![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

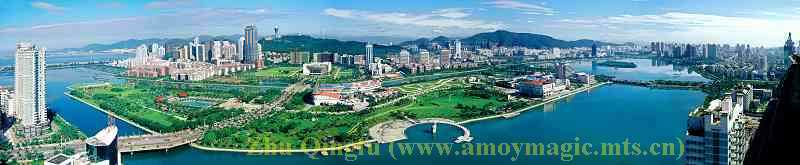

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

Festivals

& Culture

Your hospitable Chinese hosts are bound to invite you to celebrate these

festivities with them. Go for it! But also note that some customs and

taboos differ from ours.

Some local taboos:

1.

Never point at people with the middle finger.

2. Don't sweep in front of guests; they'll think you're shooing them out.

3. Breaking a bowl or utensil at wedding feasts is augurs great misfortune.

4. Never serve a guest six dishes of cooked food. During the Qing Dynasty,

only death row prisoners were fed six dishes right before execution.

5. Don't lay chopsticks across a bowl, lest fishermen's boats run aground.

6. Never turn a fish over to get the meat on the bottom side of the skeleton,

or a fishing boat will sink. (Dr. Jan says, "Lift the skeleton out.").

7. Don't jam chopsticks upright in rice: they resemble sacrificial incense

sticks.

8. Never pat a Chinese adult on the head.

9. Always give and receive gifts with two hands! And when receiving business

cards, don't just stuff them in your pocket. Read them for at least 15

or 20 seconds, compliment the design of the card, then set in on a table

(or place it carefully in your wallet).

10. A person who hasn't 'settled down' (married) can receive HongBao's

(cash-stuffed red envelopes) but can't give them.

11. Mentioning monkeys near babies may cause the babies to get sick.

And speaking of monkeys...

Monkey Business

According to a Xiamen University professor,

Chinese legend has it that we Laowai are the fruit of an unseemly union

between an ancient Chinese maid and a monkey! When I protested, he pointed

to my arm, smiled, and said, "You foreigners are hairier than us

Chinese!"

Tibetans, by the way, are proud of such

monkey business. They boast that all Tibetans are descended from a union

between the monkey God Chenrezi and the mountain goddess who seduced him.

Darwin would be gratified.

Chinese New Year (Chun Jie),

aka Spring Festival, is to Chinese what Christmas is to Westerners. It

falls on the first day of the first month of the Luny Calendar, and so

changes each year, but usually is in January or February.

As the New Year approaches, don't even think of using public transportation.

We were once stuck in Beijing for two weeks because every bus, plane,

truck and boat was packed with gift-laden passengers headed home for the

holidays.

In the countryside, shiny new bicycles groan under the weight of parents

and children returning to their ancestral home with bundles of gifts,

and baskets of live ducks, geese, chickens and piglets. Even in the remotest

hinterlands, mountain paths teem with families making the long but joyful

trek home, possessions slung over parents' shoulders, children skipping

and laughing in anticipation of grandma's cooking and grandpa's tall tales

of the Japanese invasion, and of the revolution.

A

New Year's celebration has always been a very intimate affair, family

only. But either times are changing or we now have a very big family.

When the MBA Center's Dean learned, to his horror, that we had not prepared

our own Chinese New Year feast, he invited us to share his family's 20

course banquet. And every year since, some Chinese family has shared their

intimate meal with this family of homeless Americans.

All around Xiamen you will see traditional sayings in gold letters on

red paper (some with Mickey and Minnie Mouse on them) pasted up on both

sides of doors. They are to insure good luck in the New Year, and a typical

couplet might read:

"May there be lots of things to sell, and lots of money."

"May the marketplace be crowded, with noisy business people."

When

only one character is posted, it is usually for Spring (Chun), Long Life

(Changshou), or Fortune (Fu). They are often placed upside down so demons

can't read them and give them the opposite!

You'll also see round mirrors above some doors, because demons are so

ugly that when they see themselves they are frightened away. And it might

work-at least on Foreign Devils. I've scared myself a few times before

my morning shave.

Red paper is never used if an elderly person has died in the household

within the last three years. Instead, they use green paper if the deceased

was a man, and yellow if they were a woman, and the sayings are calculated

to placate the recently extinquished personage:

"Remember to be reverent for three years."

"Cherish the memory of your parents like a cloud rising to the sky."

"Wholeheartedly remember the past."

"Where'd you hide the safe's key, dear departed Dad?"

The

night before New Year's Eve, families prepare sweets like cooked dates,

Chinese melons, cakes and candied peanuts. In the countryside and those

cities where it is not banned, people set off firecrackers to ward off

demons and the dreaded man-devouring Nian that stalks the land every New

Year's Day.

Lantern Festival

(Yuan Xiao Jie) falls on the 15th day of the Luny Calendar. Be sure to

take in the shows at Zhongshan Park, and buy your kids (or yourself!)

one of the little battery-operated brightly colored plastic lanterns,

and parade down Zhongshan Rd. with everyone else.

According to tradition, young girls prowl about on this night, hanging

around the lanterns, or pulling up people's onions and vegetables, all

in the hopes of getting married. (I've never understood what pulling up

veggies has to do with matrimony, unless she wants to land a husband with

a higher celery?).

Another

practice is for the eligible lass to cast divining blocks, and then to

walk in the direction they tell her until she meets someone. She memorizes

the first word that person speaks, and then a fortune tellers divines

whether the word is lucky or not, and thus whether she will marry or not

that year.

National Day

(Guo Qing Jie). It is ironic that our planet's oldest nation is also one

of the youngest. We celebrate New China's birthday on October 1st, and

usually get 3 or 4 days off for National Day festivities. Most likely

you'll be invited out by colleagues or friends to celebrate with a meal,

and an evening of entertainment that may include fireworks, special performances

of ballet or orchestras, or Minnan Opera. Or you can hibernate at home

and watch the gala specials on CCTV, Shanghai TV, or our own XMTV.

SEND a Free

Dragon Boat E-card !Click the Dragon Boat --->

(Compliments of 123Greetings.com!)

The Dragon Boat Festival! on the 5th day of the 5th lunar month, is called the Double 5th Day Festival in Taiwan, and the 5th Day Festival in Xiamen. Some people still insert Chinese mugwort in the doorway, poor wine on the floor, and pin charms on the children to keep evil spirits away. It's also a great day to air out clothes, clean the house, eat zongzis (pyramid-shaped dumplings of glutinous rice and meat in bamboo leaves), and to watch the annual International Dragon-Boat Race held in Jimei's Dragon-boat Pool. (Some dragon boats in the countryside are so long they require 80 rowers!)

The

Dragon Boat Festival is one of 3 traditional days for settling

accounts with both the living and the dead. Various deities are responsible

for success in health, wealth and warfare, and with lakes and rivers numerous

in the south of China, many Southern deities live underwater. This explains

why some people throw rice and zongzis into the water-to feed the hungry

deities, demons, ghosts, and dragons (the chief water creature being the

dragon). Yet another tradition says the zongzis are thrown to an ancient

poet who drowned himself.

Zongzis supposedly originated with Qu Yuan,??,a Minister in the State

of Chu back during the 4th century B.C. He gave detailed instructions

on how to wrap rice in silk, with threads of five colors. They eventually

came to be wrapped in leaves, in triangular shape, and bound with leaf

fibers or string.

Susan Marie loves Zongzis, and Double Fifth is the time to find them-both

the sweet ones and the meaty ones. Give them a try.

Qingming Festival or Grave-Sweeping Day,

falls on the 105th day after the Winter solstice, or April 5th (which,

lest you've forgotten, is also my birthday). On this festive occasion,

folks eat 'spring cakes,' go for strolls in the countryside, and show

respect to ancestors by sweeping their graves. While some people still

burn 'hell money' to ease the dearly departeds' debts down below, nowadays

more people are just leaving flowers, at both ancestors' graves and the

cemetery of revolutionary martyrs.

The willow has long been used to celebrate Easter because it is one of the first flowers to bloom in spring. Likewise, Chinese use it for Qingming Jie. In fact, tradition has it that women must wear a sprig or risk being reborn as dogs! This tradition began back during the Tang Dynasty when Emperor Gao Cong (650 to 683 A.D.) plucked sprigs of willow and ordered his retinue to wear them in their caps to protect them from scorpion stings.

Oddly enough, another name for Qingming Jie is Zhishujie,or "Tree Planting Festival," and it falls at the same time as the West's Arbor Day (which is also set aside for planting trees).

On grave sweeping day, a meal and 3 glasses of wine are offered to ancestors, candles are lighted, and 3 sticks of incense smolder while the family prostrates itself before the dead. And as a precaution against evil spirits stealing the sacrifices, they often make a separate sacrifice of Hell Money (called ??? Wai Sui Zhi, or Outside Following Paper), which the demons scramble after.

If someone can't make it to the ancestral tomb, they worship by correspondence. They put the Hell Money in large square bags, address it to the deceased recipient, prepare a smaller package for the evil demons, place them on the bed, light candles, kneel and worship. The parcels are then taken outside, wine is poured on them, and they are set afire. Hence the origin of "dead letter mail?"

Cold

Food Festival

on April 4th is yet another cool festival. Fire and smoke are forbidden

because some official was burned to death on that day a few thousand years

ago. In remembrance of this man, Chinese used to forego fire for an entire

month, but they cut it back to 3 days, and now it's only one day, if even

that, and people eat only cold spring rolls, cold noodles, and cold take-out

cheeseburgers and KFC.

So why not just use a microwave?

Mid-Autumn Festival (Zhongqiujie),

also known as Moon Festival, falls on the 15th day of the 8th Luny month.

Contrary to popular opinion, Neil Armstrong was not the first person on

the moon. It was Chang-O, a beautiful lady who fled to the moon back during

the Xia Dynasty (2205-1766 BC). During Moon Festival, worshippers of this

Moon Goddess offer her moon-cakes, tea and fruit, and Hell money.

Just before the Moon Festival, people present mooncakes to family, friends, co-workers and bosses. In Taiwan's private schools, teachers traditionally give mooncakes to students, and students reciprocate with a nice cash-stuffed Hongbao (Red Envelope).

I

wouldn't mind starting that tradition in Xiamen

University.

One tradition has it that on Moon Festival Eve, the later a girl goes

to sleep, the longer her mother will live-so many girls stay up the entire

night.

And once upon a time, on mid autumn festival, unmarried but wealthy girls past their prime would throw an embroidered ball out her window to a crowd of unmarried men below. She could throw the ball to any man she chose, and the one who caught it had to marry her, and they lived happily ever after, or at least had a ball.

In

the evening, families are reunited to eat mooncakes, drink wine, and guess

riddles, and in Southern Fujian and Taiwan, we play Koxinga's "mooncake

gambling game."

Moon-Cake Gambling,

like Minnan Opera, is found only in Southern Fujian and parts of Taiwan.

The game was invented by pirate-cum-patriot Koxinga to keep his homesick

troops occupied.

Every mid-autumn festival, quiet evenings are punctuated by the ringing of dice in large porcelain bowls as families and work unit members gather around tables to compete for mooncakes. They take turns tossing 6 mahjong dice into the bowl, taking care that no dice bounces out (for then they lose a turn).

Prizes range from tiny cookies to medium and large mooncakes, with one grand prize - the Zhuangyuan cake. The different sizes represent different official positions won in taking the imperial examinations of yesteryear. The Grand Prize, called Zhuangyuan, represents #1 scholar, Duitang is #2 scholar, Sanhong is #3 scholar, deng deng.

Few people actually enjoy the green bean and egg and fruit stuffed pastries, but who's going to mess with tradition? Mooncakes probably fill much the same niche as fruitcake back home. Fortunately, many families (and work units) are now replacing mooncakes with fruits, food, or practical things like towels, toothpaste, and laundry detergent. Our family usually wins enough toothpaste from Foreign Affair's annual game to last the year. If we ever miss out on Moon Festival, our Dentist will be the first to know about it.

For more precise directions on Mooncake Gambling, just stick around. Your hospitable hosts will either teach you the ropes or hang you with them. But worry not. 'Tis a piece of cake! So much so that our boys have made a board game out of it, battling year round over hand-drawn cardboard cakes.

Possible

Mooncake Game Combinations:

One red is Yixiu, and lands the smallest cookie.

Two fours, Ligu, gets you a larger cookie.

Higher combinations land larger mooncakes, until eventually you get the

grandprize, or Zhuangyuan - which is four fours or above.

But beware! If you throw Zhuangyuan, don't eat the cake yet. If someone

throws a higher one later, they can take it away from you.

Which just goes to show you can't always have your cake and eat it too.

Winter

Festival

(Dongzhi) falls on the shortest day of the year, the Winter solstice,

and according to custom is the best day for buying, selling, and signing

contracts. On this day, eating a plate of Winter Festival dumplings will

supposedly add a year to your life.

Sending off the Gods Day

is the 24th day of the 12th Luny month. On this day, the gods down here

on earth report to the heavenly emperor on who's been naughty and who's

been nice. To get on their good side, people offer them sacrifices, and

burn spirit money, and give out New Year cakes to friends and family.

This is also the only day they dare to clean house.

According to ancient custom, every single object in a house has a god living in it, so people who still follow old customs (especially in Taiwan) are very careful about how they clean house, lest they jostle and anger the deities resident in the couch or teapot or porta-potty. But on Sending off the Gods Day, the gods have all left to make their reports to the Emperor upstairs.

This is also a good day to marry. Fortune tellers aren't needed to determine if it's a propitious day because the trouble-making deities have all skipped town.

On Weddings & Funerals....Weddings have

been a festive occasion in China ever since they were instituted about

3,019 years ago by Fuxi, whose sister complained to him about the promiscuous

way that people were living together. Fuxi acted on her advice, drew up

marriage regulations, instituted match-making, and the redoubtable Hans

have been henpecked ever since. Early on it was ruled that people with

the same surname could not marry, but given that 1.3 billion Chinese share

only 400 surnames, it's fortunate that this rule was abolished, lest some

bride be force to marry the wang husband.

Traditionally,

Chinese had 8 considerations in selecting a mate: 1) different surname,

2) not related, 3) rich), 4) social position, 5) behavior, 6) health,

7) appearance, 8) lucky or unlucky.

Speaking for myself, I possess # 8, good luck: I'm lucky my wife didn't

belabor the other seven.

Wedding dates are carefully chosen according to the Chinese horoscope, and presided over by seniors in both families. Traditionally, the day before the marriage, the bride's family sends the dowry to the groom's family and decorates the bridal chamber. Early on the wedding day, the bridegroom fetches the bride in a wedding car, and holds a banquet for guests that evening. After the feast, guests can go to the bridal chamber to joke with and tease the bride and groom.

On

the third day, the bride and groom return to the bride's family, where

a feast is held to celebrate their survival of the first 3 days.

But nowadays, many lovebirds forego the feasting and teasing and head

straight for the honeymoon.

Wedding gifts should always be given well before the wedding day, never on or after it. But if your friend hands you a sack of sweets and says they've just been married, no gift is expected.

Wedding gifts used to be practical, like Double Happiness Brand thermoses, blankets, electric rice cookers, electric fans, deng deng. But to avoid getting five rice cookers and four fans and thirteen thermoses, many now prefer the increasingly ubiquitous cash-stuffed Hongbao.

Though

"Hell Money" may be best for dearly departed newlyweds…

Till Death Do Us Marry Even with divorce

rates sailing past 50%, Americans still staunchly vow, "Till death

do us part." But not even death unties the knot for Chinese. In fact,

some don't even marry until after they're dead.

In Chinese communities worldwide (though rarer in the mainland), spiritualists sometimes inform bereaved families that their dead child cannot rest until married to some other dearly departed soul. Both families then spend a small fortune to wed the dead, who attend by proxy (often in the form of engraved wooden 'spirit boards,' to which sacrifices are offered).

I

suspect some girls end up with some real deadbeat husbands.

And speaking of dead folks… China not only has the largest population

of living, but the most dying as well, so you may be invited to a funeral.

Funerals, even more than weddings, have brought home to me just how alike,

in the end at least, are we Laowai and Laonei.

Filming a Buddhist Funeral

The village square facing the ancient Buddhist temple was crowded with

old and young alike, and a few dogs and chickens as well. I walked up

and down with my video camera, filming the funeral of my student's father.

Per his request, I filmed everything. I panned the gifts of blankets draped

over bamboo poles, and the rickety table covered with food offerings to

the deceased, whose photo was propped up on the table so he could oversee

the proceedings.

As

I filmed, everyone who saw me shouted "Laowai!" This shouting

and pointing gets to some Laowai, but look at the other side of the Yuan.

Laowai zip about snapping shots of old men in PJs brushing their teeth

on the roadside, or of fishermen mending nets, or babies in split pants,

as if they all were Smithsonian cultural exhibits. I'm not sure which

is worse, "Laowai!" or "Flash!"

Yankee

Doodle Dirge

Mourners and curious onlookers watched the deceased's family bustle about

preparing food for the growing crowd. Shaven headed, saffron robed Buddhist

priests bustled about preparing for the service. And three bands played

simultaneously. A white uniformed brass ensemble played Western music,

ranging from Sousa's marches to Camptown Races. An ancient trio played

classic Chinese instruments like the suona (a brass horn shrill enough

to wake the dead or exorcise them), and the two-stringed erhu (Chinese

violin), which is often high pitched and shrill but in the hands of a

master is as sweet as any Western violin. A third ensemble played Spanish

flamenco on guitars. The icing on the corpse's cake was a Chinese ghetto

blaster blaring a funeral dirge that cast a mournful pall that no one

could bear (except, perhaps, the pallbearers).

Just

about the time I felt like joining the mourners myself, the brass band

broke into a rousing rendition of "Yankee Doodle Dandy."

Chinese funeral music appears to emphasize volume, not quality. Perhaps

it's like the 100 million dollar hell notes, and false bottomed baskets-the

dead don't know any better. Besides, funerals (like weddings) can bankrupt

you, so why waste money on good music for the deceased when their ear

for music is dead anyway?

Farewell Forever After an hour of solemnities, the relatives led a procession out of the village common and down the dusty path into the countryside, marching to the three bands' merrily mournful music. Behind the bands came the pallbearers, followed by the sons, more family, professional mourners, a solo guitarist playing Spanish music, hundreds of friends and curious onlookers, children, dogs, and one lone water buffalo, who must have known what he was about because everyone ignored him.

And I ran back and forth filming the entire procession.

The

sons' devastating wails reached new heights when we passed a beautiful

3-story partially completed home on the outskirts of town. It was to have

been the father's retirement home.

After marching far out into the countryside, the mourners took a left

fork in the road back to town and the male family members continued on

with the coffin towards a small copse in the middle of a dusty field.

We passed into the shadows of gnarled, ancient oaks, and approached a

dark, musty cave piled high with moldy urns and bones, a few leg bones

here, a thigh bone there, a pile of skulls on a shelf.

The place had obviously seen its share of skullduggery.

The sons lifted the blanket and I nearly dropped my camera in shock. I had thought the father lay in state in a coffin, but under the red blanket was naught but a small porcelain urn of ashes.

(Given how much he smoked, I think the extinguished gentlemen would have preferred a lacquer ashtray to an urn).

The sons placed the 8 x 10 and the urn on a shelf dug into the damp cave wall, I shot one last scene, and we returned to the village courtyard, which was already cleared out and deserted, as if the funeral had never taken place.

Life goes on.

Weddings and funerals. Life and death. We Laowai and Laonei really do have a lot in common. As someone said, "Life is tough, and then you die." But Chinese are certainly no strangers to suffering, and I increasingly appreciate their love of life, and even their ability to laugh at death, as in these ancient Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) tales:

Live to Tell About It-a Ming Dynasty Tale

On his sickbed, retired prime minister Ye Heng asked a visitor, "I

am dying. Is death a desirable state?"

"Yes, of course it is!"

"But how do you know that?" Ye Heng asked him.

"If it were so bad," the visitor said, "they would have

all come back by now, but since none have returned, they must be happy

over there!"

Red Sorghum-a Ming Dynasty Tale A man complained

to his friend, "Your mother has just died and instead of mourning

you are eating red steamed sorghum!"

The friend replied, "Then I suppose those who eat white rice every day are in mourning?"

Cultural Supplement

These Are the Magi-- Gift-giving in China

He who gives when he is asked has waited too long.

Chinese Proverb

The

Art of Chinese Gift-giving

It is written that the wise men who brought gifts to the Christ child

came from the East. I suspect they meant China, because 1) you can't get

any further East than China, and 2) Chinese have raised giving to an art

form.

Our

first Christmas in China, our elderly dean gave our two sons a toy electric

car that set him back at least a week's wages. Two months later, on Chinese

New Year, a teacher gave each of our sons a Hongbao (Red Envelope) stuffed

with 100 rmb-a small fortune by that teacher's standards. Any doubts on

the importance of gifts in China vanished when I read Lesson 38 in, "Modern

Chinese Beginner's Course." The correct response to an impromptu

invitation to a Chinese friend's home was, "But we haven't brought

any gift."

Gift

giving rituals vary around China. Tibetans give a white silk scarf, while

Hainan Islanders place a lei of flowers over guests' shoulders. In Xiamen,

the most common gifts are bags of fruit or packages of our local Oolong

tea.

Xiamen folk avoid giving odd numbers of gifts. It must be two bottles of Chenggang medicinal wine, not one or three bottles, or 4 boxes of Tiekuanyin tea, never three or five. The gifts must be proffered respectfully with two hands, and accepted with two hands.

Americans have no qualms in giving an inexpensive gift or card to convey a sentiment because it's the thought that counts. But not in China, where face is everything, and a small or trifling gift may be worse than no gift at all. Conversely and perversely, the larger the gift, the more face for both parties. Over the years, our face has been lifted more times than Elizabeth Taylor's.

Guests have materialized on our threadbare astroturf welcome mat with 50 bananas, or 30 pounds of roasted Longyan peanuts, or 15 pounds of freshly caught fish, or 4 dozen freshly fried home-made spring rolls. We've protested, futilely, that 50 pounds of bananas will rot before we can finish them off. In the end, we either go on banana binges or make a quick pilgrimage to a Chinese colleague's home with a second-hand gift of bananas, tea, dried mushrooms or fresh fish. They probably pass them off too, but somewhere down the line some soul has to get 50 pounds of bananas down the hatch.

Where's the Beef? We had some knotty experiences until we learned the ropes of Chinese gift giving. Shortly after we moved into Chinese professor's housing, Susan baked chocolate cake, which at that time few Xiamen folk had tried. She gave our neighbor a couple of slices to sample, and the astonished granny thanked her profusely and shut her door slowly, politely. Next morning, bright and early, she rapped on our door, and thrust a plate full of beef in Sue's face. She said, "For you," and beat a hasty retreat, ignoring Susan's protests.

"This is terrible, Bill," Sue said. "She should not have done that."

"This is great, Sue." I retorted. "Two pounds of beef costs a lot more than two slices of cake. Think how much we'll save on meat if we give cake to all our neighbors."

Now

I know why Marie Antoinette gave everyone cake.

It is Cheaper to Give Than to Receive Nowadays,

we are more careful (though not paranoid!) with gift-giving, because it

can be costly for all concerned. Those whom we give gifts feel compelled

to reciprocate, whether they can afford it or not. As for receiving gifts…

they sometimes have more strings than ribbons. But all things considered,

I still think Chinese are the Magi-particularly where family and homeland

are concerned.

Giving to the Motherland When overseas Chinese labored in abject poverty in the mines and fields of Africa and Colonial Asia, or to build American railroads, they invariably sent a large portion of their meager earnings home to family. It was these pittances, multiplied a million fold, that kept China afloat when we were bleeding her dry through the opium trade.

Some laborers became industrial magnates, like Tan Kak Kee, and donated millions to China. Even today, regardless of political persuasions, overseas Chinese continue to remit millions annually not only to their mainland relatives but to local governments to build schools, colleges, orphanages, and roads.

Chinese, rich and poor alike, are a generous people. A lowly mason who lives in a shack nearby gave me 5 pounds of freshly netted fish because he heard my in-laws were visiting from America. A disabled, retired campus laborer shows up occasionally with fresh greens from his garden, or new flowers for our yard. When word got around that I wanted a stone mill to grind wheat, several peasants headed to the rural stone quarries, and we were blessed with not one mill but three (never again will I take wheat for granite).

The mason, the disabled laborer, the peasants, sought nothing in return. They gave because we were friends-like the poor bicycle repairman who repeatedly insists, "It's a small thing. Pay me when you have a real problem to fix." The man's entire world is but a tiny, dusty shop only 8 feet wide and 4 feet deep. Greased bike chains and sprockets, rims and tires and tubes, bike seats and pedals hang from nails on the walls. His furniture consists of two bamboo stools, one for himself and one for customers, and a bamboo footstool that doubles as a table for his cheap tea set, which he sets up every time I stop by.

He has spent more serving me tea than he will ever make from fixing my battered bicycle.

Chinese have always given sacrificially to family and their immediate community, but charity beyond that was rare, for it was seen as depriving family and local community of scarce resources. But times are better now, and Beijing is seeking to widen the scope of giving.

Half a dozen programs encourage wealthier urbanites to help their less fortunate and far more numerous comrades in the countryside. Every year, "Project Hope" (????) allows millions of urban Chinese to help fund poor rural children's education. And "Helping Hand" pairs up city kids and country kids, who write to each other and exchange gifts.

Get involved!

Many foreign firms and individuals have participated in campaigns like

Project Hope. For details on how to get involved, contact your Chinese

colleagues or the municipal government. You can even arrange with local

governments to help sponsor schools or poorer students. Opportunities

are limited only by your imagination and your purse.

Gold Rats and Oxen - A Ming Dynasty Tale

(1368-1644)

On his birthday, an official's subordinates chipped in to give him a life-sized

solid gold rat, since he was born in the year of the rat (each year of

a twelve year cycle has a different animal). The official thanked them,

then asked, "Did you know that my wife's birthday is coming up? She

was born in the year of the ox."

![]() Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites ![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album ![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides ![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn ![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn. ![]() Roundhouses

Roundhouses

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Jiangxi

Jiangxi

![]() Guilin

Guilin

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books

![]() Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY

LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top