequences, shouting constantly, "Lang-a lai-lai-lai!" ("People coming, coming, coming!"), and somehow nothing happens. Only once do we remember our chair giving a somewhat severe bump to a passer-by.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

City women, except a few very ancient ones, are conspicuous by their absence; but field women, who. live in the villages round about, may often be seen in the streets of Chinchew. These field women form a class by themselves, and are allowed a wonderful amount of freedom. They have natural feet; work in the fields, planting rice, etc.; and carry loads to and from the city, just like men. They certainly have a hard life; yet their strapping gait, their healthy, open faces, tanned with exposure to sun and weather, are in striking contrast to the pitiful, hobbling walk and the sallow, unhealthy complexions of their shut-in city sisters.

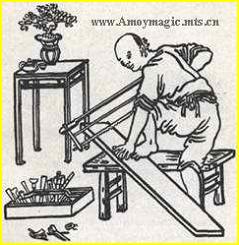

The shops on either side are full of interest. Perhaps one should say stalls, rather than shops, in many cases. When the shutter-boards are taken down in the morning, the shopkeeper puts out various trestles and boards, thus making increased surface for the display of his wares. Then, too, he must have his heavy wooden signboard in full view. All this encroaches seriously on the already too limited street space.

Some streets are given up to shops of one kind only. On entering the city the narrow street keeps at first by the wall, and here each shop shows pens, pens, pens. A little tuft of sable or of rabbits' hair, fixed in a bamboo tube, makes the brush-pen of China. Chinchew is a literary city, therefore pens galore. Here is Flower Lane, where every shop shows tinsel and silk artificial flower hair ornaments for women. Another street is given over to men's shoes. These shoes, along with the ordinary round, red-knobbed "bowl hats" worn everywhere, are two of the special exports of Chinchew.

On a little farther, where the street is wider, we find, amongst others, earthenware and china shops. Their goods overflow into the street. Never mind, there is still a clear passage in the middle, so the bowls, tea-cups, etc., are respected. Imagine the state of mind of a London policeman on such a street! As for a medical officer of health- but here imagination fails one.

There are cloth, silk, rice, basket, paper, and lantern shops. In the latter, you watch the workman covering little bamboo frames with paper, on which he paints the "character" of the god for whose shrine the lantern is destined.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

There are fruit-stalls where, amongst other fruits, bananas are sold for eleven out of every twelve months. There are huge pomelos (in structure, like oranges, but in size more approaching a moderate football), arbutus, dragon's-eye fruit, lychee, peaches (never properly ripened, and, as wo find, made a specialty of for keeping babies quiet in church !), lengths of sugar cane, tiny citrons and mandarin oranges, plums, persimmons, and many other fruits, known and unknown, all appearing in their season.

These are all nice, quiet, inoffensive shops. But oh, the frying apparatus doing its work in the street beside a refreshment shop!

Deadly looking messes frizzle noisily and odoriferously, and the whiff from the cauldron of seething fat, as it comes to a passer-by on a hot day, is a thing not easily forgotten.

Then there are the fish stalls, whence uncouth monsters of the deep grin at one. There are baskets piled with shrimps ; others with writhing crabs; there are whitish cuttlefish, exuding an inky-black fluid; while the narrow gray "ribbon-fish" show a perverted tendency to trail beyond the bounds of their baskets, and on to the street. Fishes, known and unknown, big and little, are there exposed for sale. In cold weather, the butchers and fish shops are quite passably nice, but hot weather can make them surprisingly haunting. Our hope in passing such was that this was not the shop patronised by our cook !

Many of the shops are such as could only be found in a heathen city. Wo see the workman, in full view of the public, carving out of a block of wood the image of the Goddess of Mercy, or some of their hundred odd deities; and this image, when finished, will be bought by some householder, that he and his may worship it. There are cheaper clay images, gaudily painted, and at prices to suit all purses.

A very large number of people are employed in connection with paper-shops, in making idolatrous paper-money, i.e. tissue" paper, with circles cut in it in imitation of coins, for use of the spirits in the graves. Once annually pious descendants visit their family graves, and strew an abundant supply of this mock "wherewithal" on the little mounds scattered everywhere in China. Then there is gold and silver paper-money, made of coarse yellowish paper, with a square inch of tinfoil in the centre, the "gold" being the same varnished over with yellow. This is for the spirits in the down-below regions, who receive this money by medium of fire, and so are provided with all the pocket-money necessary for their well-being.

Does everybody know that, a la Chinoise, the spirit of a man is threefold, and at death these three spirits find separate dwelling-places 1 One stays by the grave, another is banished to the infernal regions, and the third is politely housed in the little wooden "ancestral tablet" such as missionaries show at meetings. As each of these spirits requires attention, you will believe us when we tell you that the Chinese are a busy people. These attentions can be paid pretty cheaply, however, as paper-money is inexpensive. Also, spirits of children do not need any special care; and they believe that no woman, unless married and the mother of boys, has a spirit worth troubling about. So it comes that though some have triple honours paid them at and after death, yet many have none at all, thus evening up things somewhat.

This making of paper-money is light work, such as even frail people can easily manage. Many of the women who are now Christians, formerly made idolatrous paper, and one of the first claims the new religion made on them was to give up that by which they earned their daily bread.

The Chinese make all sorts of ornamental papers used as decorations at New Year time, generally with superstitious ideas attached. Shops and house-doors have those pasted on them to bring good luck and keep off evil spirits.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Candle, incense, and firework shops are also in the idolatrous category. Crackers are constantly fired off at all functions, but very specially at weddings round the bride's sedan-chair, to scare the evil spirits and bring good luck.

Three or four years ago, a characteristically Chinese episode occurred in the South Street, Chinchew. Someone fired off a string of crackers in the street, probably when a funeral or a red bridal-chair was passing. Some of these crackers jumped into a firework shop, and unfortunately set on fire some of the goods there. They in their turn began to fizzle and jump about, and crack and shoot and explode wildly in a deafening pandemonium. The fire spread to the shop next door-an oil shop, as it happened-and then followed a right royal blaze. Soon the shops on the opposite side caught fire too, and the flames were not got under till a considerable amount of property on both sides of the street was totally destroyed.

One of the burnt-out shops was rented by a Christian. He and his friends managed to remove the goods from their shops in time, but his wife's property, which consisted of some boxes of garments valued at one to two hundred dollars, was all burnt up. As we remember it, the woman bore her loss well, expressing thankfulness that no life had been lost. We realised in this incident the value of the injunction against the specially Eastern customs of laying up treasure on earth, but we nobly refrained from quoting it to her.

We had hoped that this disaster might prove a practical lesson to the Chinese as to the danger of leaving so little street space. We were disappointed to find the buildings rebuilt with the frontage even a little further forward than before.

The Christian family rented another shop farther down the street, this time one with fireproof stores built behind!

We must not forget to mention the opium dens. The uninitiated would pass easily without noticing them. The frontage is closed in and looks innocent enough ; only whiffs of the drug caught in passing suggest the proximity of those dens of vice.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

To speak of Chinese streets and to omit to tell of the dogs found therein would be a grave error. South China seems to know only one size of dog, a wolfish-looking creature, nearly as big as a collie. He may be black, or brown, or white and black, or a mixture of all. Some are well-to-do animals, with a home; others are wanderers, hungry and outcast. They are mangy, often hairless, decrepit-looking wrecks, that ought to be poisoned off quickly, only it is nobody's business to do the merciful deed. These latter are spiritless enough, but the house-dog justifies his office of watcher by barking at every stranger, and very specially at the "foreigner." It seems as if they always recognised the different sound made by our shoes on the stones, and each time they hear it, it comes to them as a challenge. They follow, barking and snapping, till one has passed their domain, and only cease their rather trying attentions when the next watcher along the street has been roused to a sense of his duties, and takes up the refrain. Some of the missionaries have to confess to feeling safer with a good stout umbrella in their hands at certain special street corners.

One of the dogs belonging to the missionaries disappeared suddenly and completely. Speaking with one of the men-servants about it, the missionary expressed a hope that the thief would at least treat the animal kindly. "Treat him kindly, indeed !" was the reply; "why, they have certainly eaten him up by this time, for he was young and plump." It was rather solemnising.

China has cats, mostly tethered, and gifted even beyond our home friends with the most heartrending and pitiful of wails. When asked why they kept the poor creatures tied up, they told us that without being tied up they would run away. Our pussy was evidently an exception to this rule. Other familiars on the street are hens, very often the fluffy white kind; also the inevitable and inimitable black pig. These hens make a living by their wits, it would seem, and arc often seen on the busiest thoroughfares scuttling hither and thither, always hopeful, but never attaining to much. Piggies, on the contrary, are fed regularly, and respond to the call of their owner with most unpiglike alacrity. These frequent the quieter and opener residential streets. Inside the courts of the houses, and also, I regret to say, inside the houses as well, both hens and pigs are constantly to the fore. Is anyone who reads this second cousin to the old lady who stopped her subscription to missions because missionaries ate fowls every day, while she could rarely afford one even for Sunday dinner 1 If so, we would fain invite the relative to "chicken" dinner in Chinchew. We believe that for smallness of stature and sheer muscular development, these wiry "chickens" of Chinchew are unsurpassed.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

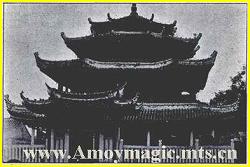

CHAPTER V CHINCHEW-ITS HOUSES AND TEMPLES

THERE is a general plan of the city which, if accurately carried out, would make its topography very simple. The great surrounding wall of the city is pierced in four places by gates known as the North, South, East, and West Gates. From these gates run four main streets, named respectively, the North, South, East, and West Streets. These converge towards the heart of the city, and form a cross at point of meeting. Spanning each of these four main thoroughfares, at a few minutes distance from the central cross, are high buildings like archways. These are called the Ko-lau, or Drum-towers, and are distinguished, as were the gates and streets, by calling them the North, South, East, and West Drum-towers. The square within these four towers is considered the heart of the city.

That sounds a simple enough plan; but, first, the walls do not lie four square, nor are those four gates equidistant. There are, in fact, three other gates, namely, the New, Water, and Mud Gates, and they too have streets named after them. The streets are never straight, but purposely winding-this also on account of the spirits,-and again they do not intersect exactly in the centre of the city, but nearer the North than the South Gate, thus making the "heart of the city" not at the exact centre. Add to the above the great similarity of the business thoroughfares, the countless number of narrow intersecting passages, the absence of any clearly printed street names, and it will be seen that it is fairly easy for strangers to lose their way in Chinchew. The most crowded part of the city is towards the South Gate. There is also a large population outside of it. Goods are pretty heavily taxed on entering the city; for this reason many evade the duties by doing their business just beyond city bounds.

The gates we have referred to above are always closed by about nine o'clock at night. The boom of a cannon announces the fact; and latecomers must all wait till sunrise next morning for admission, when another report proclaims them open.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Chinchew is not without its attempts at drainage. Under the uneven granite slabs which form the street pavement, there is a drain to carry off surface-water. The drains are seldom interfered with. It takes only a short spell of real rain-and it can rain properly and systematically in China !-to prove beyond contesting that these are hopelessly inadequate.

The North Street, just beyond the crossways, is, in the rainy season, in a chronic condition of being flooded. Often the schoolgirls bound for i he South Street Church have to wade at that place. Sometimes the way is quite impassable, and a separate service held in the school hall is the result. The doctor, who had at one time to pass up North Street on his way to hospital, suffered much inconvenience from this constant flooding. Seeing that a little rearranging of the drain would allow this standing water to run off quickly, he offered to benefit the whole neighbourhood by paying all expenses in connection with the alterations.

His

offer was politely but decidedly refused. It seemed that the changes would

involve the moving of some of the paving stones with which the " luck

" of that part was intimately connected. The whole community would

rather endure any amount of such minor inconvenience as flooding, than risk

the ill-will of spirits.

His

offer was politely but decidedly refused. It seemed that the changes would

involve the moving of some of the paving stones with which the " luck

" of that part was intimately connected. The whole community would

rather endure any amount of such minor inconvenience as flooding, than risk

the ill-will of spirits.We remember on one occasion walking to week-night prayer-meeting in the South Street Church when rain was just threatening. While in the meeting, the downpour came, the noise of it drowning the speaker's voice. At the close of the meeting wo were informed that the street was impassable, and we must wait till chairs could be procured for us. After some delay these were found, and we, sitting high and dry in our chairs, had a fine view of the scene. The streets were river-beds, and at the crossways, where a few stone steps lead up to the North Street, we were met by a roaring cascade. The bearers, with their short trousers tucked up as high as possible, and protected overhead by their most practical rain-hats, waded on slowly and carefully to avoid slipping, and deposited us safely at our own door.

It often happens in rains of this sort that the houses are flooded, and in specially great floods the streets may be quite impassable, except to a swimmer, or by means of a boat.

On one occasion a missionary coming down from Engchhun, found himself, boat and all, inside the city; nor could he tell us by which Gate he had entered, as the rice plain was- completely under water, and landmarks unrecognisable.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

There is also one great city ditch arranged on a system which would be excellent if it would only work. This great open channel begins outside the city wall by the river, and it runs in a bend through the city; then, piercing the city wall, it runs again to the river. The small drains under the streets are supposed to empty themselves into this ditch; and the ditch itself ought, twice a day, to be flushed by salt water at high tide. It usually happens, however, that the ditch is more or less choked, and if a mandarin wants a good excuse for extra taxation, he says he wishes to expend the money on clearing it out. This clearing process,

unfortunately,

he usually defers.

unfortunately,

he usually defers.We have said that the city consists of single-storied houses. To this again there are exceptions. The theory is that any building jutting out beyond the general level destroys the good Fungshui of the place.

There is, however, at least one private house in the city with an upper storey. The facts about it are instructive. A Chinchew man went abroad, probably to the Straits. There he made money, saw something of the modes of life of other peoples, and became more or less emancipated from the laws that obtain in his native city. Having " made his pile," he, like a true son of China, returned homewards again.

Once back in Chinchew, the desire seized him to build himself a fine house, and, very unwisely, he decided to defy the spirits and have it built with an upper storey. The house was finished with a good deal of fine woodwork and ornamental plaster decorations, and looked really well. Such defiance of use and wont, if it did not annoy the spirits of the air, certainly roused the spirits of the citizens of Chinchew. They did not pull down his house, but made a determined set on his purse by instigating one lawsuit after another against him. By the time the house was finished the poor man had not sufficient money left to live in it himself, but was forced to seek a tenant. Our medical missionary, happily, was able to rent it, and the cool open verandah of the upper storey has been a great boon to our mission staff.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

Then there are the four Drum-towers, and also the two great many-tiered East and West Pagodas. The latter are the most noticeable architectural features of the city. When they were built no one can tell. There they stand a little way back from the West Street, looking like great guardians on either side of a large Buddhist temple. These pagodas are supposed to be very specially connected with the luck of the city. Should anything happen to them a panic would certainly ensue.

As to temples, Chinchew has, of course, its full complement of these, and the images they enshrine compare favourably for sheer repulsive-ness with those of other places. The majority of the temples are Buddhist. The entrance courts have a certain grandeur about them,-but the interiors are tawdry and unlovely to a degree.

The great Confucian temple is dignified by contrast, its single tablets typifying the homage paid to the memory of the one great teacher seeming a noble conception in face of these temples full of gaudy, ungainly images.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

The Moslem Mosque Chinchew possesses the ruins of a rather remarkable building, namely, a Mohammedan temple. It must have been a handsome and outstanding structure in its day. The roof is now gone, and the walls are somewhat broken; while only the bases of the pillars remain; yet the dressed granite stones of the walls, with their Arabic inscriptions still legible on them, and the well-laid pavement of the main building, give some idea of the former solid proportions of the building. It probably dates back several centuries. Followers of Mohammed are chiefly found in Central and Northern China; and it is scarcely probable that many in Chinchew were ever really of Moslem faith. It is more likely that some powerful mandarin coming from the North-West Provinces settled in Chinchew, and built this mosque for his own family and retainers. The family has either left or died out; and now barely a dozen worshippers assemble on special feast-days in the poor little room rented by them beside the ruins of their former temple. The leader of the sect seems ignorant enough; and, though able to repeat passages from the Koran, was unable to explain them to us. One of the worshippers rents his house strictly on the understanding that his tenants do ' not keep pigs; and this same man spits conscientiously when he sees anyone eat pork!

Another trace of Mohammedanism is to be found in a village near Siong-see, where the people claim that their ancestors worshipped the God of the Christians. They really were Mohammedan at one time; now the only difference between them and the heathen round about is that they never offer pork to the spirits of the ancestors. The wave of Mohammedanism did indeed spread far and wide; but now only this stranded ruin and the pitiful handful of worshippers remain to show that the receding wave had actually touched the eastern confines of China.

The only other specially notable buildings of Chinchew are its Examination Halls, and the yamens of the various mandarins. One at least of the latter has good grounds attached.

Not many years ago, a head military mandarin of Chinchew, General Sun, determined to enjoy the pleasures of driving. Accordingly he had a short carriage drive constructed within his own grounds, and ordered a European-made carriage. He once invited some of the missionaries to his yamen, and treated them to a drive. One man stayed by each pony; and the spectacle of these men wildly encouraging their respective animals, and of "Jehu" driving furiously, was almost more than any Westerner could view without being hopelessly overcome by laughter.

This General Sun is the man who, while commanding the Chinese forces in Tam-sui (N. Formosa), held the French at bay, literally and metaphorically. He delighted to "fight his battles o'er again" in presence of an appreciative audience. According to his story, the poor French had not a quarter of a chance against him! He has gone now, and the carriage is no longer in evidence.

Inside the yamens there is space; and there might be dignity, only an unkept and uncomfortable air pervades everything. There is a want of freshness, neatness, and even cleanliness which no amount of grand dresses worn by the lords and ladies within can quite counteract.

Back to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen and Fujian

CHAPTER VI MANDARINS

AND LITERATI

ANY description of the city which, deals only with its business parts

must be incomplete, not to say misleading. While Chinchew is a large centre

for trade, it is also an important governmental centre; but its proudest

claim is being a literary city. They tell you, "Changchew for commerce,

but Chinchew for learning." Changchew is a large city inland from

Amoy.

The Chinese grade trades or professions thus:-1. The Literati; 2. Farmers;

3. Artisans; 4. Shopkeepers. This makes Chinchew rank three steps higher

than Changchew-in its own estimation!

The civil and military governors of the province have their headquarters

at Foochow. Chinchew ranks next as a prefectural city, and its prefect

has powers over a wide district. Various yamens, at once the residences

and court-houses of these rulers or mandarins, are scattered over different

parts of the city. There are always soldiers about, and their barracks

and parade-grounds are in the more open parts, between the North and East

Gates. There curious scenes, such as of warriors astride prancing ponies

shooting arrows wildly in the direction of paper targets, were till quite

recently the joy of the amazed Western beholder. Nowadays volley-firing

in the small hours of the morning seems to be absorbing their martial

energies, and it is an exercise rather disturbing lo the neighbourhood.

Then as to the literary claims of the city. All mandarins attain their

rank simply through competitive examinations. Their office is never hereditary.

There are in China an untold number of aspirants for office. These study

the works of Confucius, Mencius, and others, and come up periodically

for examination to the various centres. The mandarins in their turn are

the examiners. At Chinchew a good many degrees may be obtained, though

the highest must be sought by the student at Pekin.

Chinchew has annual examinations, but the great examinations fall due

only every second or third year. At such times students from far and near

flock into the city, as many as ten thousand of them. The streets are

then full of those curious anachronisms, men with their minds steeped

in the learning of twenty-five centuries ago, and who could not name over

the countries of Europe if their lives depended on it; men whose supercilious

stare-if they do condescend to look at one-is sufficient indication of

their attitude towards the mushroom foreigner.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

They form an imposing-looking set. The portentous strut, long robes of

delicately coloured silk (pale lavender predominating), the enormous spectacles,

the long pigtail undulating as he walks, the fan adorned with choice sayings

of the ancients, and the long bird-claw finger-nails much in evidence,

proving that their owner never did one stroke of honest manual labour;

all these, steeped in an atmosphere of intense self-conceit, go to the

make-up of that most bigoted of beings, the Chinese literatus.

These are the men who hate every innovation, and who have kept China standing

still. These are the men vho know by heart the moral maxims of Confucius,

while their vicious lives are in utter contradiction to his teaching.

And yet, remembering how "even in Sardis" some few had "worthy"

written over against them, we must not condemn those men root and branch.

Dr. Griffith John, writing of the Chinese crisis in 1900, says: "The

command had gone forth to massacre all foreigners and to annihilate the

Church, and but for such men as Liu Kunyi, Chang Chih-tung, and Tuan Fang,

it is almost certain that all the missionaries in the interior and all

the converts in the Empire would have perished."

Speaking more particularly of Chang Chih-tung, he says: "The love

of money does not seem to be in him." Another says of him : "This

man finds his ideal of human life in Confucianism; he is a true patriot

and an able statesman." There are, then, some few bright exceptions

to the above sweeping charges brought against the literati of China.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

CHAPTER

VII THE CITY WALL

BEFORE proceeding to trace the planting and development of the mission

in Chinchew, there is yet one physical feature of the city which claims

some special attention. Chinchew, like most Chinese cities, has its great

surrounding wall. This is a structure of solid masonwork about thirty

feet in height. Just outside of it there runs a moat in very incomplete

condition. This mild defence would not hinder an enemy for long; but the

solid face presented by the walls looks as if it would keep off any attacking

force that would conscientiously refrain from using dynamite.

The wall is kept in good repair. It is about ten feet wide on the top

at its narrowest parts, and is much wider in places.

Mounting by the stone staircases at any of the gates, we find ourselves

at once lifted to a purer atmosphere. There, if anywhere, even after the

hottest of days, there is a coolness which refreshes wonderfully after

the heavy tainted air of the city. Missionaries often walk here just after

sundown; and as the Chinese never think of "taking a walk" in

our sense of the word, they have the wall to themselves.

Only once do we remember seeing any considerable number of Chinese on

the wall. It was in a time of great flood, when water was about eight

feet deep in some of the houses outside the West Gate. There were people

huddled in a state of damp misery on their sloping tiled roof, while others

in boats were moving about carrying cooked rice, etc., to the unhappy

refugees. We found quite a farmyard establishment on the wall. Fowls,

goats, pigs, and cattle had been driven up there, and their owners were

beside them, waiting in dreary patience till the waters should subside.

On the wall, at intervals, are stray cannon. Probably there once was a

time when these were usable; but as they lie there dismantled on the stones

they reveal one of the causes why China fell such an easy prey to Japan.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

As we walk on we come to a great pit inside the wall itself. Look down

into it. There is not much to see; only some most pitiful little bundles

done up in matting. Do you realise what those are? Girl babies; only girls,

and so not wanted. Why have all the trouble and expense of bringing up

another girl when in the end she will marry into another household. She

is of no use in "building up" the family she was born into,

so the little mat-bundle is made up, carried to the wall-top, and dropped

into this silent, ghastly "baby-pit." Poor China, a country

where womanhood is not respected, nor child-life held sacred!

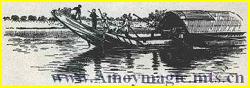

Looking outwards through the openings in the battlements we see the rice

plain, and have a capital view of the busy farmers, who raise two and

three crops from the same ground in one year. Sometimes the fields are

being flooded with water, and the penetrating creak, creak of the irrigator-worked

by a sort of treadmill contrivance-is over all the land. Only a few weeks

later and the startling sheer green of growing rice has hidden the water,

and again this gives place to the yellow of waving grain ready for the

sickle.

But it is inwards, to the city itself, that our eyes turn. Two things

that surprise one are, first, the amount of open unbuilt space between

the North and East Gates, where vegetable and chrysanthemum gardens prevail;

and, second, the number of fine old trees, notably banyan and dragon's-eye

fruit trees, one sees in parts. The banyans are usually inside the grounds

of a yamen, or beside a temple.

There below us lies the city. The undulating roofs of its single-storied

houses seem to us coterminous, so little break do the narrow intersecting

thoroughfares make.

These waved roofs are fascinating. Beneath them live some 300,000 people

bound soul and body by custom and superstition, and bitterly resenting

any interference with their bonds. One goes to heathen lands with strangely

erroneous ideas as to the heathen and their needs. The Chinese people

are not stretching out their hands for the gospel, they are more than

content with their own idolatries. They are not looking-consciously, at

least-for a Saviour, or greedily drinking in the message you send them.

The truth is, they despise the foreigner and all his ways, and they are

the most appallingly self-satisfied race under the sun.

And yet even here, amongst this people intent, like the man with the muck-rake,

on all that is low, vile, and worthless, whose highest ambitions are pitifully

low, some are found whom God has inspired to seek after, if haply they

may find Him. There have been men in Chinchew so in love with righteousness

and moral living that they of their own accord preached morality to their

fellows, and this before the gospel reached them. Here aud there we have

found heathen women practising a self-denial that would put us to shame;

and their reason for so doing was that they or their families might live

good and pure lives. Just one instance of this. The ancestral home of

a rather well-known priest is in the city, near the North Gate. This priest

was attracted by the gospel, and finally became a decided Christian. By

throwing up a lucrative profession he, of course, incurred the ill-will

of his relatives.  "While

he was still alive he had influence enough in the family to secure that

one or two of the children of the household should attend school, but

after his death these were withdrawn, and we seemed to have lost all touch

with the family.

"While

he was still alive he had influence enough in the family to secure that

one or two of the children of the household should attend school, but

after his death these were withdrawn, and we seemed to have lost all touch

with the family.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

As we were passing the house one day, we thought we might as well call

in and see if a renewed hearty invitation to church would meet with any

response. Instead of going to the main part of the house, we found ourselves

in a little back room, where a very old woman was sitting. She was, I

think, a sister-in-law of the former priest. We invited her to church

next "worship day."

"No, I am too old, and I do not know how to read."

We assured her that the Heavenly Father would not reject her because of

her age, and told her it did not matter at all about being able to read.

"I am too feeble; I could not walk all the way to church." She

had tightly-bound feet, and looked old and frail enough, so we told her

that God was everywhere-she could worship Him here.

"But I am a vegetarian," she said, coming at last to the real

reason. "Yes, for the last twenty-five years I have eaten only vegetable

food. It was not for myself I was doing it, though."

The usual idea in vegetarianism is that by a restricted diet the body

is purified, and merit accumulated, so that the spirit is made worthy

to become after death an object of worship, to become an idol-spirit,

in fact.

"No, it is not for myself I am doing this, it is for my son. I want

him to be good. I have commanded him to go to your church, and to worship

your God. If he worships God he will not eat opium and will be a good

man. I am going to give over all my twenty-five years' merit to him."

We suggested that she would surely like her spirit to be with his after

death. If her son worshipped God, he would go to be with Him. Would she

not like to go too!

"No, I must go on eating vegetables only for him, for I want him

to be a good man, and ho is to have all my merit."

She was old and frail, and confirmed in her idea. Her mind seemed incapable

of taking in a new thought. For all those long years she had lived her

life of self-denial for her son, and now nothing that we could say could

shake her belief in the efficacy of this transferred virtue. Evidently

the old priest-the one Christian she had known-had been a good man, and

his life had convinced her of the power of the God of the foreigners.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

Without any thought of self, she had done what her poor ignorant old mind--or was it heart!--suggested to her, and to us it seemed very beautiful indeed.

Weleft her quite untouched by our words, and probably she had died long ere now. A heathen woman who could love like that,--oh, the pity of it all! Why did we not send sooner to tell her of Him who is Love? Once again the old rock-text comes to us, and this time with a deepened meaning--"Shall not the God of all the earth do right?"

PART II MISSION WORK IN THE CITY

CHAPTER VIII FIRST THINGS

WHEN our Church sought to establish a mission in China, it sent as its

first missionary William Chalmers Burns. He left England in 1847, recommended

by the Church at home to choose Amoy as his headquarters. It was not till

1851, however, that Burns left Hong-kong and Canton, and actually settled

in Amoy. There he was joined by various other missionaries, ordained men

and medical men, and slowly the mission took definite shape. The work

took hold on the mainland at first in the Pechuia and Bay-pay districts,

to the south-west of Amoy. Later on a little, in 1857, a beginning was

made to the north-east, when Dr. Carstairs Douglas visited An-hai. In

1859, that station was definitely occupied. A glance at the map will show

that An-hai is a sort of half-way house to Chinchew, and such in effect

it has proved to be.

While

engaged in the work of opening this new centre, the missionary could not

but hear constantly of the great unknown city beyond. From dawn to dusk

the road stretching northwards showed its long narrow procession of blue-clad

carrier?, to whom " the city" was as the centre of the universe.

As he went about the markets and streets of An-hai preaching and teaching,

the quick ear of the man who was to compile our dictionary would soon

distinguish amid the babel the rapid utterance, modified vowels, and peculiar

accent which mark a Chinchew man. In his country work round An-hai, Dr.

(then Mr.) Carstairs Douglas could not but hear tales of the dark days

when some of the interminable village feuds, which are characteristic

of that turbulent district, roused the wrath of the city mandarin. Vengeance,

in Chinchew Plain, with "Dragon-Fountain Hill" in the distance

(see page 59) the shape of a body of soldiers, would be seen marching

down the long highway, and woe betide the hamlets where these settled

to dispense their summary justice!

Then, again, whether in town or village, everywhere he would meet with

some who wore the long robe of the student. To these men "the city,"

with its examination halls, was the beginning and end of existence. So

in countless ways the missionary would be led to turn longing eyes northward,

and the thought "the city for Christ" would take an ever deepening

hold on his mind and prayers.

Away back in the end of the fifties, one incident stands prominent, marking

the beginning of the work in Chiuchew. We of a later generation have heard

the story, and pictured it to ourselves so often that it almost seems

as if we had seen that little band of native Christians, led by Dr. Douglas,

kneeling there on the hilltop amongst the granite boulders. This story,

and the record of the first visits to Chinchew, had best be given in the

missionary's own words.

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

"On Monday last, 13th June (1859), I went, for the second time, to

a village four or five miles distant (from An-hai) in the direction of

Chinchew, called Leng-sui, i.e. ' Spiritual water.' After spending the

day preaching to the villagers under a large banyan tree, we returned

by way of a high hill, called the ' Dragon-Fountain Hill,' which rises

just above the village. Part of the ascent was in the chair which brought

me from An-hai, the upper part on foot. That view was most impressive.

The day being clear, we saw quite plainly the mountains of four departments

-Chinchew, Chang-chew, Hing-hwa, and Yung-chun. Of these, the two latter

have not yet heard the gospel at all.1 The plain around the hill is-as

we find everywhere-crowded with large villages; but, to my eye, the great

object of interest was the populous city of Chinchew, of which I had a

full view about ten miles distant. With a small telescope I saw clearly

one of its large bridges, and the two fine pagodas within the city. Before

descending, we knelt together on the summit of the hill, making supplication

for the wide region of darkness spread at our feet, and especially for

the city of Chinchew, whose sole specimen of Christianity consists of

the two opium ships moored at the mouth of the harbour. Alas, that it

should still bo true that the children of this world are wiser in their

generation than the children of light, wiser and more zealous too! Pray

ye, therefore, the Lord of the harvest, that He may send forth labourers

into His harvest."

[1"Hing-lioa" is now occupied by the missionaries of the

C.M.8. and of the American K. Moth. S; while " Yung-chun" is

our own Eng-chhun.]

CHAPTER IX EARLIEST

VISITS TO THE CITY

IN the end of the same year (1859), and again in December 1860, Dr. Douglas

paid his first two visits to Chinchew.

So far as is known, only one missionary had previously visited the city.

That was some three years earlier, when a British consul, accompanied

by Dr. Talmage, of Amoy (American Presbyterian Mission), passed through

it.

Dr. Douglas moved about the city, visited the various public buildings,

and preached a number of times with surprising freedom from molestation.

He noted at once as the two characteristics of the people superstition

and pride in their learning. Commenting on this pride, he writes: "The

city has produced many distinguished men, the latest, Hwang Tsung Han,

who succeeded Yeh as Governor-General of Canton. I saw yesterday a tablet

erected to him a few years ago in the Confucian temple here; his elder

brother still lives in the city as the head of its literati."

One note is very prominent in the earlier letters, and that is bitter

regret that the heralds of the gospel should have been forestalled in

this, as in so many- other places, by the opium-dealer.

On the second visit Dr. Douglas was accompanied by the Rev. H. L. Mackenzie.

On their arrival they found a freshly pasted-up copy of the Ten Commandments

just at the South Gate, a happy augury for their work there.

Strangely enough, most of their preaching was done at the mosque, to which

we have already referred. Dr, Douglas writes: " One day we preached

in the street opposite its door, and on another occasion within its ruined

walls. I should scarcely say ruined, for, though it has evidently been

long roofless, the walls of the mosque are in excellent preservation.

It is some sixty or seventy feet square, built of good granite; the bases

of the internal pillars still remain. It was a scene calling up a crowd

of strange associations; to stand, in the midst of a great heathen city,

on a broken pedestal, within the roofless mosque, preaching the gospel

to a crowd of Confucians, Mohammedans, and Buddhists; while those walls,

covered with Arabic inscriptions, which had so of ten "resounded

to the words of the Koran, now echoed the name of Jesus, the only-begotten

Son of God. The Moslems were a witness to the heathen that there is only

one God, and that the idols are vanities; but they seem to have quite

forgot their own worship, except that in some measure they reverence one

day in seven, and-if we understood them' right-that they offer a burnt

sacrifice once a year."

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

His prayer for Chinchew is: "Oh that we may be permitted to prepare

the way of the Lord, and make straight His paths in this city of three

or four hundred thousand inhabitants!"

Since his two first visits to Chinchew recorded above, Dr. Douglas had

wished much to have a station opened there, but the work was spreading

rapidly to the south-west of Amoy and absorbed the missionaries' energies.

In the meantime the little much-persecuted congregation at An-hai, with

its twenty-four members, had been doing its utmost to spread the knowledge

of the gospel in its own district. When its membership had increased to

thirty-two, this brave little congregation thought it should now be attempting

greater things, and so consulted Dr. Douglas as to the advisability of

taking up Chinchew as its mission-field. Dr. Douglas went north again

with two native agents, and found no difficulty in renting rooms suitable

to serve for a small preaching hall. These were situated in the very heart

of the city, and close to the great thoroughfare of the South Street.

The two native helpers remained in the newly-rented premises, and thus

was made a first beginning towards the permanent occupation of the city.

The Rev. W. S. Swanson in I860, and the Rev. W. M'Gregor in 1864, came

to Dr. Douglas' assistance. In 1866 we find Mr. M'Gregor writing: "The

Foo city of Chinchew we now number among our regular stations."

We, who have known only the Chinchew of to-day, can scarcely realise what

it must have meant for those pioneers to visit the city as they did from

time to time. There was not one Christian there to welcome them. As foreigners,

they would be objects of the greatest curiosity. Out of doors, wherever

they went, they would be practically mobbed; while even in their lodgings

privacy and quiet would be out of the question.

Their "Amoy," fluent as it might be, would sound barbarous in

the ears of those northerners.

More preposterous even than the appearance and tongue of the foreigners

would be the message they brought. Imagine a Chinaman standing on the

steps of St. Paul's proclaiming with passionate earnestness, in broken

English, the doctrines of Confucius. Think for a moment of the chaffing,

jeering crowd around him, of the sheer amusement his unthinkable conceit

and audacity would create. Would any single man in the millions of London

dream of taking him seriously 1 Hear him tell how for over 2000 years

the name of Confucius has been the most honoured in the far East, and

how to-day 400,000,000 Chinese acclaim him the great teacher, and profess

to shape their lives by his teaching. How would such statements affect

the Londoner! Let him go on to expound one of the best moral maxims of

the Chinese sage, and for how many minutes would they give him a hearing!

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

Or take Edinburgh, a city famed, like Chinchew, as a centre of learning,

and with much the same population. Picture to yourself two or three misguided

Chinamen standing at the gates of the University, ready with basket-loads

of tracts which explain the merits of the teachings and person of Confucius.

How many of our Edinburgh students would receive such tracts at their

hands ? How many, if they did accept them, would really study them afterwards

? What chance would those Chinamen have of making one convert ?

You think the cases are not equal, but they are, and far more so than

you would believe. We speak of our Western civilisation, and of ourselves

as "the heir of all the ages," but has not the Chinaman more

of a past than we have, and has he not been civilised long before we were

a people ? Do we call it arrant folly and impertinence for a Chinaman

to preach to us t In just such a light does the literatus of China consider

our interference. Are we sure that we have the truth for ourselves and

for all the world besides ? No less certain is our long-gowned friend

that he alone knows anything at all. The only difference between us is

that we want to convert him to our way of thinking, while he is in the

more dignified attitude of keeping himself to himself.

What, then, is our warrant for interfering with this ancient and civilised

people? Why, when we know that we would never tolerate a Chinaman's preaching

Confucius to us, do we offer him tracts, and expect him to listen to our

preaching of Christ? The only answer is that Confucius and his vows are

dead and powerless, while we preach One who "ever liveth," whose

words are "quick and powerful"; One whose last command was,

" Go ye therefore and teach all nations," and who, when He revealed

Himself again to His beloved disciple, said, ''And let him that heareth

say, Come."

It was a noble order, inaugurated by St. Paul, that of "fools for

Christ's Sake." Those who, in the early days, faced the wise men

of Chinchew, and told them in imperfect Chinese of the One greater than

Confucius, even Christ, these men have earned their fellowship with the

Apostle of the Gentiles in this holy "order"!

Back

to Top Amoy Magic Guide to Xiamen

and Fujian

CHAPTER X "FIRST

THE BLADE"

IN the early days any visits made by the foreign missionary to Chinchew

would be short, and at very infrequent intervals. Much of his time had

to be occupied with business matters connected with the renting of chapel

premises. While his appearance attracted crowds, making him perforce act

as a capital walking advertisement of the gospel, still it was only a

few days at best that he could give to the work of preaching. Such fragmentary

efforts could not, of course, build up a church. To the native preachers,

and very largely to the lay helpers from An-hai, belonged the privilege

of gathering in the first converts in Chinchew.

We can in a sense share the joys and the hopes of the pioneer foreign

missionary, but it requires more effort to put ourselves in the place

of these faithful native helpers. Themselves but "babes in Christ,"

it would be with sinking hearts that they escorted the missionary through

the South Gate, bade him a reluctant "good-bye," and turned

to face, with what courage they could muster, the formidable task of holding

the fort there in the very stronghold of the enemy.

Theirs was no easy task. To the foreigner a certain amount of outward

deference would be paid; but the message on the lips of those who were

unlearned and ignorant men would meet with scant ceremony. They would

be taunted with "eating" (i.e. making a living off) "the

foreign doctrine," and with joining a sect that had "neither

father nor mother," the latter being a cutting reference to their

having ceased to worship their ancestors. So long as they were few in

number, the literati would ignore them; but let them have any slight measure

of success, and these would surely stir up trouble.

Day after day these workers proclaimed the gospel, in season and out of

season; wherever and whenever they could get a hearing they told out the

"old, old story"; and, in the telling, it became more real to

themselves.

Sunday would be their brightest day, for one or two of the An-hai brethren

spent many a week-end in the city, willingly walking the twenty miles

there and back that they might help in the Sunday services. Those who

could not take their turn at preaching could at least form the nucleus