![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

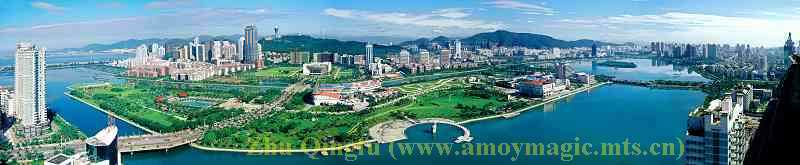

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

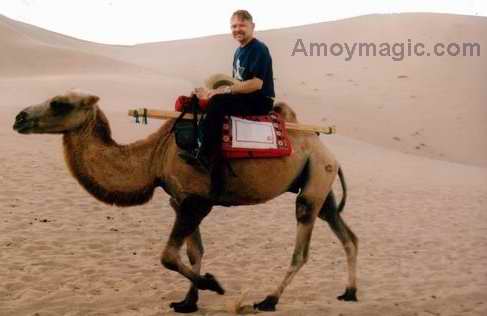

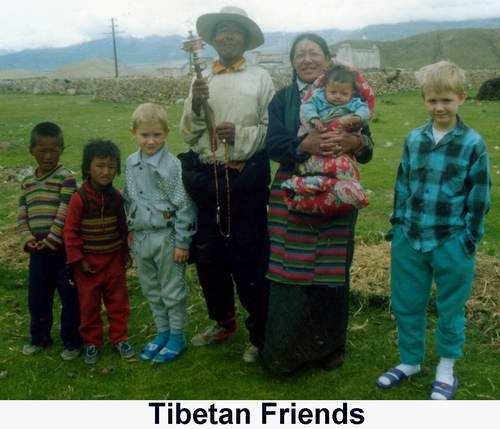

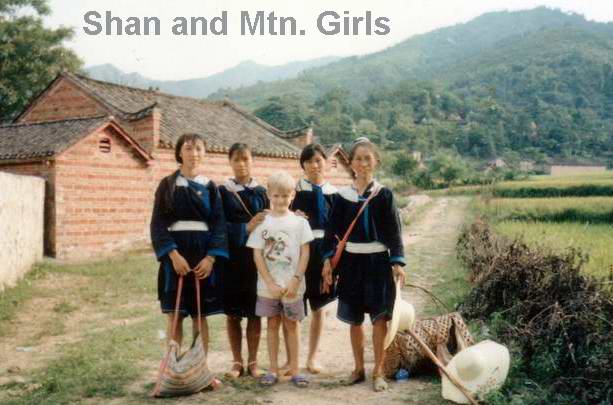

Tibet or Bust--Around China in 80 Days!

Author’s Note: These are notes (unedited,

so bear with me) from our October 1994 three-month 40,000 km. drive around

China. We drove up the coast and over to Mongolia, descended through the

Gobi Desert, crossed the 17,300 foot pass into Tibet, and returned to

Xiamen via S.W. China. And after 40,000 km., the only place we got stuck

was in a pothole on Xiamen University, just 300 meters from our apartment!

I hope you enjoy the journey!

Dr. Bill Xiamen University MBA Center

Clover Leafs and

Daisies More people kick off during predawn’s

preternatural cold silence than at any other time, so perhaps it was an

inauspicious hour to kick off our trip. As we sped out of Xiamen on the

morning of June 24th, 1994, our motto “Tibet or Bust,” we

almost kicked off more than the trip.

Our 50 mph speed on Xiamen’s new 6 lane highway was a welcome relief

from the 15 mph we usually crept at on highways and low ways alike –

until we reached the new cloverleaf. The ramp rose into the darkness and

– vanished! I screeched to a halt, and inched up to its edge. It

was unfinished, and led to a 30 foot drop off. The only warning was a

chunk of wood with a smeared chalk scrawl, but it had fallen over.

I wondered how many Chinese drivers were already pushing up daisies under

that cloverleaf. It was a good reminder that caution was in order if we

were to survived the remaining 39,995 km of our 40,000 km journey.

We crossed Xiamen Island’s causeway, then drove up the coast, past

Marco Polo’s ancient port of Quanzhou, and Fuzhou, the provincial

capital in the north. We spent a restful night in the tiny town of Luoyan,

where a two room suite in the newly renovated hotel set us back only $9;

they were obviously new at the tourist game. At daybreak, we continued

our drive northward, winding up and down and around mountains and through

Fujian’s deep, forested valleys, past terraced fields dotted with

villages, temples and enough steepled churches to give it the feel of

an Asian New England.

Return to top

None too soon we left Fujian behind us and entered Zhejiang Province,

where we headed inland towards LiShui (beautiful water) town – aptly

named! On the very short outskirts of the very small town, we pulled off

onto a sand bar beside a shimmering river the hue of turquoise in Navajo

jewelry. The four of us waded through the rocks garnering bright green,

red and purple pebbles. The shy, barefooted peasants in their bright scarves

and not so bright blue Mao pants and shirts watched us for awhile, perplexed,

and then they too began sifting through the river bed. When they offered

us the smooth, jade colored rocks they had collected, I thought they were

trying to sell them, but not the case. They had no idea why we wanted

worthless rocks, but they had decided to help us out anyway. Aiyah! Foreigners!

After a grueling 15 hour day of driving, we finally sighted Hangzhou across

a river. So close and yet so far. In spite of directions from half a dozen

people, it took two hours to cover the last 5 kilometers.

China has a dearth of traffic signs, even on major highways, so Shannon

and Matthew worked the compass, I worked the map, and Sue second-guessed.

This worked in the countryside, where there weren’t usually more

than two roads to choose from anyway, but cities, with their one-way streets

and dead ends, were another ball game.

The problem is that the locals responsible for erecting signs don’t

need them and so don’t erect them. The few token signs that they do put up

point to one-ox towns that outsiders have never heard of and aren’t

looking for. The fact that natives already know how to find such one-ox

towns confirms the futility of signs. When we did find signs, quite often

they pointed the wrong directions, and in the remote mountains of Sichuan,

near Tibet, peasants put workaday signs like, “Dangerous Curve Ahead,”

to better use by painting over them, “Firewood!” or, “Eat

Here!” After all, locals already knew about the curve and it wasn’t

going anywhere.

and so don’t erect them. The few token signs that they do put up

point to one-ox towns that outsiders have never heard of and aren’t

looking for. The fact that natives already know how to find such one-ox

towns confirms the futility of signs. When we did find signs, quite often

they pointed the wrong directions, and in the remote mountains of Sichuan,

near Tibet, peasants put workaday signs like, “Dangerous Curve Ahead,”

to better use by painting over them, “Firewood!” or, “Eat

Here!” After all, locals already knew about the curve and it wasn’t

going anywhere.

Return to top

Asking directions is never a simple recourse, because no one ever pleads

ignorance. You ask and face dictates that they answer, whether they know

or not. We always queried 2 or 3 people and shot for a consensus, and

even then we were thrown for a few loops (one that took us back towards

Tibet when we had spent a week trying to get out of Tibet, and delayed

us 3 days).

A year earlier, during a trek around Fujian Province, one of my Chinese

friends had asked a Nanping native the whereabouts of our hotel. When

he pointed to the left, I warned my friend, “Ask someone else. He’s

bluffing.”

“How do you know?” my skeptical passenger demanded.

“Because he hesitated and looked both directions before he answered.

He’d never make playing poker.”

Sure enough, the hotel was to the right, not the left.

Return to top

Hooked on Hangzhou “Heaven

above, Hangzhou and Suzhou below!” Or so goes the ancient saying.

Hangzhou is a wonderland of gardens, lakes and forests. And in 1994 it

may have been the cleanest city in China. I asked a man on the street,

“With so many tourists, how do you keep the place so clean?”

He laughed. “If we treated Hangzhou like a garbage dump, tourists

would do likewise. But we respect Hangzhou and keep it clean, and so do

visitors.”

The Silk Museum was our favorite attraction, with its

display of ancient and modern silks, and detailed explanations of various

silk making techniques. I had no idea there were so many kinds of silkworms;

they dine not just on white mulberry leaves but also on oak leaves, osage

orange leaves, and lettuce. Hold the tomatoes.

The museum’s pretty young guides collected half a dozen silk worms,

placed them in a shoebox lined with fresh mulberry leaves, and presented

it to the boys. The worms, of course, outlasted the mulberry leaves, forcing

us into a life of crime as, over the following days, we snitched leaves

from roadside trees until the worms had spun their silky cocoons.

Weeks later, as we cruised along the arid heights of the Tibetan-Qinghai

plateau, the moths emerged and flew around inside the van, to the boys’

delight, and I wondered what Tibetans thought when silk moths showed up

on their welcome mats.

Chinese have treasured silk for millennia. Over 6,000 years ago, in Banpo,

near Xi’an, artisans designed pottery bowls with gauze prints using

silk. In Wuxing county, archaeologists have dug up herringbone silk belts

and silk thread buried over 4,700 years ago. Silkworm breeding was already

a major industry 3,000 years ago, during the Shang Dynasty. The emperor

assigned a special agricultural official to supervise silkworm production,

and sacrificed three cows or six sheep to the Goddess of Silk Worms to

insure an ample harvest of cocoons.

Return to top

Modern technology has made vast improvements in silk production techniques.

Silkworm raisers used to paste pictures of cats on the egg-tray to scare

away mice. Today, they supposedly get better results by playing recorded

‘meows.’

Science has also helped silkworm growers fight age-old diseases. To prevent

the spread of the muscardine plague, silkworm growers used to immediately

swallow whole any infected cocoons discovered during their daily inspections.

Today they simply apply an anti-muscardine powder (though some might still

eat the cocoons since muscardine-infected silkworms are supposed to be

good for treating headache, sore throat, convulsions and tuberculosis).

After three days in Hangzhou, we wound our way up a road that slithered

like a black snake along the tight curves that garrote Mo Gan Mountain.

The trees and bushes waved in the balmy breezes that, before Liberation,

made Mo Gan Mountain a favorite haunt for wealthy foreign colonialists

seeking respite from the heated plains below.

Giant bamboo blanketed the mountains so thickly that they appeared to

be covered with giant green feathers, waving in the wind. But when the

road led us beneath the towering bamboo, they became verdant cathedrals,

or an endless living tunnel opening into the preternatural light that

in the end none escape.

As we inched around the hairpin curve, the bamboo cover sometimes gave

way to a magnificent view of Swiss-looking villages, their wooden shingled

homes with their carved wooden balconies nestled in the alpine valleys

far below. I could have happily spent a summer on MoGan Mountain, but

we were already behind schedule, and after too brief a stay we pushed

on to the Great Ditch.

Return to top

Grand Canal We descended

from the lofty retreat of MoGan Mountain and reentered the plain and the

furnace, where we followed the Grand Canal to Suzhou. This busy waterway,

almost a 1,000 kilometers in length, is still congested with hundreds

of “water trains”-- low-slung concrete barges, strung together

ten or more, plying the waterways with cargoes of construction materials,

coal, grain, produce.

Ancient cities, like Rome, London, and Alexandria in the West, or Xi’an,

Hangzhou, Nanjing and Beijing in China, flourished because of their proximity

to water. But ancient Chinese went a step further. Great natural rivers

linked ten Chinese provinces, but these waterways flowed mainly from West

to East. Traders going North or South were out of luck. So Chinese made

their own rivers.

In the 5th century B.C., China began construction of a great North-South

canal system that not only facilitated transportation but also allowed

irrigation of fields and expansion of food production for China’s

already burgeoning population. The construction continued 1,800 years,

and eventually covered 1800 kilometers.

Canal construction was on and off, but it reached its height during the

Sui Dynasty (581-618). As much as possible, canal architects made use

of existing lakes and rivers, connecting them with 7 canals.

In 605, Emperor Yangdi ordered a million laborers to dig the Tongji Canal

– not so much to improve commerce as to tighten his political control

and to make it easier to transport the taxes, cloth, and grain that he

exacted from his subjects. In that same year, another 100,000 laborers

were ordered to expand the Hangou Canal. Both these canals were 60 to

70 meters in width, and both canals were lined on either side with poplar

and willows.

Chinese still follow their ancient practice of lining roads and canals

with greenery. Before a new road or highway or canal or ditch is finished,

crews of laborers are busy planting hundreds of trees up either side,

and down the grassy median. These saplings are often to replace the hundreds

of ancient, beautiful trees destroyed during construction, but in the

long run, it is invariably aesthetically pleasing. And that’s how

Chinese look at things – the long run. The very long run.

Return to top

Though Chinese woodsmen may appear a bit cavalier with the run of the

mill pine or scrub oak, they almost never dig up a giant banyan or oak

tree, even for a major highway. They detour around, and not out of some

superstitious reverence for trees but out of sheer respect for an ancient

life. It’s refreshing to see a six lane highway making way for a

tree. Though the curves could be a little gentler. It’s disconcerting

to be driving along at 60 mph and come up on a 70 degree curve around

a 500 year old banyan tree. Though it may be Comrade Kato’s way

of securing a steady supply of quality fertilizer for brother banyan.

Three years after Emperor Yangdi began the Tongji canal, he called up

yet another million ditch diggers to work on the Yongji Canal, and 3 years

later, in 611, the Emperor surveyed his sparkling new canal in a four-deck

dragon boat over 13 meters high and 59 meters long, with a retinue of

tens of thousands of men aboard several thousand ships and smaller boats.

Within two centuries the Chinese government had developed strict administrative

and shipping regulations, and were controlling water flow with highly

advanced reservoirs and double locks much like those in use today, 1,000

years later – and fully five hundred years before the first lock

was built in the West in Italy, in 1481.

Alas, the Grand Canal, like the corrupt Qing Dynasty, began to deteriorate

at the end of the 18th century, largely because of poor water management

and corrupt officials who neglected their duties and took bribes from

ever larger and overloaded smuggling vessels. In 1902, Qing rulers dismissed

the water management officials and abandoned canal transport entirely,

and rail transportation took over. It wasn’t until after Liberation

in the 1950s that the canal was restored to make water transportation

once again feasible, though by the 1950s China had little left to transport.

Return to top

Highway Jailbait Highway

hypnosis is a rare affliction in China,  what

with the constant dodging of people and pigs and cows and chickens and

cyclists and kamikaze cabbies and truckers. But the monotonous scenery

(for the Grand Canal is magnificent, but it is very long, and water trains

pretty much lose their novelty after you’ve seen 6 dozen) and the

smooth highway nearly lulled me to sleep until a policeman flagged me

back into reality and informed me sternly that I had passed in a no-passing

zone. But he let me off with just a warning and turned his attention to

the other two dozen cars and trucks he had pulled over.

what

with the constant dodging of people and pigs and cows and chickens and

cyclists and kamikaze cabbies and truckers. But the monotonous scenery

(for the Grand Canal is magnificent, but it is very long, and water trains

pretty much lose their novelty after you’ve seen 6 dozen) and the

smooth highway nearly lulled me to sleep until a policeman flagged me

back into reality and informed me sternly that I had passed in a no-passing

zone. But he let me off with just a warning and turned his attention to

the other two dozen cars and trucks he had pulled over.

It is no wonder highway police catch more illegal passes than an NFL player.

Slow vehicles, like trucks and farm tractors, though supposed to hug the

right, invariably hog the center, crawling at 3 to 5 mph and forcing motorists

to either make a career of tailing them or to pass illegally. Police lurk

along the slimy slug trails, waiting. I’ve never once seen these

mechanized snails pulled over, but pass them and you’re jail bait.

Venice of Asia I regret relegating Suzhou, the famous,

canal-lined “Venice of Asia,” to one paragraph, but the place

was so oppressively hot that the most memorable thing about our 3 day

stay was the “3 Star” Suzhou Hotel’s A/C; or more precisely,

the lack of A/C.

Return to top

Lukecool A/Cs We had forgotten that Chinese hotels install

central A/C in lieu of window A/Cs not for their guests’ benefit

but for their own--to keep power bills down. The rooms were stifling by

day, and by night the management shut off the air altogether, intoning

the litany we hear on trains: "A/C is unhealthy at night." Although

we enjoyed exploring Suzhou’s magnificent rock gardens, winding

streets, and narrow canals, 3 days was all we could take, and we fled

north to Nanjing--out of the frying pan, and into the fire.

Southern Capital Nanjing was, for a time, the capital

of China (Bei jing means “Northern capital,” and Nan jing

means “Southern capital”), and we wished we’d allotted

more than one day for touring it, but Tibet was still weeks away.

Nanjing is a stately, immaculate city, with tree-canopied avenues, ancient

buildings, modern plazas, and classical parks and gardens. It is also

home to the world famous Nanjing Theological Seminary, which we visited

briefly, though it was Sunday and no one was about.

The staid city really came to life at night. Trees and shrubs and buildings

were festooned with festive strings of Christmas lights, which Chinese

everywhere enjoy year round. Streets and night markets bustled with shoppers

haggling over imported jeans and T-shirts, famous Nanjing gem stones,

fried chicken. And fried people.

In the Furnace One of China’s "4 furnaces,”

Nanjing was over 100 degrees. At least 10 people died of heatstroke the

week prior to our arrival. After one night in a university guesthouse,

which boasted an asthmatic central air conditioner that wheezed lukecool

air by day and nothing at all by night, we headed north to China’s

Bavaria, Qingdao – with a detour to Jiangsu Province’s Donghai,

site of China’s largest crystal market.

Return to top

We hoped to make some additions to our mineral collection back home, but

we almost abandoned that idea when we discovered that the road was a pockmarked,

one-lane dirt path through rice paddies, and Donghai was still 79 kilometers

away. We finally girded our loins and took the plunge, but it wasn’t

much of a drop. After only 15 km, the path broadened into a beautiful

two-lane, tree-lined country road.

Sue created a sensation buying fruit from farmers who had never seen foreigners.

They laughed excitedly and talked a mile a minute while Sue paid so little

for a bag of beautiful apricots that she felt guilty. When she tried to

pay a little extra, they refused – and instead threw a few more

apricots in our bag.

Return to top

Crystal Clear At Donghai's famous Crystal Market, we

bought a few natural crystal formations. A few months later, when we showed

them to a Xiada professor, he argued, “There is no way those are

natural!” He pointed to the quartz crystals jutting from a chunk

of quartz in a fountain of frozen light, and said, “Stone workers

carved this and fooled you into buying it.”

“Really?” I showed him a large rock that Shannon had found

in the crystal quarry of Hainan Island. “Is this natural?”

“Yes, but that’s just a rock!”

I flipped the ordinary chunk of quartz over to reveal perfect hexagonal

quartz crystals. My colleague gasped. My ardently atheistic friend carefully

studied the collection of crystals we have under glass, displayed on black

velvet and illuminated by a hidden florescent bulb, and concluded, “These

aren’t natural, they’re supernatural!”

The psalmist said, “The heavens declare the handiwork of God.”

So does everything under the heavens, and under the earth as well. Nothing

surpasses the elegant artistry of natural crystals – the prismatic

blocks of pink rhodonite, and calcite crystals, steel-gray metallic stibnite

crystals, cubes of halite (the not so common table salt), octahedral blue,

green and violet fluorite crystals, and emerald-like crystals of apatite

(which is taken from the Greek word meaning “to deceive” because

its colors and forms easily fool amateurs). And my favorite -- the purplish

quartz called amethyst.

The book of Revelation likens the light and the sea of the New Jerusalem

to crystal, but this life already has crystals of quick frozen Light for

mortal enjoyment and a foretaste of visual feasts to come.

We left Donghai’s crystal market in search of a reasonably priced

hotel, but the local establishments were obviously used to cadres on expense

accounts. While Uncle Song could afford $50 U.S. per night, we could not

– especially when the prices were doubled for foreigners. About

2:00 a.m. we abandoned our search, pulled into a truck stop, and spent

the night in our van.

Return to top

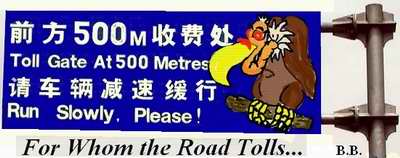

For Whom The Road Tolls

We pulled out of the truckstop at daybreak and made our way up the coast

to the former German colony of Qingdao, perched precariously on the eastern

tip of Shandong Province. We spent 3 days in a colonial-era guesthouse

that was like a slice of Bavaria served up on china, and we combed the

beaches, and sampled authentic Shandong Chinese dumplings in the small

stalls and restaurants nestled between Bavarian homes and cathedrals.

And then we hit the road again, our sights set on Beijing.

Happily, the northbound road was a new expressway, off limits to non-motorized

vehicles and pedestrians (though many farmers jumped the fences or cut

the wires to cross the highway or to sell melons to motorists). It was

almost highway heaven. Almost. I slowed down at a large, “Exit,

Gas!” sign, only to slide to a stop at the 20 foot drop off. Nice

sign, but no ramp yet. Shades of Xiamen cloverleafs!

At only 55 yuan, the Qingdao Freeway’s toll was a bargain. We did

250 miles in six hours, a full 60 miles more than we usually averaged

in ten to twelve hours. But all too soon we exited highway heaven and

reentered reality. Shannon whipped out his little compass, sighted north,

and we headed towards a toll bridge and, hopefully, Beijing.

Every county and one-ox town in East China is vying to build the most

beautiful, modern, glass and bathroom tile tollbooths, many boasting 4

and 6 lanes. But invariably they barricade all but one lane, and force

traffic to jostle through it like cattle through a chute while one attendant

takes the toll and the others sip tea and contemplate the backed up traffic.

The tollbooth is often on the passenger side because, unlike in America,

most vehicles have passengers. But since the driver is usually the one

that pays, the money must pass between the driver, the passenger, and

the toll taker. To further slow things down, the table of tolls, which

explains how much for each class of vehicle, is usually small, and faces

the toll booth, not the incoming cars, so you have no way to prepare correct

change in advance. And if there’s no sign at all, you have to wait

until they’ve sized you up and levied whatever toll they think they

can get out of you.

Return to top

People don’t often line up to get on or off a bus, or to buy stamps,

or to deposit money in a banking account – and drivers don’t

line up at tolls. As you approach the tollbooth you must be carefully

tailgate the car in front, because if you leave the slightest gap, drivers

trying to jump the line from both sides will squeeze in front, using the

‘zipper’ technique. And once he’s nosed in, you’ll

never recover ground because he has a line of nose to bumper line jumpers

behind him.

After you pay the toll, you drive forward 20 feet to show your receipt

to yet another officer, and then you cross to the other side of the bridge,

where yet a third person checks your stub. Three stops, and fifteen minutes,

to cross a 500 meter bridge. But things are improving. In ‘93, I

spent over ten hours trying to navigate a Guangdong traffic jam, but a

year later a beautiful new beltway got me around the entire city in only

10 minutes.

But it took 15 minutes to pay the toll.

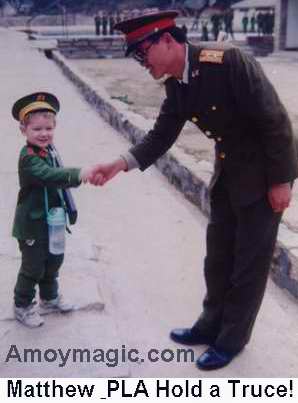

We eventually made it across the toll bridge and cruised down a peaceful,

tree-lined country road, pulling up at dusk in front of a small military

guesthouse. The soldiers had never seen a foreign family drive up in a

Toy Ota but they were hospitable, the room was fairly nice, and they had

window A/Cs, which we inspected carefully before we paid our deposit.

Then we plopped on the bed in front of the A/C and enjoyed cool air every

bit of ten minutes before the malevolent machine coughed, sputtered, wheezed

and ground to a halt. The officer in charge apologized, though, and found

us another room, and we slept the sleep of the dead. Not a good choice

of words.

Return to top

The road through Hebei Province was, for the most part, a wide, well paved

highway, with a grassy median, and tree lined bike paths up both sides

– but there was no on ramp for the Tianjin highway. I plunged the

van off the side of the road and slogged through mud, passing trucks mired

up to their axles. When we reached the bottom we were told by a stranded

trucker that the only way to get onto the freeway was to go back up the

muddy embankment and backtrack ½ an hour to an intersection we

had missed earlier, as it had no markings. It is a lot harder slogging

up a mudslide than down it, especially in a 2-wheel drive van. It took

half an hour to gain the top again. I backtracked, found the elusive intersection,

and headed north to the Tianjin Beltway.

The problem with beltways is finding the buckle. If you get lost you can

go in circles forever. I circled the entire Tianjin beltway twice before

I saw the exit for the Tianjin-Beijing highway. But it was a beaut, rivaling

anything in America.

As we approached Beijing, we saw a gang of youth standing on an overpass.

They had cut the chain-link fence and as we passed beneath them they rained

rocks and trash on us. And nails. Our first flat tire in days. I reported

the delinquents at the tollbooth but the official shrugged apathetically.

It wasn’t his car, after all. But at least Chinese youth only use

rocks, trash, and nails, not guns. So far, anyway. With enough American

television, that might change.

We were so relieved to reach, at last, the beautiful Beijing beltway –

only to discover that it was closed for road construction. All traffic

was forced into a tiny detour.

We inched down a tiny alley past bicycles and pedicabs, between fruit

and vegetable vendors, and eventually reached a dead end. Not a sign in

sight. It took us 2 hours to reach our hotel, which was only two miles

from where we’d left the freeway.

Road construction notwithstanding, our third trip to Beijing was as enjoyable

as the first two. We again visited our favorites -- the Beijing Zoo, the

Forbidden City, Tiananmen, the Great Wall, the Temple of Heaven, Baskin

Robbins 31 Flavors (they only had 9, but whose counting?), Wangfujing

tourist shops and bookstores, and the largest Mcdonalds in the world (which

was later razed, along with everything else on Wangfujing road, when they

built a large mall).

Return to top

Off The Great Wall Chinese

say you are not a real man until you’ve climbed the Great Wall (called

the “Long Wall” in Chinese). Now even Susan is a real man.

Which is just as well since she wears the pants in the family.

‘Great’ is an understatement for this structural wonder, which

for a thousand years protected China and shielded the Silk Road, allowing

a millennia of trade from Xi’an to Istanbul. Contrary to popular

belief, the wall was built to keep out not the Tartars but their horses.

After all, any determined warrior with ropes and ladders could scale an

isolated section under cover of darkness. But getting horses over the

wall was another matter. And while Tartars on horseback were invincible,

on foot they were no match for Chinese warriors, who in short order made

Tartar sauce of them.

The Great Wall’s total length, if you add all the sections built

over the centuries, is supposedly 50,000 kilometers. The walls, trenches,

thousands of beacon towers and forts were all built, wherever possible,

of local materials, and had they used that material to built a wall five

meters high and one meter thick, it would have encircled the earth over

ten times. I can’t imagine what kind of toll they’d have charged

for that one.

The oldest section, about 500 km. long, was built in the 5th Century B.C.,

and stretched from Qingdao on the coast to Jinan. During the Qin Dynasty,

300,000 soldiers and hundreds of thousands of conscripted civilians spent

9 years completing the wall by linking older sections. Qin and Han dynasty

law required that every man spend a minimum of one year of his life building

or guarding the Wall. In 555 A.D., 1.8 million people were conscripted

to build a 450 km section in Shanxi. Millions of soldiers and criminals

also did their part. Han Dynasty records reported that corpses crowded

the wilderness and blood flowed thousands of miles. The Ming dynasty poet

Li Mengyang wrote, “Half of the men conscripted now lie dead before

the Wall.”

Return to top

Few people know that China’s bloody Boxer Rebellion (circa 1900)

was touched off by an Off the Wall joke in Colorado. In 1899, 4 news reporters

from the Denver Post, Time, Republican and Rocky Mountain News, desperate

for a Sunday story, decided to invent one. They picked China, because

it was a long way off and no one would check up on it. On Sunday morning,

all 4 rags carried the story that China was tearing down the Great Wall

to demonstrate its openness to trade. The Times headline read, “Great

Chinese Wall Doomed! Peking Seeks World Trade!”

Newspapers worldwide picked up on the story. It was a real laugh –

until it reached the Chinese, who were furious upon hearing that the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers was coming to tear down their Great Wall. It was

the last straw for a secret group in Beijing already fed up with foreigners.

They attacked foreign embassies in Beijing, killed hundreds of missionaries,

and within months 12,000 foreign soldiers were in Beijing to stamp out

the short-lived Boxer Rebellion.

In Beijing’s outskirts, North of the Great Wall but still South

of the Siberian Ceiling, we were Floored at our discovery of rarely frequented

tourist sites such as the valley of petrified trees, which we found at

the end of 8 hours of winding roads and valleys.

Toy Ota on the Runway One stretch of road that angled

off to the left, in a narrow, secluded valley, looked remarkably broad

and straight, so I took it, hoping to find a shortcut through the maze

of mountains. I drove several hundred meters, amazed at how nice a road

the government had put up for such an out of the way place.

Then I noticed rows of Chinese Air Force jet fighters lined up on both

sides, covered with camouflaged netting. I slammed on the brakes, spun

about, and raced back the way we’d come. We drew stares but, fortunately,

no gunfire.

After too brief a week in Beijing, I asked several police if the roads

between Beijing and Mongolia were open to foreigners, and passable. They

looked surprised. “Of course they’re open. Not very good though.

Drive carefully.”

Thus armed with a semblance of official permission, we set off for Mongolia.

Return to top

"To know what is ahead, ask those

who are returning." Chinese proverb

"Be careful whom you ask." Bill Brown

Mongolian Time Machine

We shed centuries as we drove through villages and cattle towns, leaving

clouds of dust in our wake. Colorfully decked out Mongolian ponies were

hitched to every post. Corrals were packed with horses and cows, and auctioneers

dickered with buyers attired in Mongolian garb, replete with hats, high

black boots and daggers dangling from belts. Disney could not have done

it better.

We navigated plains and valleys and mountains, once stopping to talk to

a wizened old prospector, one of thousands of peasants panning for gold

in a riverbed just downstream from a state-run gold mining operation.

He eyed us suspiciously, but finally allowed us a furtive peek at the

tiny flecks of gold hidden in his thumb-sized Tiger Balm tin, and then

he turned his attention back to his beloved pan of mud.

An interesting but exhausting 15 hour day of driving brought us to the

Inner Mongolian capital of Hohhot. We were tired, dirty, and disillusioned,

and the surly attitudes of hotel officials confirmed our desire to get

out of Mongolia as quickly as we had gotten in. But once we escaped the

tourist traps, fascination won out over fatigue. We chatted with the friendly

Mongolians and Han Chinese we met on the streets, in shops, and in the

small, clean, family restaurant where we ate an interesting mix of Mongolian

mutton and noodles, and Chinese stir fried vegetables and rice.

In the evenings, we strolled through the park and watched parents playing

with their children, couples stargazing with telescopes, and elderly lovers

dancing to the music of a lively Mongolian band.

We left Hohhot in a much better frame of mind and body, and we determined

to avoid allowing the frustrations and fatigue of our stressful journey

to warp our impressions of people and places. We were, once again, in

love with China – for about half a day.

Return to top

Now a crucial decision: head West into the barren, hostile terrain of

West Mongolia and the Gobi Desert, or return to Beijing and Big Macs?

I surveyed both police and Mongolian truckers about the next stretch of

road: under construction? bandit-infested? (illegal bandits, not the legal

toll booth bandits). I also asked if it were open to foreigners, though

in all of China, no authorities ever hindered us in any way (except those

in Fujian Province, who had forbidden us to make the trip, but given the

dangers we encountered, we came to appreciate their concern for our safety,

and respected them for taking a stand).

From Hohhot we headed West to Baotou, heeding warnings that we never drive

at night unless in a convoy. We were also warned about Mongolian bandits

near Baotou. Armed with dogs and Russian rifles, they prey on unwary travelers.

But we made it through Baotou with only a minor encounter with an ineffectual

wannabe thief, and we spent the night in Dongsheng, just north of Genghis

Khan’s mausoleum.

Our 6 year old China guide book warned that local officials were suspicious

of foreigners, but from the friendly reception of locals on the street,

we suspected the book was out of date. It was not.

While the rest of China seems to have opened up to foreigners, Dongsheng

officials are as suspicious as ever. The hotel staff photocopied our residence

permits and then refused to return the originals. Then a security official

curtly ordered me to fill out the forms again. He took the second set

of forms and returned a full hour later and demanded that I fill out yet

another set of forms for the boys, which I refused to do unless they returned

our I.D.s. I also told him, politely of course, that Dongsheng had not

changed one iota since the China guidebook had blasted them six years

earlier.

Return to top

That evening, our pretty hotel waitresses tried to make amends by giving

the boys two complimentary cans of fruit juice, and I photographed them

with the boys, promising to mail copies. The ice was broken until I created

a cold front by asking the statuesque beauty who looked like a Chinese

Linda Carter, "Are you Mongolian?”

“Of course not!” she exclaimed huffily. “I am Han Chinese!”

And she flicked her long hair over her shoulder and stalked off.

"Two roads diverged in a desert,

and I -- I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the mess." Dr. Bill

Gobi Desert Sand Traps and Khan

Artists The next morning, after a brief tour of Ghengis Khan’s

mausoleum and museum, we blissfully headed south, descending into one

of the most savage, desolate, regions on earth -- a paradise for the robber

bands who have infested the desert for centuries, exacting tribute from

caravans and, as luck would have it, Toy Ota vans.

The road rapidly deteriorated from crumbly asphalt to gravel to dirt to

sand – deep, soft, and piled up on both sides, so high that there

was no hope of turning around, much less backing up. The wheels plowed

deeper and deeper into a white sea of dunes that shifted and crawled like

Mojave side-winders. How I wished for a four wheel drive. Or better yet,

wings.

“Bill, are you sure this is the road?”

“Sue, the hotel clerk said it was, and two truckers confirmed it.

The only other road is a 200 km detour. This should not take long.”

An hour later, the road was but a faint trail through the dunes. “Are

we still headed south, Shannon?”

The van was bouncing like a yo-yo as Shannon struggled to get a fix on

the compass. He eventually said, “Yes, dad. Sort of.”

The July desert sun reflected off the shifting white dunes, baking my

brain and my eyeballs, but the grinning bleached skulls of nameless creatures

warned me of our fate if I stopped. An hour later we saw a jeep approaching

through a cloud of dust – the second vehicle we’d seen in

4 hours. I flagged him down and asked if the road improved up ahead. The

driver grinned and the desert sun shone off two gold teeth. “Great

road!”

May the fleas of the Khan’s camels infest that Khan artist’s

armpits.

Return to top

Hour after hour, we plowed deeper into a sterile wasteland that was so

still the very earth had ceased to breathe. I began to imagine movement

in the dunes and the crevices. Every time I crested a dune I prayed for

green and was rewarded with white – row upon row of dunes stretching

infinitely into the distance, and I could see why Chinese see white as

a symbol not of purity but of death. I felt, not for the first time in

China, trapped in a Twilight Zone set, traversing an infinite desert of

despondency.

To avoid sinking into the powder I plowed as fast as possible over the

bone-jarring path, over and around dunes, until we sank to our axles in

a dune that was so high and loose it did not seem natural. And it wasn’t.

On many steep ascents, we had passed makeshift road barriers erected by

desert robber bands committed to relieving unwary drivers of the burden

of excess cash. I had determined to crash any closed gates, but not even

Arnold Palmer would have been prepared for this Gobi desert sand trap.

I could not slow down, or back up, so Toy Ota plowed in up to her axles

in the suspicious mound of sand.

Our spirits sank faster than our tires. It was the middle of the blazing

Gobi desert, in July, and not a soul in sight--until we slogged to a halt,

whereupon a dozen souls popped out of the sand like Jacks in the Desert.

Stuck vehicles were their stock in trade. And knowing something of the

history of Gobi desert robbers, I was not entirely relieved to make their

acquaintance.

Return to top

Dambin Jansang, The Avenger Lama

The name of Dambin Jansang, the “Avenger Lama,” still strikes

terror into the hearts of elderly desert dwellers who believe that he

yet lives. A master of disguises, Dambin never allowed those around him

to know where his actual dwelling was, and some believe that even if he

is dead, his spirit still haunts the wastelands.

A Western Mongolian born in Russia, his revolutionary activities landed

him in a Russian prison early on, but he escaped and fled to Tibet, where

he studied Buddhist metaphysics and Tantric mysticism.

In 1900, he returned home, claiming to be the reincarnation of Amursana.

Mongolians whispered excitedly around their campfires that the new god

would unite them to create a new Mongolian nation, and in 1911, Dambin

led the Mongols in an attack against the Chinese garrison of Kobdo. After

taking the town, he slaughtered every Chinese and Moslem inhabitant, and

personally performed a ritualistic murder of ten people, smearing their

blood on the troops’ standards as a sign of victory.

When Cossacks captured him in 1914, they found his seats in his tent covered

with the hides of his two enemies whom he had skinned alive. He was imprisoned,

released again, and eventually murdered by Baldan Dorje, a Mongolian chief

who stabbed him, then strode out of his tent and, to the robbers’

horror, swallowed Dambin Jansang’s bloody heart, which supposedly

made him invincible. When he attacked a supposedly impregnable fortress,

the entire enemy garrison simply fled in terror.

Baldin Dorje impaled Dambin Jansang’s head on a stake and paraded

it throughout Mongolia, but many refused to believe Dambin was dead. I

suspect he now shares a condo in Calcutta with Elvis.

Return to top

Exhumed As Dambin Jansang’s

descendants surrounded us, I wiggled out from underneath the van where

I had been lying in the baking sand trying to extricate us with a small

hand trowel - a great implement for beach play but less than adequate

for major excavations.

“What’s up?” they asked in Mongolian accented Mandarin.

“Oh, diggin’ a hole to the States,” I said, borrowing

Shannon’s line.

They didn’t laugh. They gawked at my blond hair and beard and asked

if I was Chinese.

“I live in China,” I answered.

One of them knelt to get a better look at me. On this broiling summer

day, he wore cast off military fatigues over 3 or 4 layers of other cast

off clothing, and a blue cotton sweat suit under all that. Just the sight

of him made me sweat. His hair was long and unkempt and dangled over one

eye, making up for the eye patch that any decent pirate of the desert

would keep in his kit. His dark eyes peered at me from the shadows of

his blue Mao cap, which he wore at a rakish angle. He favored me with

a lopsided grin; he had 3 gold teeth, but he had to curl his lip worse

than Elvis to display them to full advantage, especially the tooth tucked

to the right. He sized me up, then said, “You need some help?”

“Naw, I’ll manage.” And I smiled, and I hoped they would

not try to open the van, where Sue and the boys were cringing inside.

“It will take a long time to dig out with that spoon.”

“It’s not a spoon, it’s a trowel. And I’m in no

hurry.”

“We’ll push you out for 50 yuan.”

Seven dollars was not a big price to save our four lives, but I also knew

they’d deliberately set the trap, and I did not want to give in

too easily, lest they suspect we were loaded. And I remembered the Chinese

pastor’s advice:

“Never show fear before the pack.” I smiled and said, “Too

expensive! I’ll give you 20 yuan.”

The man said, “Done!” He gave me an enigmatic smile, then

signaled his band of cohorts, who waded through the sand and took up their

positions behind the van. As I climbed into the driver’s seat and

shifted the van into neutral, I thought, “They sure aren’t

much at bargaining.”

A heave and a ho and we were exhumed from our sandy tomb and we sailed

over the top of the dune – and sank right into the twin of the dune

behind us. Before the dust had settled our rescuers were at the door,

grinning. Gold Tooth said, “And now, friend, the remaining 30 yuan?”

“Are there any more dunes after this one?” I asked suspiciously.

“No, no!” He held his hand up, as if swearing on the Koran,

and said, “There are only these two!”

I believed him, and when I laughed, the whole band burst into laughter.

I paid the 30 yuan, and he thanked me, and winked. I half expected him

to doff his cap and bow, for in spite of his rags he carried himself with

style, like a Mongolian version of Errol Flynn, that gallant swashbuckler

of the silver screen. My account settled, they once again demonstrated

their prowess and I sailed off down the desert, thanking them and their

ancestors and praying I’d not need their services again.

Return to top

By now the van’s interior was a shambles. Shaken and bounced like

Dorothy and Toto in a Taiwanese twister, our shelves had collapsed, food

containers had burst open, and all three of my passengers were in tears,

wishing they were in Kansas or Oz or anywhere but Mongolia. I too had

had more than my share of sand.

I always fancied that I shared the Arab’s serene love of the desert.

I’ve watched Peter O’Toole’s Lawrence of Arabia 4 times,

and I’ve pored over back issues of dog-eared Arizona Highways. I’ve

even driven through Death Valley and serenely contemplated its lethal

loveliness --but always from the comfort of an air conditioned car, on

a smooth blacktop, with call phones every 10 miles, and gas stations and

fast food outlets. Security is the seed of serenity, and now we had neither,

as I wrested creaking Toy Ota through the sadistic sands of the Gobi.

My wife and small sons clung to each other in the back, eyes squeezed

shut, and the gas gauge flirted with empty, and there was no greenery

or people or even road in sight, and I felt not serenity but despair.

“We’re almost there!” I shouted to my three passengers,

but I had no idea just exactly where there was, or in what direction to

find it. The sun was to my right most of the time, but the path curved

and twisted back upon itself so often that I had a sinking feeling we

were headed more West than South – not cutting across the desert

but plowing further into a wasteland that modern Chinese researchers brave

only in camel caravans.

I was gripping the steering wheel so tightly that my knuckles were whiter

than my wife’s face when I rounded a sand dune and saw – a

row of trees! People!

Dusty peasants walking behind dusty mules gawked as we emerged triumphantly

from the desert in a glorious cloud of dust and barreled onto the most

beautiful dirt path I had ever seen in my life. And 30 or 40 kilometers

further we reached the southern end of the 200 km detour that we discovered,

far too late, locals take to avoid the 50 km shortcut we had barely survived.

Return to top

The Not So Great Wall

As we entered Shaanxi province, we saw rising up on the distant horizon

what resembled a massive Mesopotamian ziggurat. (Wrong turn somewhere!).

Closer inspection revealed it was a castle or tower, decked out with flags

like Disneyland or a real estate promotion in the Southern Californian

desert. The structure looked new, but we checked our maps and found it

was the recently refurbished but ancient Zhenbei tower, part of the Great

Wall that cuts across Yulin County. As we drove through the pass in the

Great Wall, we heaved a collective sigh of relief as we officially left

the barbarian desert behind us.

That was the last time we saw the Great Wall, which continued its lonely

vigil all the way to Jiayuguan pass in Qinghai, where the rubble that

remains is half buried in sand dunes. I think of the millions who died

building it, and its present state. It brings to mind Shelley’s

Ozymandias. Fully 700 years before the Chinese began the Great Wall, the

Egyptians erected the funerary temple of Ramses II (a.k.a. Ozymandias,

1279-1213 B.C) on the west bank of the Nile River at Thebes in Upper Egypt.

The temple boasted a 57 feet tall seated statue of Ramses II – a

work designed to preserve his greatness for eternity. In 1819 Shelley

wrote of the shattered work,

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Most of the Great Wall is now but a colossal

wreck, boundless and bare, and the lone and level sands stretch far away.

Except, of course, for the Disneyesque tourist attractions north of Beijing

and in Yulin County, Shaanxi.

Vanity of vanities, all is vanity. So why on earth was I dragging my wife

and 6 and 8 year old sons on a 40,000 kilometer nightmare drive around

China? Curiosity? To know China? Vanity? Sir Edmund Percival Hillary claimed

that he climbed Everest, “Because it was there.”

Perhaps we drove around China because it was there. More likely, it was

a Descartian attempt to prove I am here, though perhaps it only proves

I am not altogether there. But who is?

Return to top

Shaanxi Hobbits “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.” (The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien).

We most gladly left the Gobi desert behind

us, for a while anyway, and descended into a deep, narrow, twisting valley.

The steep, loess cliffs towering on either side were riddled with manmade

caves from top to bottom, because Shaanxi locals are hardcore Chinese

Hobbits.

Shanxi cave dwellings are actually quite practical. They are warm in winter,

cool in summer, and safe. While the poorest make do with simple holes

and pounded clay kangs (heated platform beds) and tables, the better off

burrows boast beautiful carved wooden doors and intricate lattice windows.

Even the well-to-dos’ homes have rounded ceilings and turfed roofs

to preserve the ambience of a holeish habitat.

I can imagine a Shanxi cave dweller, in his sheepskin coat and “white

sheep’s belly towel” wrapped about his head, praising a neighbor,

“Your home is so cozy.”

“Oh, it’s just a hole in the wall.”

Rich or poor, most cave dwellers boast one multi-purpose piece of furniture

– the kang, a large block of mud bricks or stone slabs with a passage

underneath so that left-over heat from the cooking fire can warm the kang

before going out the chimney. The energy efficient kang saves firewood,

keeps the air fresh, and serves as a warm bed, couch, sewing center, desk

for small scholars to do homework, and a place to entertain visitors.

Most cave dwellers are poor, but happy and hospitable, offering even the

most casual strangers a place on the family kang, and bowls of fresh apples,

and peanuts, and wine-saturated dates – a local specialty, which

are not only tasty but also supposedly improve spleen and kidney functions.

The dates are dried and sacked to use through the winter or to give to

friends and relatives, or for weddings and elderly people’s birthdays.

Return to top

Cave dwellings’ doors and windows reach right to the ceiling, insuring

maximum illumination. Walls are plastered with the bright 20 cent posters

sold in bookstores throughout China – pictures of Mao, Zhou Enlai,

the Monkey King, Mickey Mouse. They also paste up ‘lucky’

slogans such as “Wealth” and “Long Life.” Windows

and doors are decorated with intricate paper cuts snipped away by the

women on long winter evenings. Even small girls spend hours with scissors

and paper, practicing the ancient art, for in this area of the country

two of the most important qualities of a bride should be skill in embroidery

and paper cutting. I’ve often though Susan should take it up, for

she too is a real cut up.

Caves aren’t bad homes. They are inexpensive, durable, comfortable,

climactically controlled, and make ecological as well as aesthetic sense.

Since they are built inside cliffs, they don’t occupy farmland,

or hurt the environment. Farmers also use caves for granaries, sometimes

having a separate cave for wheat, sorghum, corn and millet.

Above all, caves are durable. General Xue Rengui’s cave is still

livable after 1,300 years, suggesting that sometimes the old ways are

indeed the best ways.

I used to think it silly for Englishmen to roof their cottages with straw,

but a good thatched roof can last decades, and the seaweed roofed homes

in Shandong province can hold up an entire century. But our ‘modern’

American roofs need replacing every ten or fifteen years (though America’s

economy is built on planned obsolescence, not stewardship of our planet).

After an excruciatingly long drive, we pulled into Yan’an at midnight.

It was here that the Great Helmsman himself holed up in a cave after the

6,000 mile Long March in 1934. It was inspiring, yes, but we opted to

hole up in the guesthouse, where we slept the sleep of those who had almost

been dead. And next morning, well rested, we drove on to Xi’an,

the ancient gateway to the not so silky Silk Road.

Return to top

The Not so Silky Road

In Xi’an, we recuperated for a full week in the Jiaotong University

guesthouse, crawling forth only a few times to walk atop the city’s

ancient, massive walls, which impressed me more than the obligatory tourist

site housing the unearthed Terra Cotta warriors. After all, I had hundreds

of green plastic soldiers as a child. The Emperor simply had more money

for bigger toys.

After our Xi’an R&R, we set off down the ancient Silk Road towards

the arid heights of Gansu and Qinghai. The road was not as silky as I

had expected. As we made our way along rough dirt roads that clung to

mountain peaks tighter than a hangman’s noose, it was hard to imagine

that this trade route had been in use for 2,000 years.

During the first century A.D., 2,000 camels a day carried silk to the

Chinese border. The Emperor protected the culture from contamination by

forbidding barbarians to enter, and by forbidding Chinese to leave. It

was much like today’s policies.

The resourceful Chinese merchants left their silk goods, with the expected

price marked clearly, on the roadside just outside the furthest walled

city. After they beat a hasty retreat, the foreign traders rode up, took

the silk, and left the required amount of coral, rubies, wood, copper,

tin and barrels of honey. Only after the barbarians had departed did the

wary Chinese retrieve the Westerners’ wares.

China, determined to protect her intellectual property rights, absolutely

forbade the export of raw silk, and its origin was a mystery until 550

A.D., when two Persian Nestorian monks smuggled out silkworm eggs concealed

in bamboo. They presented the eggs to the Emperor Justinian at Byzantium,

and the cat was out of the bag. And Justinian never paid China a penny

in royalties.

The silk road’s history is endlessly fascinating, but my dwellings

on the past vanished as the precarious present reared its ugly head at

me.

Return to top

Toy Ota Gives up the Ghost

Forewarned of Ningxia’s poverty by comrades, police and National

Geographic articles, we weren’t surprised at the poor roads, or

at the mendicants lining the road selling squirrels on strings to passing

truckers. But we also saw construction at virtually every turn. The children’s

laughter and the ready smiles of their parents suggested they were far

from helpless or hopeless. Their courage in poverty strengthened my respect

for them and reinforced my own sense of responsibility to help them.

But as I cerebrated upon these lofty hopes my own hopes abandoned me.

In this remotest, poorest area of China, on a deserted mountain road,

in the dead of a moonless night, Toy Ota gave up the ghost.

I coasted backwards to the bottom of the mountain, where to my surprise

I discovered, only 5 meters from where the van had rolled to a stop, a

sign: “Vehicle repair!”

How true the Greek proverb, “When God throws, the dice are loaded.”

An old grandpa smiled at us, donned his worn coat, crawled under the van

and announced that our entire fuel system was clogged up from filthy fuel.

Though lacking tools and parts, he managed to clear the lines enough for

us to sputter another 6 hours up the mountains to Lanzhou, Gansu Province’s

capital, and the transportation hub of the Northwest.

We checked our ailing van in to the Lanzhou Toyota repair center, and

checked ourselves in to the Lanzhou Hotel, where we enjoyed a panoramic

view from the alcove of our 21st floor room. Even the 10 p.m. blackout

did not dampen our spirits. The boys perched on the ledge counting cabooses

in the train station far below, and mom and dad watched their boys. Who

needs television when you have children?

Next morning, the power was still out, and so were the elevators, and

the front desk was strategically ignoring calls. So I traipsed briskly

down 21 flights of stairs, filled my red plastic waste bucket from the

fountain, and walked not so lightly, bucket of water on my shoulder, back

up the 21 flights.

Then I descended, a tad more slowly, the 21 flights of stairs. I retrieved

Toy Ota from the Toy Ota repair shop, where I was charged double what

they’d quoted. I returned to the hotel and crawled painfully back

up the 21 flights of stairs to collect Sue, the boys, and our three heavy

suitcases and giant water container. After staggering down the 21 flights

of stairs, I loaded the van and left Lanzhou’s 3-Star hotel, resolving

that next time I’d book the basement.

The fiascoes in the Mongolian desert and Ningxia mountains had taken a

toll on my health, and 21 flights of stairs, five times, finished me off.

Thank heaven for Xining.

Xining,

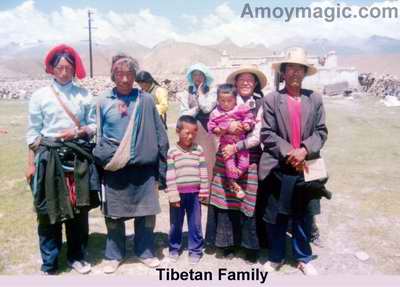

Qinghai’s capital, is a natural sanatorium. This two mile high city,

perched on the edge of the 4-5,000 meter Qinghai plateau, is crisply cool

and clean, and the people are a fascinating, friendly mix of cultures.

The several mosques suggested Muslims were the majority, but we also saw

a large new Christian church, and we even encountered our first Tibetans

in their striking costumes and jewelry.

Xining,

Qinghai’s capital, is a natural sanatorium. This two mile high city,

perched on the edge of the 4-5,000 meter Qinghai plateau, is crisply cool

and clean, and the people are a fascinating, friendly mix of cultures.

The several mosques suggested Muslims were the majority, but we also saw

a large new Christian church, and we even encountered our first Tibetans

in their striking costumes and jewelry.

The dorm-style rooms of the Xining Guest House were plain but inexpensive

and clean, and boasted hot baths; I took two the first evening.

Xining’s unpretentious, no-star guesthouse, and its warm, cooperative

staff, rate 5 stars in my book any day.

Return to top

The World’s Highest Highway

Xining is two miles high, but the road west ascended higher yet, laboriously

insinuating itself into forbidden ranges. Verdant valleys flung between

the precipitous peaks were dotted with Mongolian yurts and colorful Tibetan

tents perched precariously on hillsides so steep that Susan wondered how

they slept on sloped floors.

Shiny new Suzukis and Hondas were parked beside some of the yurts, but

they’ll never match the horse. With bated breath we watched horsemen

on mounts as sure-footed as mountain goats zigzag up sheer cliffs, driving

cattle and shaggy yaks up their perpendicular pasture.

As we approached our first 4,000 meter pass, my head throbbed and my lungs

labored; one week later we would long nostalgically for 4,000 meters lowlands.

But misery loves company, and battered “Liberation” trucks

wheezed and gasped worse than I did. They inched up the steep grades,

hoods raised to force as much of the rarified air as possible onto the

overheated, sputtering engines. With the hood up the drivers drove blindly,

so their partner leaned out the side shouting directions to keep them

on the narrow road chiseled into the cliffs. Some places were not wide

enough for vehicles to pass, though some must have tried, judging from

the carnage at the bottom of the 1,000 foot cliffs.

I was anxious to put these mountains behind me, but too soon the mountains

and the grasslands gave way to salt flats and desert embracing the widest

horizon I had ever seen. I pitied the poor nomad with a fear of widths.

Ships

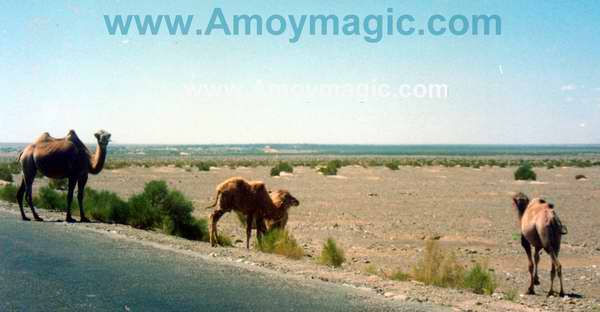

of the Desert Occasionally the monotony of this tedious terrain

was interrupted by herds of camels, some unattended and others driven

by herdsmen whooping like warring Arabs. One camel lagged far behind the

others, and I suspected he would soon find repose in a rectangular tin

of the “Chili Camel Meat” (Mongolian luncheon meat) like we

had bought as a souvenir in Xining.

Ships

of the Desert Occasionally the monotony of this tedious terrain

was interrupted by herds of camels, some unattended and others driven

by herdsmen whooping like warring Arabs. One camel lagged far behind the

others, and I suspected he would soon find repose in a rectangular tin

of the “Chili Camel Meat” (Mongolian luncheon meat) like we

had bought as a souvenir in Xining.

Return to top

Back when Christ walked the Judean deserts, these “ships of the

desert” (Chinese call them this as well) were traveling the ancient

Silk Road, transporting Chinese silk, steel, pottery, porcelain, and tea,

and bringing back from Europe and the Middle East the pears, medicines

and perfumes prized by Chinese nobility.

Trucks have pretty much obsolesced camels, but a few ‘camel families’

remain scattered about the desert. In addition to providing camel wool

and milk, camels transport local medicines and furs to Mongolia, and they

return with tea and sugar and cloth. Caravans also make the three month,

3,000 kilometer trip to Xinjiang, though never in the summer, and travel

is always in late afternoon or at night, for contrary to popular belief,

camels cannot survive intense heat for very long.

For ten days before the caravan sets out, camels are denied water, and

their grazing is limited. Just prior to departure, they are given their

fill – as much as 100 kilograms of water at once, after which they

can travel two to three weeks without a refill.

Camel drivers sport fashionable, full length camel-hair coats, white on

one side and dark on the other. In the daytime, the white fur reflects

the sun and keeps them cool. At night, the fur is turned to the inside,

and keeps them warm.

Several times we stopped as herds of ten feet high camels wandered slowly,

stately, across the highway, the camel bells ringing monotonously. In

the vast stillness of the desert, the bells can be heard for well over

a mile.

Camel bells have always fascinated Chinese poets and musicians. The bells

are large, like a small bucket, and clang loudly each time the camel takes

a step. Legend has it that the bells keep the camel drivers from getting

lonely, as they sing songs to their rhythmic accompaniment. Less poetic

souls argue that the bells are just to keep the camels from getting lost.

Camel drivers can be sound asleep on the lead camel, but the minute the

bell on the rear camel stops ringing (only one bell per caravan), they

know a camel is lost. But when entering bandit-infested regions, camel

drivers turn the bell upside down, and the camels know to proceed quietly

until past danger.

Return to top

When Seeing Is Not Believing We soon put camel country behind

us and continued down the broad, flat highway, which shimmered and rippled

under the deadly rays of the desert sun. Several times we saw lakes, some

with trees lining them, stretching across the horizon ahead of us or on

both sides. “Those are mirages, boys,” I said.

“They aren’t really there.”

“No way.” Susan protested. As we neared a large lake, surrounded

by trees, she said, “That one has to be real, Bill. It has trees.”

On cue, the oasis shimmered and dissolved into sand and stone, and my

shocked sweetheart said, “That is weird.”

We ached for real greenery as we traversed terrain beside which the Mojave

Desert was lush by comparison. And we found it.

Several times we crested bare peaks of stone and sand to discover shimmering

emeralds coruscating in the desolation below us. Dozens of predominately

Muslim towns sprang right out of the deadly desert. Their small streets

were shaded with trees, and the desert around them had been transformed

into great fields of grain, which stood like rank upon rank of green-clad

soldiers, defying the savage ascendancy of sand ready to leach their tenuous

lives should life-giving wells falter.

There is no ambiguity on the rarefied heights of the roof of the world.

As life duels daily with death, so light wars with darkness, and heat

with cold. Direct sunlight is blinding and blistering, but shadows are

dark and chilling. It was unnerving. We either sizzled in the sun or we

shivered as the most wispy of clouds passing overhead cast amorphous ebony

shades that crept like giant amoebas across the sun bleached rocks and

dunes, chilling us and, in passing, relegating us once again to the frying

pan. But a more chilling specter was the red light flashing on the gasoline

gauge.

Return to top

What A Gas! Sophisticated,

computerized gas stations are a dime a dozen in most of China. My favorite

is a Fuzhou station designed to look like the U.S. Space Shuttle, and

covered with hundreds of the glossy white ceramic bathroom tiles that

grace the exterior walls of everything from individual homes to multi-story

office buildings. NASA spent millions and couldn’t keep their shuttle’s

ceramic tiles from falling off. They should have used 15-cent Chinese

bathroom tiles.

But gas is at a premium in West China. Toy Ota was running on fumes by

the time we discovered a ramshackle, corrugated tin hut that served as

the only filling station for hundreds of kilometers. I hand pumped petrol

from a rusty barrel into a rustier bucket, and sloshed it into our tank,

soaking the ground and myself in the process – while half a dozen

curious Muslims anxious to meet Mohammed face to face huddled around me

with lit cigarettes in hand. I wanted to shed a little light on safety,

but I feared they’d light me instead.

I also filled two plastic containers with extra petrol – a dangerous

expedient, but less dangerous than being stranded on Qinghai’s permafrost

plateau. After we’d ascended in altitude a few hundred meters more,

the containers began swelling dangerously and the van filled with fumes.

Thereafter, I loosened the caps periodically, relieving the containers

but asphyxiating the passengers and driver.

Return to top

Hero Drivers The Qinghai

desert was an arid and lifeless plain, vast salt flats below and barren,

rocky peaks around us. The deep blue vault not far overhead silhouetted

the shreds of clouds that escaped from Tibet in the south, where low hanging

cumulus seemed eldritch extensions of the snow-capped ranges below. I

saw why ‘cloud’ came from the Old English ‘clud’,

which meant ‘rock’ or ‘hill.’ At times the clouds

resembled mountains, and at others the mountains masqueraded as clouds,

and the thought of driving Toy Ota into that uncanny realm through 3 mile

high mountain passes was alternately tonic and terrifying, especially

as the gas gauge once again whispered, “Feed me, Seymour.”

Perhaps I was not the only driver intoxicated with the hypnotic beauty

of these Himalayan heights. Traffic was virtually nonexistent, yet we

still passed at least a half dozen overturned, crushed trucks, some with

bodies laid out neatly beside the crushed hulks - a rite performed, no

doubt, by wandering Tibetan herdsman who had stumbled upon the deceased

hero drivers.

In every corner of the country, signs warn, “Don’t Drive Like

a “Hero!” (i.e., “Don’t play chicken”),

but even with trucks, cars and buses flung across the landscape like giant

matchbox cars, drivers act as though immortal. They barrel along 90 to

nothing down the middle of the road, even around blind, hairpin mountain

curves. But I was soon forced to do the same.

To give way too soon to oncoming traffic is seen not as courtesy but weakness.

The first few times I tried it I was nearly run off the road by buses

or logging trucks that came so close that one smashed my sideview mirror.

In Sichuan, a military truck driver, who evidently had missed out on the

“Army Loves the People” seminars in the spring of ‘89,

ran me right into a rice paddy.

I read the writing on the oncoming bumpers and realized that this was

not about playing hero cars, this was about survival. Fine enough. I had

offensive driving in the military, where we learned J-turns and all the

other maneuvers for protective operations and counter-terrorist situations,

and this was terrorism. I too took to the middle of the road, giving way

only enough to avoid getting slapped in the face by truckers’ reinforced,

telescoping side view mirrors, which are their equivalent of the disabling

razor edge projections on Ben Hur’s chariot. I was never run off

the road again.

One Night Stands It was midnight when we pulled in to

Golmud, the commercial and transport link between Tibet and the rest of

China. We hoped to spend two nights before crossing the lofty Kunlun and

Tanggula ranges into Tibet, but the hotel clerk said, “One night

only.”

At dawn, we purchased two bags of oxygen from a medical supply and headed

for the Golmud check post--with no little trepidation, having been forewarned

we might be turned back from the heavily guarded road.

Three youthful guards sauntered out of their shack and stopped dead in

their tracks, staring in disbelief. Never had a family of foreigners shown

up unescorted on the roof of the world’s doorstep in a Fujian van.

For weeks I had dreaded the Golmud check post, for foreigners are forbidden

to take even public ground transportation into Tibet, much less to drive

by themselves. But my worries were groundless. The guards examined my

driver’s license (like they would of a Chinese driver, but they

never asked for any further I.D.), and they asked a dozen questions, but

more out of friendly curiosity than suspicion. At long last they smiled,

wished us a safe journey, and lifted the red and white striped road barrier,

opening before us the last ascent to the roof of the world.

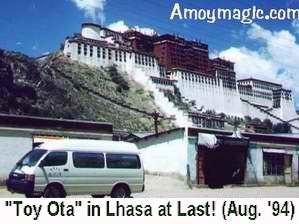

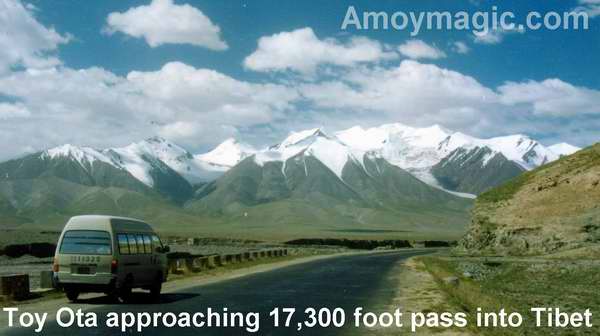

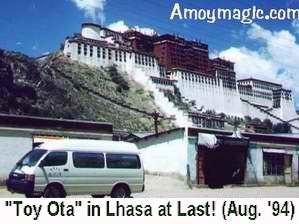

Lifeline The stretch from Golmud to Lhasa

was torturous but I won’t complain. It was a miracle they could

build it, much less maintain it. At 4,000 to 5,000 meters, this 1,166

km road is the world’s highest highway, at its lowest points still

not descending to America’s peak elevation. Rugged, otherworldly

terrain, scant oxygen, fierce winds, mammoth land slides, temperatures

that plummet to –30 degrees Celsius – it was a frigid realm

of ice and snow, inhabited by none but road workers.

Return to top

Until 1951, a journey from Lhasa to Sichuan took one year by yak. In fact,

Dr. David Woodward, who married Susan and I, reached the mountain stronghold

decades ago by horseback. He has tales to tell.

Tibet’s geographical isolation ended only in the 50’s, when

countless Chinese soldiers slaved, and perished, over the road that most

deserves to be called a highway, for there has never been a higher way.

Ever since their sacrifice, biting arctic-like winds and temperatures

have wreaked havoc on the permafrost foundation, threatening to send Tibet

back into its age-old isolation if the road crews miss a beat.

Every few kilometers, road workers toiled in rain and hail to preserve

this tenuous lifeline to the outside world, and virtually every worker

we passed smiled and waved at us, shouting in Mandarin and Tibetan. The

boys quickly picked up on the Tibetan greeting, “Tashee Deelay!”

Return to top

Deadly Detours With good infrastructure the key to economic

development, these good-natured, courageous road workers are the true

heroes of China’s modernization. But I was not enamored of their

devious detours, which lumbering Tibetan trucks had churned into pits

and quagmires worse than our Mongolian sand trap. Between the bouncing

and swerving, the high altitude sickness and carsickness, and the fumes

from the swelling plastic gas containers, even I, the driver, was sick.

After about 10 hours of stopping every few minutes for someone to bring

up their lunch, I proposed we throw up the towel as well and wait for

Tibet to come out on video. Susan clutched her olive drab, army surplus

canvas oxygen bag to her breast, and said, “We’ve come too

far now. Tibet or bust.”

I feared bust was more likely, but I laughed in spite of myself as her

words reminded me of a recent China Daily headlines, “Chinese bra

firm goes bust!” Kudos to that venerable publication’s resident

foreign experts, who probably agree with P.J. O’Rourke’s notion

that, “Seriousness is stupidity sent to college.”

Near dusk, we sidled up alongside a convoy of Tibetan trucks decked out

in brightly painted Tibetan swastikas and symbols. They were encircled

in a field beside the road, and the laughing truckers sat on rocks around

a blazing campfire. They look up only briefly, then turned their attention

back to their fire, as if a family of Californians in a Toy Ota were everyday

fare for them.

Return to top

Tibetan Convoy As Sue prepared for the three of them

to bed down in back, I leaned against the driver’s door and watched

the truckers lug out a four feet long wooden churn, which they primed

with butter, salt and tea, and took turns pumping with alacrity to produce

their favorite beverage. At dusk, they packed up their churn and remnants

of yak dung from their fire, and prepared not to bed down but to leave

– with us in tow.