![]() Click

to

Access

Click

to

Access

OUTSIDE China

![]() Click

to Access

Click

to Access

INSIDE

China ![]()

TRAVEL LINKS

![]() Xiamen

Xiamen

![]() Gulangyu

Gulangyu

![]() Jimei

Jimei

![]() Tong'an

Tong'an

![]() Jinmen

Jinmen

![]() Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

![]() Quanzhou

Quanzhou

![]() Wuyi

Wuyi

![]() #1Fujian

Sites!

#1Fujian

Sites!

![]() Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album

![]() Books

on Fujian

Books

on Fujian

![]() Readers'Letters

Readers'Letters

![]() Ningde

Ningde

![]() Zhouning

Zhouning

![]() Longyan

Longyan

![]() Sanming

Sanming

![]() Putian

Putian

![]() Bridges

Bridges

![]() Travel

Info,

Travel

Info,

![]() Hakka

Roundhouses

Hakka

Roundhouses

![]() Travel

Agents

Travel

Agents

MISC. LINKS

![]() Amoy

People!

Amoy

People! ![]()

![]() Darwin

Driving

Darwin

Driving ![]()

![]() Amoy

Tigers

Amoy

Tigers

![]() Chinese

Inventions

Chinese

Inventions

![]() Tibet

in 80 Days!

Tibet

in 80 Days!![]()

![]() Dethroned!

Dethroned!

![]()

![]() Misc.Writings

Misc.Writings

![]() Latest

News

Latest

News

![]() Lord

of Opium

Lord

of Opium

![]() Back

to Main Page

Back

to Main Page

![]() Order

Books

Order

Books![]() Xiamenguide

Forum

Xiamenguide

Forum

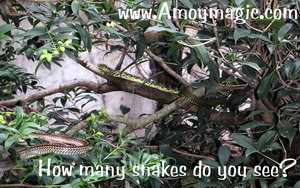

| King

Cobras Square Bamboo! |

Wheel- barrow Wisdom! |

Tao of Tea! | Wuyi Nature Preservation Area | Xiamei Village -- Poker Faces and Blacksmiths |

bras

were facing off in the clearing, hoods flared, fangs bared, tongues darting.

Slowly, he pointed his camera at them. “Flash!” Both

serpents turned towards Wu Guangmin. “I couldn’t outrun them,”

he said, “So I took another photo. The flash scared them. They fled

one way and I fled the other!”

bras

were facing off in the clearing, hoods flared, fangs bared, tongues darting.

Slowly, he pointed his camera at them. “Flash!” Both

serpents turned towards Wu Guangmin. “I couldn’t outrun them,”

he said, “So I took another photo. The flash scared them. They fled

one way and I fled the other!”

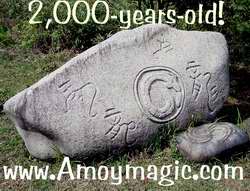

If

Min is the Snake Kingdom of China, Wuyi claims to be the “Snake

Kingdom of the World.” As this 2,000-year-old stone shows,

ancient Min worshipped snakes. And some temples are dedicated to serpent

worship even today.

If

Min is the Snake Kingdom of China, Wuyi claims to be the “Snake

Kingdom of the World.” As this 2,000-year-old stone shows,

ancient Min worshipped snakes. And some temples are dedicated to serpent

worship even today.

In spite of the king cobras, bamboo vipers, and 33-foot

pythons,  Wu

Guangming spends evenings and weekends traipsing about Wuyi Mountain.

Since the late 1700s, European, American and Japanese naturalists have

delighted in its biological diversity, which probably rivals Eden itself.

Fully 92% of Wuyi is forested, and at last count (though I wonder who

on earth counted?), Wuyi boasted 2,466 higher plant species, 840 lower

plant species, 475 vertebrate species, 100 species of mammals, 300 species

of birds, and 31 insect orders with 4,557 species (half of which we had

in our Xiamen University apartment before we screened in the windows).

Wu

Guangming spends evenings and weekends traipsing about Wuyi Mountain.

Since the late 1700s, European, American and Japanese naturalists have

delighted in its biological diversity, which probably rivals Eden itself.

Fully 92% of Wuyi is forested, and at last count (though I wonder who

on earth counted?), Wuyi boasted 2,466 higher plant species, 840 lower

plant species, 475 vertebrate species, 100 species of mammals, 300 species

of birds, and 31 insect orders with 4,557 species (half of which we had

in our Xiamen University apartment before we screened in the windows).

Back to top

Square

Bamboo Bamboo lovers delight in Wuyi’s

80+ bamboo groves, which have 1/3 of the Chinese species of bamboo—including

the exotic, black-skinned square bamboo (Fangzhu). Square bamboo was immortalized

by the ancient poet Guo Mou Ruo in a poem that you can find proudly printed

on “Wuyishan Cigarette” packs. And as a Wuyi native said,

“Square bamboo is great to eat!” (Makes a good square meal,

I bet!)

(By the way--you can also find square bamboo in Northeast Fujian's Taimu

Mountain, in Ningde).Back to top

Wu Guangmin is bent on capturing old China

on film before it vanishes. He said, “ In

another decade you won’t see farmers with plow and oxen, or 3-wheeled

homemade tractors, or grannies with bound feet. And the beautiful architecture

is vanishing—hauled away by antique dealers from Shanghai and Xiamen.

In a few decades all we’ll have is photos.”

In

another decade you won’t see farmers with plow and oxen, or 3-wheeled

homemade tractors, or grannies with bound feet. And the beautiful architecture

is vanishing—hauled away by antique dealers from Shanghai and Xiamen.

In a few decades all we’ll have is photos.”

Armed with black and white film for architecture and color for people

and scenery, Wu Guangmin averages ten rolls of film per day, from which

he may get 3 or 4 acceptable photos. Endless photography is accompanied

by endless questions. “Why did the artists use a dragon theme here,

a phoenix there, a Chinese unicorn between them?” He has published

an entire book on nothing but ancient architecture, with shots of everything

from carved window frames and stone lintels to bed posts.

A friend in his hometown of Jian’ou hooked Guangmin on photography

in 1993. He moved to Nanping’s MinBei Daily in 1996, and since moving

to the Wuyi Shan Daily in ‘98, Guangmin has photographed premiers,

presidents, and queens, but his heart is still in culture, tradition—and

nature.

Back to top

Wuyi Welcomes

UNESCO The 60 sq. km. Wuyi National

Scenic Spot, 15 km south of Wuyi City, is best when spring rains create

countless waterfalls coursing through the rich semi-tropical foliage.

And if you book in advance you need never fear getting rained out, because

Wuyi officials have guanxi with the man upstairs. One man solemnly informed

me, “It always pours the few days before official functions, but

never fails to clear up the day of the event.” ....

Nine

Bend Stream (Jiuqu Xi) The two-hour rafting excursion

isn’t cheap—80 Yuan a person—but it’s the best

part of Wuyi (besides the climb up Tianyou—Heavenly Tour—Peak).

And you’re actually paying for two rafts strapped together, two

pole-men, the cost of hauling the raft back upstream by truck, and two

hours of nonstop commentary and poetry by men gaily decked out in traditional

blue Chinese jackets and nontraditional bright green plastic boots.

Nine

Bend Stream (Jiuqu Xi) The two-hour rafting excursion

isn’t cheap—80 Yuan a person—but it’s the best

part of Wuyi (besides the climb up Tianyou—Heavenly Tour—Peak).

And you’re actually paying for two rafts strapped together, two

pole-men, the cost of hauling the raft back upstream by truck, and two

hours of nonstop commentary and poetry by men gaily decked out in traditional

blue Chinese jackets and nontraditional bright green plastic boots.

Back to top

Great King Peak

(Da Wang Feng) is at the mouth of the Nine Bend Stream. Given a little

imagination, or a couple of swigs of Chinese rice whisky, it resembles an ancient Chinese official’s hat. On the east

side you can see the Immortal Transformation Cave (Shengzhen Dong). The

great philosopher Zhuxi claimed that King Wuyi once lived in this cave,

but it’s just a hole in the wall.

whisky, it resembles an ancient Chinese official’s hat. On the east

side you can see the Immortal Transformation Cave (Shengzhen Dong). The

great philosopher Zhuxi claimed that King Wuyi once lived in this cave,

but it’s just a hole in the wall.

Jade

Maiden Peak Our poetical pole-man

waxed most lyrical about Wuyi’s most celebrated landmark, Jade Maiden

Peak (Yunu Feng). “She resembles a maiden standing gracefully. The

bare rock is smooth as skin. The grass and shrubbery on top are her hair.

If you gaze at her reflection in the pool below, you’ll see a beautiful,

traditional maid, deep in thought, dreaming of a bright future.”

He’d better lay off the rice whisky! I didn’t think her face

or figure was anything to swoon over, and her hair was a mess. She was

nice for a rock, but I’d never marry her.

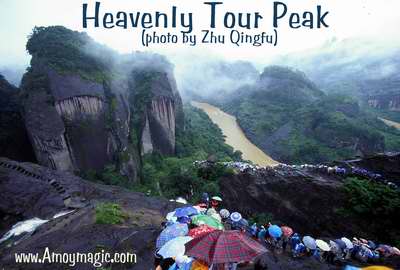

Heavenly

Tour Peak (Tianyou Feng) Wuyi’s best view,

by far, is from Heavenly Tour Peak, which can be seen from the 3rd, 5th,

and 6th bends in the Nine Bend Stream. The path begins at the Tea Plantation

Cave (Chadong) and winds past the Clothes Drying Rock (Shai Bu Yan). Bird’s

Eye Lookout (Yilan Tai) offers a spectacular view of islands of mountains

in a sea of clouds (which Chinese call "The Ends of the Earth")

Heavenly

Tour Peak (Tianyou Feng) Wuyi’s best view,

by far, is from Heavenly Tour Peak, which can be seen from the 3rd, 5th,

and 6th bends in the Nine Bend Stream. The path begins at the Tea Plantation

Cave (Chadong) and winds past the Clothes Drying Rock (Shai Bu Yan). Bird’s

Eye Lookout (Yilan Tai) offers a spectacular view of islands of mountains

in a sea of clouds (which Chinese call "The Ends of the Earth")

Back to top

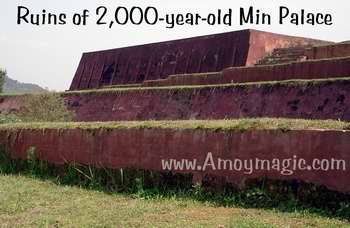

Min Yue Kingdom Museum

(Chengcun Hancheng Yizhi)

About 35 km south of Wuyi City, south of the 101 highway’s 341 km

marker and the railroad track, lies the 2,000-year-old ruins of the  Minyue

King’s palace.

Minyue

King’s palace.

The 10,000 sq. m palace foundation rises like a lopped off Mayan temple.

It once boasted south-facing palatial buildings, east and west gates,

side gates, east and west wing rooms, and a 10m x 5m bathing pool.

Minyue Well

My companions used the 2,000-year-old well to refill their water bottles.

“The water is still pure, Professor Pan, and cures many illnesses!”

But I wondered how pure it could be with a constant stream of tourists.

Only minutes ago an unfortunate fellow had dropped his eyeglasses down

the well, and who knows what had preceded it.

Today, nothing remains of the ancient Min splendor but the great foundation,

a few reconstructed walls, outlines of the rooms’ foundations, and

a large expanse of grass. Here and there, glass-covered square casements

on the ground allow tourists to see the original baked gray tiles, with

their geometrical designs.

The MinYue Museum, a castle-looking

affair a few hundred meters south of the ruins, has a large mural of peasants

adoring the skirted MinYue King, a statue of the mighty man, and some

excavated pottery to shed light on how the kingdom went to pot.

It’s worth a stop, but even more fascinating is

the marvelously preserved Ming Dynasty Village just a couple of kilometers

further up the road, past the ruins...

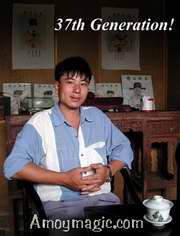

Tea House & Roots Our

first stop was the teahouse opened February, 2001, in a house built in

1620. The proud young proprietor, Mr. Zhao Shan Zhong, showed us his Ancestral

Records book, and boasted that he was the 37th generation of the line

in the middle. He asked about my own roots and was surprised to learn

that I had no idea who my great, great grandfather was...

The ancient cobble stone path was awkward, but it beat mud. It did have

a narrow six-inch smooth stone path down the middle, monopolized by bicycles

and the ingenious one-wheel wheelbarrows that epitomize Chinese ingenuity

and practicality.

Wheelbarrow

Wisdom It is said General Liang

invented  wheelbarrows

about 1800 years ago. With the center of gravity over the one immense

wheel, the user has only to balance and steer the “wooden ox”—unlike

western wheelbarrows, in which the user must heft much of the load.

wheelbarrows

about 1800 years ago. With the center of gravity over the one immense

wheel, the user has only to balance and steer the “wooden ox”—unlike

western wheelbarrows, in which the user must heft much of the load.

The imminently practical Chinese wheelbarrow transported

everything from produce to people, and with only one wheel, the wooden

ox easily navigated the rice paddies’ narrow dikes that were South

China’s only roads well into the 20th century. Back

to top

Nitpicking Tea Pickers A

couple dozen people in an old courtyard

were sorting tea leaves. I vowed I’d never again take tea for granted.

It is an amazingly tedious job, sorting and selecting the tiniest, most

perfect leaves, and tossing the stems. It’s hard to imagine tea

can be so cheap, given the labor behind one pot of the stuff.

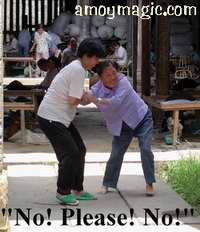

While I shot photos, two of the ladies began yelling at one another in

the local dialect. Finally, the taller lady dragged the smaller one outside

the house, to box her ears I  suspected…

suspected…

After more fierce arguing, she ran inside and grabbed her victim’s plastic flip flops and hand fan, wrestled with her some more, and finally grabbed her by the back of her shirt and led her, triumphantly, down the street. To the judge? To jail? Wu Guangmin laughed as he explained. “She was simply inviting her next-door neighbor to lunch! Chinese keqi (ceremonial politeness) of course requires her to refuse at least 2 or 3 times—but even I have never seen it carried this far!”

Gucheng

Ferry Behind Gucheng was an old reddish temple

to Mazu, the sea goddess. The granny caretaker invited me in and said,

“Some foreigner left this hat here. Is it yours?” And here

I thought I was blazing new trails....

“Twenty and Seven tally with the doctrine ‘Three times

Nine.’ One will be calm and feel moist in the throat and sweet between

teeth. It’s a great pleasure to travel and drink the famous tea

in the Wuyi Mount.”

...............................................From

Wuyi brochure

The

Tao of Tea When the Dutch Trading

Company first shipped tea from Macao to Europe, back in 1607, they called

the blissful brew “Wuyi,” pronounced just like the noise my

West Virginian uncles make after swigging home brewed white lightning:

Wooyee! Tea doesn’t pack the same punch as that Appalachian ambrosia,

but it does have enough caffeine that ancient Chinese medics prescribed

it for everything from impotence to palsy.

Chinese, especially Fujianese, take tea seriously. A Taiwanese friend

gave me a small canister of tea that set him back $200 US. “Don’t’

waste it on me!” I protested. “I can’t tell Coke from

Pepsi, much less $200-a-pound tea from the local fifty-cent variety.”

“You must learn,” he argued, “To savor the bouquet like

a fine wine, and allow a few drops to tantalize the tongue, and enjoy

the bite and the sweetness that follow the swallow.” So he prepared

the elegant Minnan Tea Ceremony, which is the father of the elaborate

Japanese version, but simpler. While Chinese seem to “stand on ceremony”

regarding all else in life, they never allow ritual to spoil their enjoyment

of fine food or tea (or women, judging from their 1.3 billion population).

My friend proffered, with two hands of course, the tiny Minnan teacup,

which is little more than a clay thimble, and frustratingly inefficient

for someone used to Super Big Gulps and two-handed German steins. I sniffed

it dutifully, then downed the cup and smacked my lips. “Good stuff,”

I said. My Taiwanese friend sighed in resignation, and probably regretted

the waste of good tea on his barbarian friend. But it was not wasted.

I served it later to my Chinese guests, who reveled in it.

Back to top

The

Tea is Within You! Near the large stone statue of Maitreya

(Milofu) is the Heavenly Heart Eternal Happiness Meditation Temple (Tianxin

Yongle Chansi), Wuyi’s largest Buddhist complex. It was built about

879 A.D. on one of Chinese Buddhism’s eight holiest mountains. The

temple’s Abbot expounded for me the spiritual ramifications of tea

tasting.

The

Tea is Within You! Near the large stone statue of Maitreya

(Milofu) is the Heavenly Heart Eternal Happiness Meditation Temple (Tianxin

Yongle Chansi), Wuyi’s largest Buddhist complex. It was built about

879 A.D. on one of Chinese Buddhism’s eight holiest mountains. The

temple’s Abbot expounded for me the spiritual ramifications of tea

tasting.

His overview of Buddhism was obviously tailored to his barbarian audience.

He said Guanyin has a master’s degree and Buddha a Ph.D., but that

no one has yet reached the post doctorate pinnacle of enlightenment.

As the Abbott brewed his beverage he explained, “Some people can’t

tell good tea from bad.” Before I couldvolunteer myself for that

category he added, “That’s because those people have nothing

spiritual about them. A taste for tea cannot be taught or learned. It

is in one’s heart.”

I wonder how the Abbott would fare spiritually at Starbucks? ...

Back to top

One Size Fits All  A

dozen vendors hawking carved stones, glass-cum-crystal necklaces, and

miniature bamboo rafts and palm fiber capes besieged us as. We haggled

over a mini raft and rain cape, and the granny exclaimed, “You’re

great at bargaining! Ok, I’m losing money on this sale—but

for the foreign friend…” They turned out to be half the price

in town.

A

dozen vendors hawking carved stones, glass-cum-crystal necklaces, and

miniature bamboo rafts and palm fiber capes besieged us as. We haggled

over a mini raft and rain cape, and the granny exclaimed, “You’re

great at bargaining! Ok, I’m losing money on this sale—but

for the foreign friend…” They turned out to be half the price

in town.

No one dickers like the Chinese. Years ago in Longyan, Sue told a street

vendor that a sweater was too small. The lady replied, "Bu yao

jin! (No problem!) They stretch when you wear them!”

“I don’t know…” Sue said. She tried another but

it was too large.

“Bu yao jin!” the granny said. “They shrink

when you wash them!”

Tea’s

Holy of Holies After the gatekeeper ripped our

tickets in half and handed us the stubs, we made our way up a narrow stone

path winding beside a cold creek that meandered between narrow blackened

cliffs covered with moss, ferns and wild azaleas. Little striped fish,

like clown loaches, frolicked in the icy creek.

Wuyi’s climate, the rich nutrients in the soil, the narrowness and

direction of the valley (strong sun at noon, weak the rest of the day),

and the high humidity from the continual runoff have created the perfect

environment for growing Fujian’s finest tea.

If you aren't into hiking through surrealistic scenery, you can pretend

to be a Mandarin and be borne by quaintly clad Chinese on a colorful litter.

They don’t provide cymbals and shouting attendants cracking whips

to clear the path ahead, though I suppose you could pay extra for it....

Big Red Robe

We crossed the creek on small stones, passed a small Chinese pavilion

(for small Chinese tourists?), and entered an ancient gate that warned,

“No Smoking!” because the three bushes within are the planet’s

sole source of Big Red Robe tea, and irreplaceable.

Many legends explain the origin of the name “Red Robe.” One

claims that monkeys helped the kind monks of Tianxin temple to pick the

best leaves from the highest branches. The Emperor owned the monkeys,

so they wore red robes, and clamoring through the tea bushes they resembled

bright red flowers. Another legend claims an imperial official sent to

supervise tea picking hung his red robe in the tree and joined in the

picking himself.

The three Big Red Robe bushes originally grew wild on top of the mountain,

but centuries ago slid halfway down and have clung there since. All other

Red Robe bushes descend from these three, and are called Little Red Robe.

Big Red Robe bushes are never watered, so the flavor varies year to year,

depending upon the mineral content and the weather. The flavor is flowery

some years and milky others. Little Red Robe tea, I was told, almost always

has a somewhat milky flavor—though the flavor improves as the bushes

age (and the higher the elevation, the better the flavor).

Since less than a pound of Big Red Robe is grown annually, it is usually

reserved for Big Red Bigwigs, at the 2nd Canton Tea Fair in 2002, a mere

20 grams of this most famous of Oolong teas was auctione-for 180,000 Yuan!

That’s more than we spent on Toy Ota! (That’s a bit over 400,000

USD a pound.) I’ll probably never taste Big Red Robe, and I wouldn’t

appreciate it if I did, but Wu Guangmin did give me some Shuixian Hong

Cha (Narcissus Black Tea). “It’s very rare,” he said.

“It is grown in the nature preserve, and only 20 pounds were picked

this year. It was roasted with wood, not coal, with a layer of stone over

that, so it preserves the taste of stone and wood.” That was the

second time someone had raved about the flavor of wood and stone. I wonder

if Chinese ever make stone soup?

Later, Wu Guangmin brewed up a pot of Narcissus Black Tea, and I sniffed

the bouquet, and rolled it around my tongue, and sipped slowly from the

Minnan tea thimble. It still tasted the same to me as the 50 cent stuff--but

I’ll never tell that to the Buddhist Abbott.

Back to top

Water

Curtain Falls (Shuilian Dong) Our guide gave Shannon and

Matthew bottles of mineral water and said, “Refill them from any

spring along the road. They’re all pure!” Then she asked,

“Anyone need to sing a song?” Karaoke in the mountains?! It

turned out this was a local euphemism for going to the bathroom—so

I sang several stanzas.

Water

Curtain Falls (Shuilian Dong) Our guide gave Shannon and

Matthew bottles of mineral water and said, “Refill them from any

spring along the road. They’re all pure!” Then she asked,

“Anyone need to sing a song?” Karaoke in the mountains?! It

turned out this was a local euphemism for going to the bathroom—so

I sang several stanzas.

An elderly couple at the Water Curtain Falls’ base charged two Yuan

for photos with their pigeons. The granny placed corn in the boys’

hands, blew her whistle, and the birds shot into the air, flying about

madly like the birthday party scene from Hitchcock’s “The

Birds.” It took several whistles to get a photo with a bird in each

hand, and I was bushed, but a bird in each hand is better than twenty

in the bush.

The so-called Water Curtain looked more like runoff from a gigantic leaky

faucet than a curtain, but the sheer granite cliff, the pond, and the

tropical plants gave the frail falls an exotic setting.

The Hall of Three Sages,

who in their day dispensed thymely advice, is halfway up the trail to

the right of the pond, was built in 1147 as a memorial hall for Master

Pingshan, and renovated in 1923. Folk from all over Fujian flock here

to pay homage to Liuzihui (1101-1147), Liufu (?-1181, student of Liuzihui),

and Zhuxi, who founded Neo-Confucianism in his “Wuyi Institute.”

Wuyi

Nature Preservation Area The following morning

we headed for the Wuyi Nature Museum on lofty Huanggan Mountain. A bus

makes the trip daily from Wuyi’s Short Distance Bus Station (Duantu

Chiche Zhan), and several buses a day go to the lower areas. Laowai need

passports to enter, as this is a UNESCO preservation area.

The road was so bumpy I had to clutch the seat in front with both hands.

I finally said, “I’m moving to the front of the bus.”

“Good idea,” the driver said. “The bad road’s

coming up.”

The museum’s vast display of stuffed animals, birds, reptiles, and

mounted insects more than made up for my disappointment. Tourists remarked,

“Oh yes, this one is good to eat. That one is too. But that one

is so expensive—$2000 yuan each!”

Back to top

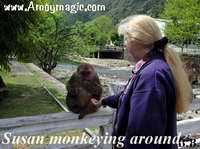

Monkey

Business The monkeys heard our bus approach and raced

down the mountainsides to the parking lot to snatch tourists’ peanuts.

One man saved his entire breakfast for the simians: fried eggs, tofu,

fruit, and pickled vegetables. But they wouldn’t touch a bit of

it. Maybe he should have offered them chopsticks as well...

Monkey

Business The monkeys heard our bus approach and raced

down the mountainsides to the parking lot to snatch tourists’ peanuts.

One man saved his entire breakfast for the simians: fried eggs, tofu,

fruit, and pickled vegetables. But they wouldn’t touch a bit of

it. Maybe he should have offered them chopsticks as well...

Worker Exploitation

A few years back it was reported that a tiny 7-ounce mouse-sized Chinese

monkey had been rediscovered in Wuyi Mountains. A 12th century Chinese

scholar supposedly trained these miniature monkeys to prepare ink, pass

brushes, and turn pages. But it was sheer exploitation of labor, because

the monkeys slept in tiny pots and worked for peanuts.

Animal Rescue Restaurant The

Animal Rescue Center, just up the road from the Museum of Natural History

and across a small wooden bridge, housed a peacock and a few other small

creatures, including a blind bear and a bear missing a paw. Maybe the

paw went to the restaurant across the lawn, where we had a lunch of wild

veggies and creatures. So many tourists exclaimed, “Wah! Those are

good to eat!” that I wondered if the Rescue Center wasn’t

a joint venture with the restaurant, but the restaurant manager assured

me, not without a touch of regret, I think, “No protected species

on our menu!”

YulingTing Song Dynasty

Dragon Kiln Just west of Wuyi, two long narrow buildings

snake up facing hillsides like dragons—which in fact they were built

to resemble. Dragon kilns originated in south China about 2,000 years

ago, and this site is all that remains of two of the Song Dynasty’s

longest dragon kilns (2m by 113m). Shards of Song Dynasty porcelain and

pottery molds are so numerous that locals use them to build field walls.

The extinct dragons lie with heads at the base of the hill and tails at

the top. Each kiln had a fire bore, kiln house, and smoke outlet, and

could produce about 80,000 porcelain pieces at a shot. The wares were

fired at 1100? to 1200? for forty hours or so, and cooled for another

24 before they could be taken out to produce the exotic gold-accented

black-glazed porcelain so prized by the Japanese and Koreans.

Potters A

potter demonstrated his craft outside the Ceramic Café, which is

by the pond and the wooden waterwheel. He had two electric potter’s

wheels, but the power was out that day, so he tried his hand at the stone

potter’s wheel, which didn’t even have a foot pedal and had

to be spun by hand.

But every time he’d spin the wheel with one hand, the other hand

would knock his creation out of round, and after scrapping the piece three

times he finally gave up, explaining, “I’m used to the electric

wheel.”

He should have fired it anyway, and sold it to Americans

who think ‘handmade pottery’ necessarily implies misshapen

mugs with big handles and designs painted by a child who has yet to finish

his first coloring book.

Back to top

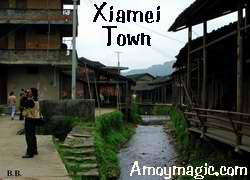

Xiamei

Village Some of Wu Guangmin’s most prized black

and white photos of classic Chinese architecture were taken in the farming

village of Xiamei, 13 km east of Wuyi City on the road to Wufu (which

means “Five Husbands”). But Guangmin was as shocked as I when

a Xiamei farmer at the village gate demanded, “20 Yuan admission—each!”

Xiamei

Village Some of Wu Guangmin’s most prized black

and white photos of classic Chinese architecture were taken in the farming

village of Xiamei, 13 km east of Wuyi City on the road to Wufu (which

means “Five Husbands”). But Guangmin was as shocked as I when

a Xiamei farmer at the village gate demanded, “20 Yuan admission—each!”

Wu Guangming flashed his Press pass but the man said, “I don’t

care. Everyone pays 20 Yuan to enter.”

“I’ve been here many times!” Mr. Wu protested. “My

articles and photos put Xiamei on the map!” And Mr. Wu and his wife

strode past the angry farmer with my sons and I in tow. What a contrast

from the usual, “Come in! Have some tea!” Guangming was embarrassed,

and apologized. “This is rare. People here aren’t like that.”

And he was right. Except for one granny who yelled, “No ticket,

no photos!” the rest of the village treated us like long lost relatives

divvying up the inheritance.

Bony is Beautiful?

One ancient courtyard had a board displaying news articles and photos

that Wu had taken about women with bound feet. “It was a horrible

practice,” a man said.

“True—but we bound women’s entire bodies with corsets,”

I said.

“At least that’s behind us now,” he said.

“True,” I agreed. “Nowadays bony is beautiful and women

voluntarily starve themselves for fashion.”

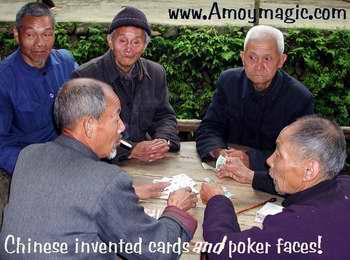

Poker Faces and Blacksmiths Half a dozen grandpas playing poker were proof positive that Chinese invented not only playing cards but also the poker face. What expressions! Not even the foreigner snapping photos broke their concentration!

Just opposite the poker game were two blacksmiths, husband

and wife, hammering away at red-hot steel. “I do it the same way

as my forefathers before me,” the man said proudly.

He was bearded and wiry, but strong, but his wife wielded the bigger hammer

of the two (though she wasn’t bearded). They proudly let me photograph

them at work, even suggesting various poses, and stoking up the flames

for better effect. And they didn’t charge me 20 Yuan for it.

He was bearded and wiry, but strong, but his wife wielded the bigger hammer

of the two (though she wasn’t bearded). They proudly let me photograph

them at work, even suggesting various poses, and stoking up the flames

for better effect. And they didn’t charge me 20 Yuan for it.

Chinese worked with iron and steel 2000 years before Columbus discovered

America. By 400 B.C. (1600 years before Europeans) they used cast iron

to make everything from tools and weapons to pots, pans, and utensils

(and even a solid cast-iron pagoda, in Luoning, Shandong Province!). By

the second century B.C. they’d figured out how to make steel from

cast iron....

Snake Doctor It’s

no surprise that the Snake Kingdom of Wuyi has a Snake Garden (Dazhu Gang

Sheyuan) boasting over 10,000 snakes within its 6,000 sq. m domain (entrance

fee cheerfully refunded if you’re fatally bitten). It’s also

no surprise that Snake Doctors like Xiamei Village’s Master Wang

are in high demand.

Master Wang’s uncle taught him the ancient Chinese herbal cures

from a dusty old tome, and since Wang is illiterate, he memorized them

by rote. There’s no telling what kind of pharmaceutical treasures

are in the man’s head—though he admits to some close calls

at times. “Sometimes, I have to care for patients 8 or 10 days,

especially if they’ve been bitten by a five stepper or a bamboo

viper. If they’d have gone to the hospital, they’d have probably

died, or at least lost an arm or a leg.”

“People lose arms and legs all the time in American hospitals,”

I said.

“Really?” he asked, in astonishment.

“Really,” I said. “Hospitals cost an arm and a leg.”

Snake Oil For

Chinese, snakes are as much boon as bane, because virtually every part

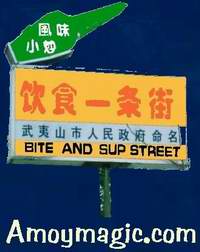

of the snake is considered medicinal, and capable of miraculous cures.

In the Tourist District’s Bite and Sup Street, you can find shops

selling an unimaginable variety of snakes, some pickled in alcohol in

jars of various sizes, and others coiled and dried.

My first intro to snake medicine was in Taiwan, when aborigines milked

a cobra’s venom into a glass of rice whisky and gave it to me to

drink. “Makes you potent!” they said.

“No thanks. Don’t need it,” I said.

“Ohhhh!” They said. But they pressed the issue, and so I drank

it, knowing that it wouldn’t harm me unless I had cuts or ulcers

in my esophagus or stomach. I probably developed ulcers waiting to find

out.

Snake flesh and internal organs all have their uses. The gall bladder

alone can sell for as much as $1,000 US, depending upon the type and size

of the snake. Gall bladders alleviate arthritis pain, and are usually

taken with alcohol, which speeds the snake essence through the body...

Snake penises, soaked in herbs and liquor for 2 to 3 years, are sold for

a small fortune as a Chinese version of Viagra, though more sophisticated

snake experts claim the benefit comes not from the penises but from the

herbs and liquor they’re soaked in.

Back to top

Snake Oil Magical Wine It’s

a wonder there are any snakes left in China, given that this has been

going on for a few thousand (plus 14) years. Back in the Tang Dynasty,

Liu Zong Yuan wrote about the Yi snake ("strange snake"), which

was black, with a white stripe:

“Yishe can recuperate palsy, sprain and swelling, eliminate dead

muscles and kill harmful germs. So imperial physicians began to collect

Yishe twice a year following imperial edicts. People who can catch Yishe

are in great demand, and since they can hand in snakes in lieu of taxes,

many people of Yong Zhou risk their lives to do it.”

Today, a Hunan firm produces “Yishe Magical Wine,” which,

among other things, cures......

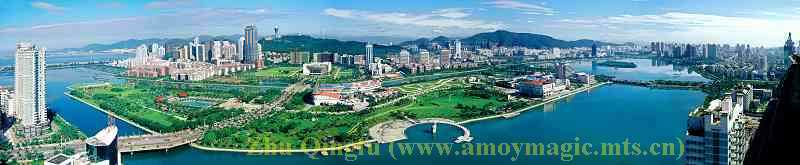

Wuyi City

Sprawling Wuyi City is, on the surface at least, not much different from

thousands of other modern Chinese cities—though there is a marvelous

little street along the riverfront, lined with ramshackle old wooden buildings,

and the 100-meter TuQing wooden covered bridge (circa 1187).

But most of Wuyi’s action is in the newly developed Wuyi National

Tourism and Holiday Area, 11 km south of the city proper (or improper,

late at night). On “Bite And Sup Street,” you can shop and

eat to your heart’s content.

Bite

& Sup Street’s sidewalk restaurants

serve up every dish you can imagine and a few you’d rather not.

Breakfast features tiny pickled onions, sad dried minnows, rice congee,

zongzis (triangular bamboo-wrapped sticky rice with veggies or meat),

deep-fried spring rolls, miniature Chinese steamed buns and dumplings—and

of course the old standby of hot soy milk and youtiao (deep fried dough

sticks).

Bite

& Sup Street’s sidewalk restaurants

serve up every dish you can imagine and a few you’d rather not.

Breakfast features tiny pickled onions, sad dried minnows, rice congee,

zongzis (triangular bamboo-wrapped sticky rice with veggies or meat),

deep-fried spring rolls, miniature Chinese steamed buns and dumplings—and

of course the old standby of hot soy milk and youtiao (deep fried dough

sticks).

Bite and Sup Street is best in the cool of the evening when the brightly

illuminated stalls showcase colorful displays of vegetables, fruits, and

assorted carcasses—some of which are still alive and kicking in

cages and aquariums.

Rabbit, pheasant, miniature mountain deer, king cobra—Bite and Sup

Street is Wuyi’s best zoo. My favorites included the wild mountain

veggies, mushrooms and fungi, and the sweet ‘n sour potatoes, though

the tofu and snails weren’t bad either. One exquisite treat you

can’t miss: Tempura Tea! These are delicate little

Rougui Tea leaves, battered and deep fried. Only in Wuyi can you have

your tea and eat it too!

Wuyi Handicrafts—the Best

Buys in Fujian The shops around Bite and

Sup Street offer the best bargains in Fujian on teas, mushrooms, funguses,

and Chinese handicrafts. The locally made wood, bamboo, and snakeskin

products go for 3 times the price even in neighboring Sanming.

Our favorites include the wooden Chinese puzzle boxes

with their secret compartments, and the miniature reproductions of Fujian

farmers’ hand woven palm fiber capes and hats (which take a couple

of days to make and are rapidly giving way to lighter but stifling plastic

raincoats).

Antique Alley An

abundance of extinguished forebears makes for a bustling antique business

in Wuyi. Dealers from all over China come here to buy ancient pottery

and carved wooden lattices, which they resell at several times the price

in Fuzhou, Xiamen, and Shanghai.

Wu Guangmin introduced me to Mr. Zhou Gao Ying, one of the few art dealers

he trusted. Mr. Zhou had sold antiques out of his home for ten years,

parlaying his profits until he was able to open Gu Yue Xuan. He showed

me some marvelous Tang and Song Dynasty wares, and when I asked how to

tell the real from the fakes, he admitted, “It’s hard to tell.

But these came from local graves, so I know.”

A grave undertaking, to be sure—but the only reliable way of insuring

you’re getting the Real McCoy and not a clever copy. Even then,

caveat emptor. Back in 1932, a Fuzhou Laowai, Malcolm Farley, warned the

wannabe antique collector:

“Since about five years [1927] ago the demands of the museums of

the West and Japan ever increasing for these wares and the supply diminishing

somewhat, certain potters in the north, notably in Honan set out to meet

this demand artificially and have succeeded so well in doing so that now

when even a collector of some acumen buys one of these Han and Tang pieces

he is not sure of whether he is getting one a thousand or two thousand

years old or one made within the past five years or two months. I mean

this literally. The reproductions are so perfect, so well done as to deceive

the expert often and it is hardly to be doubted that almost any museum

may possess some fakes along side of genuine specimens in their cases.”

Back to top

Wuyi Mountain Villa Wuyishan

City has 18 travel agencies, over 130 hotels, and 10,000 beds, so plenty

of room and board. Literally, because the beds are generally about as

soft as a board. My favorite hangout is where the Queen of the Netherlands

stayed: the Wuyishan Villa (Wuyishan ShanZhuang), which has been included

in a book on the world’s best architecture. Great rooms, excellent

food, and some of the best service we’ve seen in China. Try it!

But like the Queen of the Netherlands, you’ll have to go Dutch.

Homeward Bound Our Wuyi

sojourn ended, we bade many new friends farewell and piled into Toy Ota

for the trip home.

Just out of town, and just beyond the “Toll—Run Slowly!”

sign, a flock of ducks blocked the road.

“How many ducks you got?” I called out.

“Oh, about five hundred” the duck herder said proudly, as

he swished his pole, slowly, to clear a way for me to pass.

“Bu yao jin!” I yelled back. “No worries, Mate!”

Roots

About the 297.7 kilometer marker we came to a village that specializes

in root sculptures....

Roots

About the 297.7 kilometer marker we came to a village that specializes

in root sculptures....

And on to Sanming.....

TRAVEL

LINKS  Favorite

Fujian Sites

Favorite

Fujian Sites  Fujian

Foto Album

Fujian

Foto Album  Xiamen

Xiamen

Gulangyu

Gulangyu

Fujian

Guides

Fujian

Guides  Quanzhou

Quanzhou

Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou

Longyan

Longyan

Wuyi

Mtn

Wuyi

Mtn  Ningde

Ningde

Putian

Putian

Sanming

Sanming

Zhouning

Zhouning

Taimu

Mtn.

Taimu

Mtn.  Roundhouses

Roundhouses

Bridges

Bridges

Jiangxi

Jiangxi

Guilin

Guilin

Order

Books

Order

Books

Readers'

Letters

Readers'

Letters

Last Updated: May 2007

![]()

DAILY

LINKS

![]() FAQs

Questions?

FAQs

Questions?

![]() Real

Estate

Real

Estate

![]() Shopping

Shopping

![]() Maps

Maps

![]() Bookstores

Bookstores

![]() Trains

Trains

![]() Busses

Busses

![]() Car

Rental

Car

Rental

![]() Hotels

Hotels

![]() News

(CT)

News

(CT)

![]() Medical

& Dental

Medical

& Dental

![]() YMCA

Volunteer!

YMCA

Volunteer! ![]()

![]() XICF

Fellowship

XICF

Fellowship

![]() Churches

Churches

![]()

![]()

![]() Temples

Temples![]()

![]() Mosque

Mosque

![]() Expat

Groups

Expat

Groups

![]() Maids

Maids

![]() Phone

#s

Phone

#s

EDUCATION

![]() Xiamen

University

Xiamen

University

![]() XIS(Int'l

School)

XIS(Int'l

School)

![]() Study

Mandarin

Study

Mandarin

![]() CSP(China

Studies)

CSP(China

Studies)

![]() Library

Library

![]() Museums

Museums

![]() History

History

DINING ![]() Tea

Houses

Tea

Houses

![]() Restaurants

Restaurants

![]() Asian

Asian

![]() Veggie

Veggie

![]() Junk

Food

Junk

Food

![]() Chinese

Chinese

![]() Italian

Italian

![]() International

International![]()

![]() Visas

4 aliens

Visas

4 aliens

RECREATION

![]() Massage!

Massage!

![]() Beaches

Beaches

![]() Fly

Kites

Fly

Kites

![]() Sports

Sports

![]() Boardwalk

Boardwalk

![]() Parks

Parks

![]() Pets

Pets

![]() Birdwatching

Birdwatching

![]() Kung

Fu

Kung

Fu ![]() Hiking

Hiking

![]() Music

Events

Music

Events

![]() Cinema

Cinema

![]() Festival&Culture

Festival&Culture

![]() Humor&

Humor&![]() Fun

Fotos

Fun

Fotos![]()

BUSINESS

![]() Doing

Business

Doing

Business

![]() Jobs!(teach/work)

Jobs!(teach/work)

![]() Hire

Workers

Hire

Workers

![]() Foreign

Companies

Foreign

Companies

![]() CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

CIFIT

(Trade Fair)

![]() MTS(Translation)

MTS(Translation)

![]()

Back to Top