![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

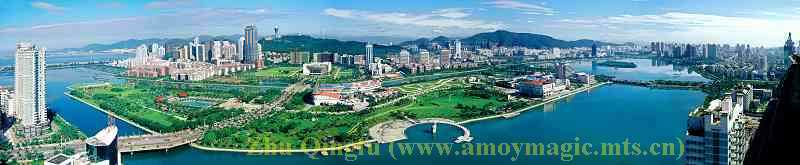

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

"Mad

About Mandarin!"

All about learning Chinese!

(by Dr. Bill Brown, Xiamen

University MBA Center)

Click Here for our Favorite

Fujian Destinations

"Mystic Quanzhou--City of Light"

"Discover Gulangyu"

Click Here for "Minnan Proverbs!"

Click Here to learn the origin of the name "Amoy"

“Translation is always a treason, and as a Ming

author observes, can at its best be only the reverse side of a brocade—all

the threads are there, but not the subtlety of color or design.”

...................................... Okakura,

The Book of Tea

If you’re staying in Xiamen awhile, I recommend

you try to pick up a little Mandarin. Xiamen University’s Overseas

Correspondence College offers full and part-time courses – or

hire a tutor (though the tutor route takes lots of discipline, and the

tutor may be more interested in learning English than teaching Chinese).

Foolproof Mandarin Courses? I’m

still hoping to get Mandarin down myself. Years before coming

to China, I took college Mandarin courses. I memorized stacks of flash

cards bought in Taipei and Los Angeles’ China Town. I tried the

course advertised in flight magazines – the one that promises native

level proficiency and a high post in the Diplomatic Corp within 90 days

or double your money back. In desperation, I even paid $500 per month

for a year of private tutoring, and a year later and $6,000 poorer could

barely tell our tutor zaijian (goodbye). Xiamen was my last hope. I could

just see those enigmatic squiggly characters coming to life – if

I could just survive the enigmatic enrolment.

Our college administrators had good hearts, but I suspected some were

but simple souls hauled in from the countryside and handed a pen, an official

chop and a blotter, and told to go manage—just like hundreds of

thousands of city folk were carted off to the countryside, handed a hoe,

and told to go farm; getting enrolled was certainly a long roe to how.

The administrator began day one of our beginner’s class by handing

out a pile of Chinese forms and explaining rapidly, in Chinese, that we

were to fill out the forms, in Chinese. When we just sat there, lost,

he said, “What is wrong? Please fill out the forms now.”

In my haltered Chinese I said, “Teacher, if we could already read

and write Chinese, we would not be in this beginner’s Chinese course.”

He stalked out and returned with a translator.

Shanghaid on Shibboleths

Not to worry. Chinese are exceptionally patient, and good humored. Just

talk with everyone you meet and you’ll pick it up eventually –

with a southern accent!

The Book of Judges (Bible) recounts how the Israelites found out who was

friend or foe by making them say Shibboleth. The foe could not pronounce

the “sh” and invariably said “Sibboleth.” And

lost their tongue and head with it.

Southern Chinese can’t pronounce “sh” either, so Shanghai

is Sanghai. They also can’t tell f from h, or l from r and n, or

the long e and the short e. To further complicate matters, they hear no

difference between t and th, or c and ch or z and zh, deng deng. And it

does make a difference, especially in business, because it is impossible

to tell “4” from “10” or “eat” (yes,

the tone is different, but they mix that up too).

If Southerners can’t get the sounds out in Chinese, it stands to

reason they trip over the same ones in English. No matter how hard most

Xiamen people try, my name “Bill” invariably comes out “Beer.”

One Christmas, my hapless Southern students threw in the towel and their

tongue and presented me with a Christmas card made out to, “Professor

Beer,” and a nicely wrapped bottle of Chinese Tsingdao beer (the

most enduring legacy of Germany’s occupation of Shandong Province

up North).

Inevitably, I too have acquired a slight Southern Chinese accent, to Northerners’

endless amusement. That’s why many Chinese experts recommend learning

the language in the North, but I’ll take a few shibboleths over

frostbite any day.

So, Ni Hao, y’all!

Back to Top

A Word’s Worth

1,000 Pictures I often preface proverbs with, “Confucius

said,” because it’s a safe bet that either he or some other

ancient Chinese did – and probably in 4 words or less.

Most of the planet says, “A picture is worth a 1,000 words,”

but for Chinese, a word may be worth a thousand pictures, for over the

aeons they have distilled their wisdom and experience into concise proverbs

that strike to the heart of any matter, and strike fear into the heart

of foreign language learners.

Even after memorizing the 3 to 4,000 characters of a minimal vocabulary,

we’ve no guarantee we have any idea what they mean when they are

used against us. No dictionary can convey the full nuances of a character,

and 3 or 4 strung together in one of China’s tens of thousands of

proverbs conjure up ancient historical incidents, or classic poems, or

paintings, or deep philosophical notions. My favorite ancient Chinese

book is “The Art of War,” which has influenced military, business,

and diplomacy—and the entire classic is only 5,000 characters. That’s

like fitting “War and Peace” between the covers of Dr. Seuss’s

“The Cat in the Hat.”

Chinese have a proverb for every occasion. A Chinese businessman who squanders

his capital “drains the pond to catch the fish.” A public

figure who thinks he can hide an immoral private life, “Covers his

own ears while stealing the bell.” Impatient people are “rice

pullers” -- like the foolish farmer who killed his rice plants when

he tugged on them to make them grow faster.

“Contradiction” in Chinese is maodun, or “spear-shield.”

It refers to the ancient fable of the weapon salesman who marketed both

impenetrable shields and unstoppable spears.” Inappropriate public

policies are like “using wood to put out a fire.” People with

unrealistic fears see, “a soldier in every tree and bush.”

A persistent person is like the old granny determined to “grind

an iron rod into a needle.” The fawning sycophant capitalizing on

others’ power is the “Fox exploiting the tiger’s prestige.”

Every saying makes a point, but also stirs up images of the story behind

it. Lao Tzu, founder of Taoism (The Way), used only 4 words to preach

an entire sermon on the power of gentleness and softness over inflexibility

and hardness. He said, “Teeth fall, tongue remains.” (hard

teeth fall out, soft tongue and gums remain into old age). Translation:

“Go with the flow!”

Back to Top

Drawn to Chinese I'm drawn to Chinese--perhaps

because I like drawing! And that's basically waht Chinese is--not writing

but drawing. And while the Chinese have a saying

or a solution for everything, they're often at a loss how to teach us

foreigners the ABCs of Chinese. That’s mainly because there aren’t

any ABCs. No alphabet at all—just 40 to 50,000 characters to memorize.

Drawn to Chinese I'm drawn to Chinese--perhaps

because I like drawing! And that's basically waht Chinese is--not writing

but drawing. And while the Chinese have a saying

or a solution for everything, they're often at a loss how to teach us

foreigners the ABCs of Chinese. That’s mainly because there aren’t

any ABCs. No alphabet at all—just 40 to 50,000 characters to memorize.

Chinese characters are pictographs—drawings

of objects or ideas. So in a sense, all literate Chinese are artists.

And pictographs have a great advantage over alphabets. They aren’t

abstract representations but concrete drawings, so any Chinese can ‘read’

their meaning, even though they are pronounced completely differently

in Cantonese, Sichuanese, Pekinese, deng deng. Even Japanese can read

them, for Japan’s language, like some her culture and religion,

evolved centuries ago from ancient China.

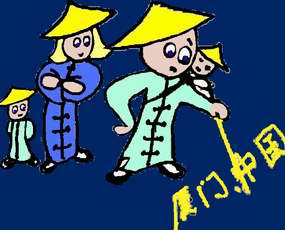

Some Chinese pictographs so closely resemble their object that even illiterate

foreign friends can figure them out. Consider the characters to the right:

Change is afoot

(Speaking of which, people ask, “Is there

a lot of change in China?” I answer, “None! Taxi drivers don’t

have change, stores don’t have change; postal clerks don’t

have change…)

Chinese characters are changing (both the written and the 2-legged kind).

After must post-Liberation deliberation, New China decided to fight illiteracy

by simplifying characters. For example, “hui” (meeting) was

simplified from 13 strokes to 6—much easier to memorize and to write.

But the art of simplification can go too far. On bus signs, for example,

“Xia,” (from Xiamen) is often written with three strokes instead

of twelve. Taken this far, simplification robs characters of much of their

beauty and meaning. Think of how we would react if Uncle Sam fought illiteracy

by simplifying English. How wud we lik it if our govurnmint

tride too improov literasee and speling bi geting rid ov awl unesesaree

leterz and xsepshuns in speling?

Back to Top

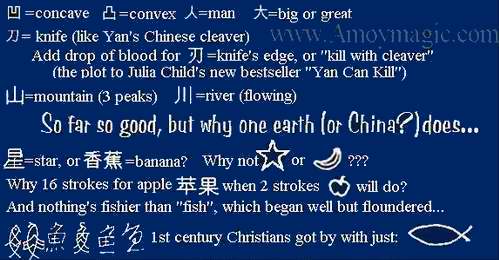

A Modest Proposal

Aesthetics aside, it was courageous of Beijing to tamper with the ancient

language of the most tradition-bound people on earth, and strike a mighty

blow against illiteracy. But illiteracy might be vanquished forever if

Beijing finished the job of simplification by using a few of my suggestions:

Ups and

................................of

Chinese!

.................Downs

To further brutalize us barbarians, Chinese tones play havoc with our

ears (see Dr. PinYin’s unPatented PinYin Guide at the end of this

chapter). Grammar and word order are different too. “Please buy

me a coke” becomes, in Chinese, “Please give me buy a coke.”

And Chinese change a sentence’s meaning, tense, or intensity by

tacking on little sounds like le, and ma, and ee, which is why Chinese

who speak English often say changee instead of change, and lookee instead

of look.

There is no end to the mistakes,

some quite embarrassing, that Chinese coaxes out of Americans. About a

century ago, an American missionary asked his Chinese maid to prepare

chicken for dinner. The maid returned 3 days later and said, “I’m

sorry, Pastor, but I couldn’t find anyone willing to marry a foreigner.”

“Chicken” sounds similar to “wife,” but even said

correctly in another context, “eating chicken” can mean dallying

with a prostitute, much to Colonel Sander’s dismay.

Back to Top

Left or Right? There’s also

the matter of knowing one’s left from one’s right. While English

is written from left to right, and Hebrew is written from right to left,

Chinese goes with the flow – left to right, or right to left, or

even top to bottom. All are equally acceptable. I’ve even seen diagonal

(but so far no bottom to top), and I’ve come across sentences going

two or three directions on the same page. Only by context do you know

the direction, and short sentences are a bear.

Xiamen Univ. is Everywhere!? I once

told a Chinese friend, “Xiamen University has buildings all over

China and Asia!" and I pointed to a sign with the two characters

for “Xiamen University.”

My friend laughed. “You’re reading it backwards!” Sure

enough, Xiamen University backwards was Dasha, or "hotel"

(from Russian “dacha”).

Excess of Courtesy is Discourtesy

............................. Chinese Proverb

Titled Gentleman

Even if you can talk to your Chinese friend, how do you address them?

Chinese honorifics are legion and lethal. Even common laborers have titles.

They are called “Master,” and they are, and they know it.

Try to get a carpenter who is just lumbering along to finish a job on

schedule and you’ll see just who is master in Socialist China.

Back to Top

Crying Uncle

I have at least 8 licit titles and a few I’d rather not discuss.

I have been called “Professor Pan,” “Teacher Pan,”

“Master Pan” and “Mr. Pan.” My Chinese elders

may call me Xiao Pan (Xiao means little, or young), but people younger

than me say Lao Pan (Lao is old, or venerable). Some Chinese children

like to call me uncle—but which kind of uncle? I’m either

Bobo or Shushu, depending on whether I am older or younger than the child’s

father. When the child doesn’t know an elder’s age, then he

really cries uncle.

But it all Pans out in the end.

Besides, aunties and uncles are on their way out, thanks to the one child

policy. With no aunts and uncles and nieces and nephews, traditional family

structures are undergoing greater simplification than the language. Happily,

in my wife’s home I use only two titles: “son”, and

“your highness.”

But in all seriousness (wow!), Mandarin is a beautiful language, and spending a little time on it will make your stay a lot more pleasant and profitable.

Dictionaries, Diction, and Deng Deng

Whether you master Mandarin or not, a good phrasebook and dictionary are

essential. The absolutely best dictionary around is Oxford University

Press’s “Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary.”

It is one of the very few that use Pinyin throughout, so you can make

a semblance of pronouncing those pictographs—and so you can look

both English and Chinese words up alphabetically. Otherwise, given that

Chinese doesn’t have an alphabet, how do you look things up? You

can use pinyin, but if you don’t know the character, then you can’t

even pronounce it to spell out the pinyin.

Back to Top

Different Strokes for Different Folks

There are several methods of searching Chinese dictionaries, but none

are foolproof, even for Chinese. Some arrange by number of strokes: characters

with 1 stroke, 2 strokes, ? strokes, ? strokes, ? strokes, deng deng.

This is broken down further (and I do mean broken) by arranging them according

to which stroke is first (vertical, horizontal, slanting down and left,

or up to the right, deng deng). But I’ve come across characters

that even Chinese professors could not find in this way. One professor

who was a real character rifled the pages of my dictionary for 15 minutes,

then said, “It’s no problem looking this up because we know

it anyway.”

Well, different strokes for different folks.

The little red Oxford Dictionary is found in most mainland bookstores.

“A Chinese-English

Dictionary,” produced by Beijing’s Foreign

Language Institute, is another excellent tool—and plain fun to read!

I read it through twice in four months just because I enjoyed the sample

English sentences! Bear in mind, of course, that it was printed in 1988—scarcely

a decade after the unCultural Revolution, so it’s not surprising

that every sentence had a revolutionary bent.

My favorites "sample English sentences"

include:

Suppose: "I suppose she’s gone

to practice grenade throwing again." (what a hot date she'd make!)

Anew, afresh: "Launch a fresh offensive!"

Barely: "When I joined the 8th Army

route, I was barely the height of a rifle."

Be: "I want to be a PLA man when I grow

up."

Armed with such a vocabulary, imagine the conversations students strike up at Friday night English Corners! ( But jesting aside, it’s a very comprehensive little dictionary).

Mandarin Chinese—a marvelous language!

And it would behoove you to learn a little. After all, it’s

the official language of 1/5 of the planet’s people. But if 40,000

pictographic characters intimidate you, start with China’s official

romanization scheme, PinYin. It’s simple, and useful—and I

tell you how in “Dr. Bill’s unPatented PinYin Guide.”

Back to Top

Dr. Bill’s unPatented

Pinyin Guide

(from Amoy Magic--Guide to Xiamen and Fujian,

p.391)

Make the magic of Amoy come alive by spending a few minutes

mastering China’s official romanization system, Pinyin. Some sounds

are similar to English, but others are otherworldly. For example, how

on earth do you pronounce “Xiamen?”

All Chinese words come in 3 parts: initials, finals, and tone. In “Xiamen,”

“X” is the initial and “ia” the final, and the

“Xia” is pronounced with the 4th tone.

Pinyin’s “X” sounds like “sh,” so Xiamen

is pronounced like “Sh-Yah Men,” (with Sh and Yah crammed

together so that Xiamen has only two syllables-something like “shaman

with a yah after the sh”). (See page 393).

With only 400 or so distinct sounds, Mandarin is a haven for homonyms,

but the 4 tones (plus a 5th "neutral" tone, and context) help

us decipher them:

1st tone is level, and at the top of one’s

normal vocal range for speaking.

2nd tone rises from the middle of one’s

range to the top.

3rd tone starts in the middle, drops to the

bottom, and rises at the end (Susan Marie says that if your chin hits

your chest on the low note, you’ve got it right).

4th tone starts high and ends low, as if

you were scolding someone.

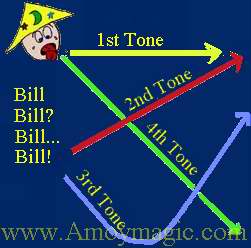

The four tones (sounds like a 60s Pop Group!) sound like the diagram above.

In a tonal language, tones don't simply give an emotional

undertone (anger, fear, joy, surprise) but completely change the meaning

of words. Take ma, for example. With 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th tones, ma

means “mother,” “hemp,” “horse,” and

“to curse.” Get it wrong and you might call someone’s

mother a horse!

Intimidated? Don’t be! And don’t cop out with the “I’m

tone deaf” ploy because you’ve been using tones since you

were a toddler…

Back to Top

“Tone

Deaf...”

...and other Lame Laowai Myths

Frustrated Laowai often excuse their poor Mandarin with,

“I’m tone deaf!” Sheer nonsense. All English speakers

use tones—especially us married ones. I’ve heard all four

of Mandarin’s tones, and a few dozen more, from Susan Marie.

When Susan yells, “Bill!” with the 1st tone, she means, “Come

here!” The 2nd tone “Bill” asks, “Where are you?”

or “Is that you?” The 3rd tone “Bill” is reserved

for giving me the third degree and means, “Do you expect me to swallow

that?” The 4th tone “Bill,” a sharp, barking descent,

means I’m in hot water. But when my sweetheart drops my nickname

altogether and intones with the dead calm of a Taiwan typhoon’s

eye, “William,” it is the neutral 5th tone, a portent of dire

peril, and I am not long for this world.

Americans, particularly us domestipated ones, know tones.

Fortunately, Chinese are a forgiving people, even when

you massacre your Mandarin and create tones of your own. A simple “Ni

Hao Ma” (how are you) will have your congenial hosts exclaiming,

“You have such excellent Chinese!”

But do them and yourself a favor and master PinYin.

Back to Top

Pinyin Initials, Finals, and Approximate English Equivalents

Initials

b,m,m,f,d, about the same dou dough

n,l,g,k,j,s, as in English gan gone

y,ch,sh,t,w shu shoe

c Like ts in rats cai tseye

can tsahn

h Guttural h, like hao how

German ch in ach hu who

q Like ch in chick qu chew

qin cheen

r Between j & r ru roo

x Like sh xia shee-yah

z Like ds sound zai dzye

in kids zong dzong

Back to Top

Pinyin Finals

Pinyin English Examples Pronunciation

a ah in ah! ba bah

ta tah

ai Like y in my lai lye

hai hi

an ahn (lawn) can tsahn

ang ahng (angst) mang mahng

ao ow in cow zao zow

ar ar in are nar nar

e u in bush re ruh

ei a in day gei gay

en un in pun wen wun

eng ung in rung leng lung

er ur in purr mer mur

i Like ee in wee qi chee

(after b,p,m,d,t,n,,j,q,x) mi mee

Like z after z,c,s ci cz

zi dz

Like r after ch, shi shir

sh, and r chi chir (chirp)

ia ee-ya, in one syllable xia sheeyah

ian yen tian tyen

iang yahng jiang jyahng

iao ee-yow (meow, piao pee-yow

in one syllable) tiao tee-yow

Pinyin English Examples Pronunciation

ie yeh tie tyeh

in een in preen pin peen

ing ing in sing ming ming

iong eeyong (long o) xiong sheeyong

iu eo in Leo liu leo

o roughly like a mo mwo-uh

long o and short u po pwo-uh

run together, with a w in front

ong Like ong in gong, tong tong

but with long O sound.

ou o in toe zhou joe

u like oo in boo, except du doo

after j,q,x,y, and then lu loo

like the French eu yu yeu

ua wah (ua in guava) gua gwah

uai wye (as in rye) guai gwye

uan wahn (swan) except duan dwahn

after j,q,x or y, when

it is wen (when) yuan ywen

uang wahng (as in angst) kuang kwahng

ue oo and yeh (yeah) said xue shooeh

in one syllable

ui like way chui chway

un like woon with the jun jwun

oo of book

uo like o (oh) and u (uh) duo dwo-uh

in one syllable

![]() Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites ![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album ![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides ![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn ![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn. ![]() Roundhouses

Roundhouses

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Jiangxi

Jiangxi

![]() Guilin

Guilin

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books

![]() Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY

LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]()

![]() Temples

Temples![]()

![]() Mosque

Mosque

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top